‘Central was like a river. A mighty river like the Amazon or the Nile, or in this case the Congo. And all the streets were tributaries that branched off from this great river.’

— CLIFFORD “KING” SOLOMON, JAZZ MUSICIAN

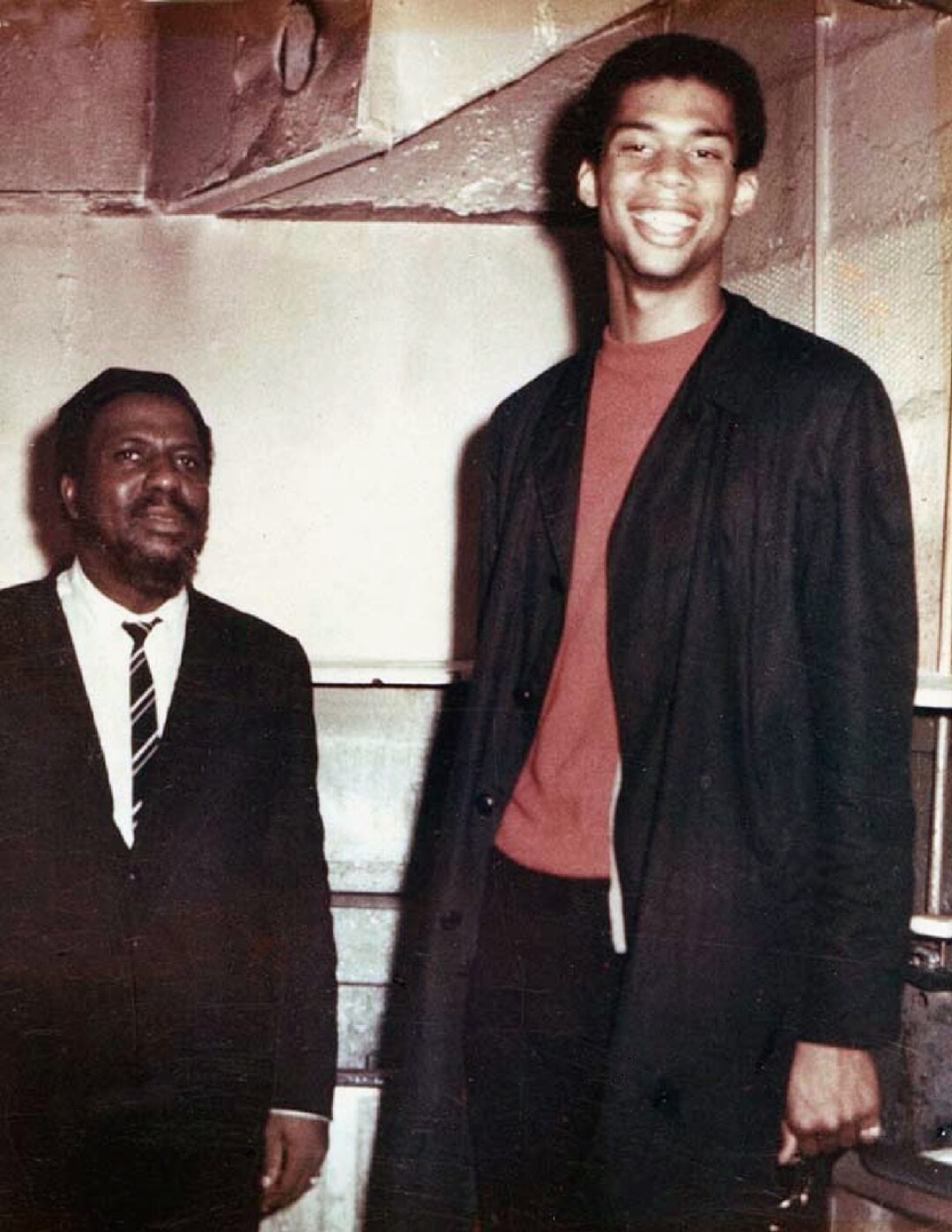

My first exposure to the influence of jazz on Los Angeles was in 1965 when I was a freshman attending UCLA. Edgar Lacey, a junior and fellow player on the basketball team, took me to the It Club to see John Coltrane.

As a teenage jazz enthusiast growing up in New York City, I had listened to all of Coltrane’s records. Jazz was the soundtrack to my life. It was in my blood thanks to my father, who was a transit cop by day, but by night a Juilliard-trained musician who played trombone with many of the jazz greats and introduced me to my childhood heroes, like Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis.

I also had spent a summer in a high school journalism program in Harlem researching and writing about the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, when the greatest African American lions of politics, art, literature and jazz roared loud enough to make Black voices heard around the world. And the world — having never heard Black voices so clear, so engaging, so vibrant — was forever changed because of it. I know I was. Their passion to speak their truths gave me the courage to do the same.

But while my 18-year-old self was sitting with my friends in the swinging It Club, listening to Coltrane’s soulful saxophone seduce the crowd with “Impressions” and “I Want to Talk About You,” I had no idea just how significant jazz was to the history of African Americans in Los Angeles.

In my heart, I was still a child of New York City, an apostle of its rich history, energetic community and vital lifestyle. Although I spent college and most of my NBA career in Los Angeles, it wasn’t until I retired from basketball and began my second career as a writer specializing in African American history and the nuances of popular culture that I learned how one area — Central Avenue — played a vital role in shaping both African American history and American popular culture. It was a revelation — and an inspiration.

But why had it taken me so long to hear about this amazing past that Angelenos should have been bragging about the way they tout their television, movie, and rock music heritage? Why was this particular past, which influenced so much of Los Angeles’ identity, ignored, neglected or buried?

R.J. Smith explained this selective memory in his poetic and incisive book “The Great Black Way: L.A. in the 1940s and the Lost African-American Renaissance”: “Los Angeles is the capital of forgetting. It is a place so fixated on tomorrows or so set on seeming brand-new. … We do the future: until recently we barely accepted we had a past. A past is what many of us came here to escape.”

Hadn’t I done the same thing? Like thousands of star-struck wannabes before me, I had come to Los Angeles to launch my future self, my eyes on the successes and triumphs of a future me. Fifty years later, the future me has come to reflect on the many Black hands of the past that lifted me up to my success — and to honor them.

I became so fascinated with my deep dive into all things Central Avenue that I began developing a noir TV series called “Trouble Man,” set in that district during the late 1940s. (Nothing proves I’ve become a true Californian more than developing a TV series.) It would combine my love of ‘70s-style blaxploitation movies with the ‘40s era’s hard-boiled detectives, the Golden Age of Hollywood, gangsters and, of course, jazz. And a mostly Black cast. The stories would reflect how the post-World War II struggles of Central Avenue gave rise to everything from the civil rights movement to the birth of rock ‘n’ roll. And the soundtrack would be, naturally, jazz.

So, let me be your tour guide through the historic Central Avenue that I came to know, love and revere during many months of research. There’s so much more to see than I could possibly show you on this short trip through time, so I’ll focus on some of the most important sights.

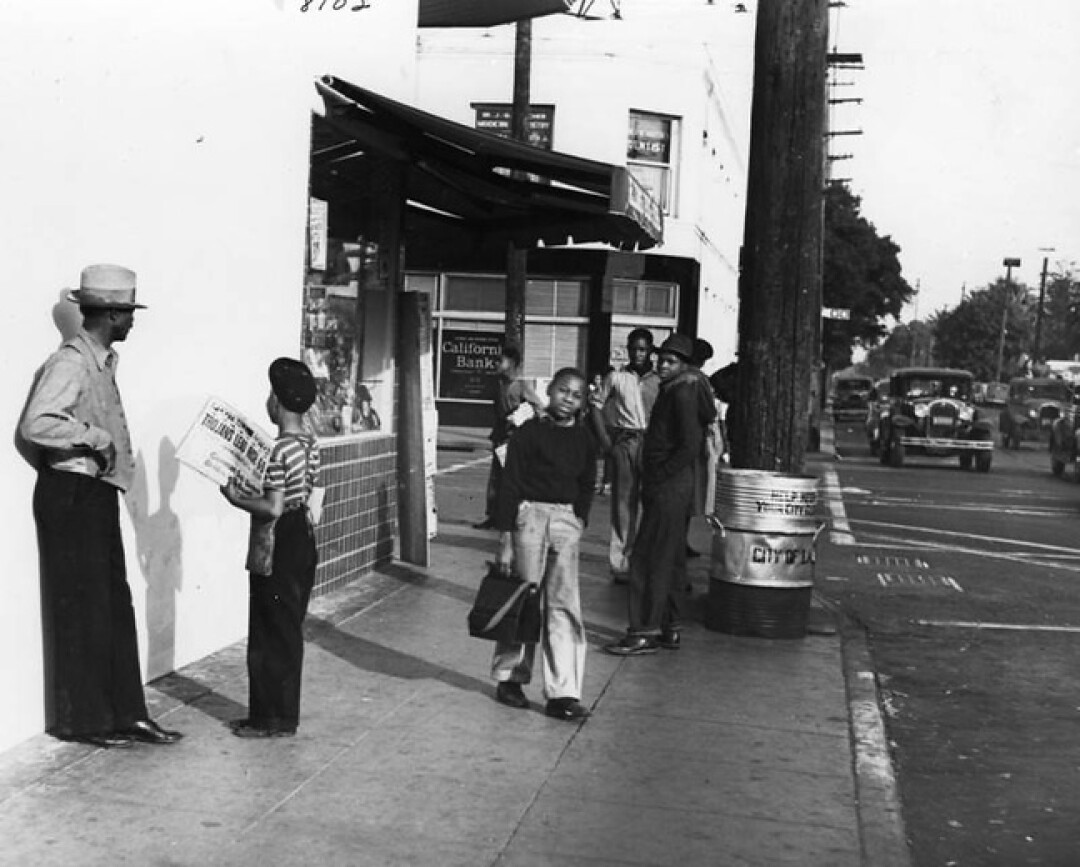

Central Avenue runs north-south like a soldier’s spine through the center of Los Angeles. From the 1920s to the 1950s, these bustling blocks were the thumping heart of the African American community. As in most American cities, informal segregation turned the Black neighborhoods into a city within a city where locals shopped, conducted business, filled prescriptions, got fillings, made last wills and testaments. It was a Black ecosystem where whites ventured only to sample the lively jazz clubs that featured some of the world’s best musicians.

In 1920, at the start of Central Avenue’s rise, the city’s Black population was only 15,579 (3% of the nearly 600,000 people of Los Angeles). The Second Great Migration followed World War II, with thousands of African Americans leaving Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas and Texas to come to California hoping for factory jobs needed to help the war effort.

By 1940, Los Angeles’ Black population had quadrupled to 63,700. In 1950, when Central Avenue’s glorious flame had started to flicker out, Los Angeles had over 4 million people, 217,881 of whom were Black. The 30-year heyday of Central Avenue was, in part, the result of the influx of these hundreds of thousands of new people and their vibrant culture.

White Angelenos first started selling property to Blacks during the Great Depression, when dire economic pressures overcame racism. But whites fought the expansion of the Central Avenue Black community, sometimes with violence, sometimes with laws such as including restrictions in their deeds prohibiting Blacks, Japanese, Mexicans, Indians and Chinese from buying the land. Just as the Black community, whose musical taste in the beginning of the 20th century was conservative, did not welcome the introduction of jazz. But both happened anyway.

Jelly Roll Morton played to full houses between 1917 and 1922 at the Cadillac Cafe on Central Avenue. That brought in celebrities. Said Morton: “We didn’t have anything but movie stars at the Cadillac Cafe as long as I played there.”

Central Avenue thrived. Club Alabam, the Downbeat, the Last Word, the Dunbar Hotel and others hosted the most famous and soon-to-be-famous Black entertainers in the world: Nat King Cole, Lionel Hampton, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Dinah Washington and dozens of others. The avenue became known as “Brown Broadway.” This is what it looked like to a reporter from the California Eagle, California’s largest and most influential Black newspaper:

“Big modern office buildings elbowing tumbledown shacks — Eat shops, in rows — Chicken markets, Chicken markets, Chicken markets — Missions — Speakeasies, black frocked ministers — Flashily dressed furtive-eyed racketeers’ — Ladies of the evening — patrolling in daylight big cars whiz recklessly, cut-outs wide open — colored and white school children arm in arm, no race hatred yet… Second hand stores, gilded emporiums, colored banks — A wonderful colored life insurance building, colored gas stations — A score of colored drug stores … That gives a great visual sense of the street’s lifestyle, but if you really want to feel its kinetic energy, sense of joy and hope, listen to Lionel Hampton’s thumping ‘Central Avenue Breakdown.’”

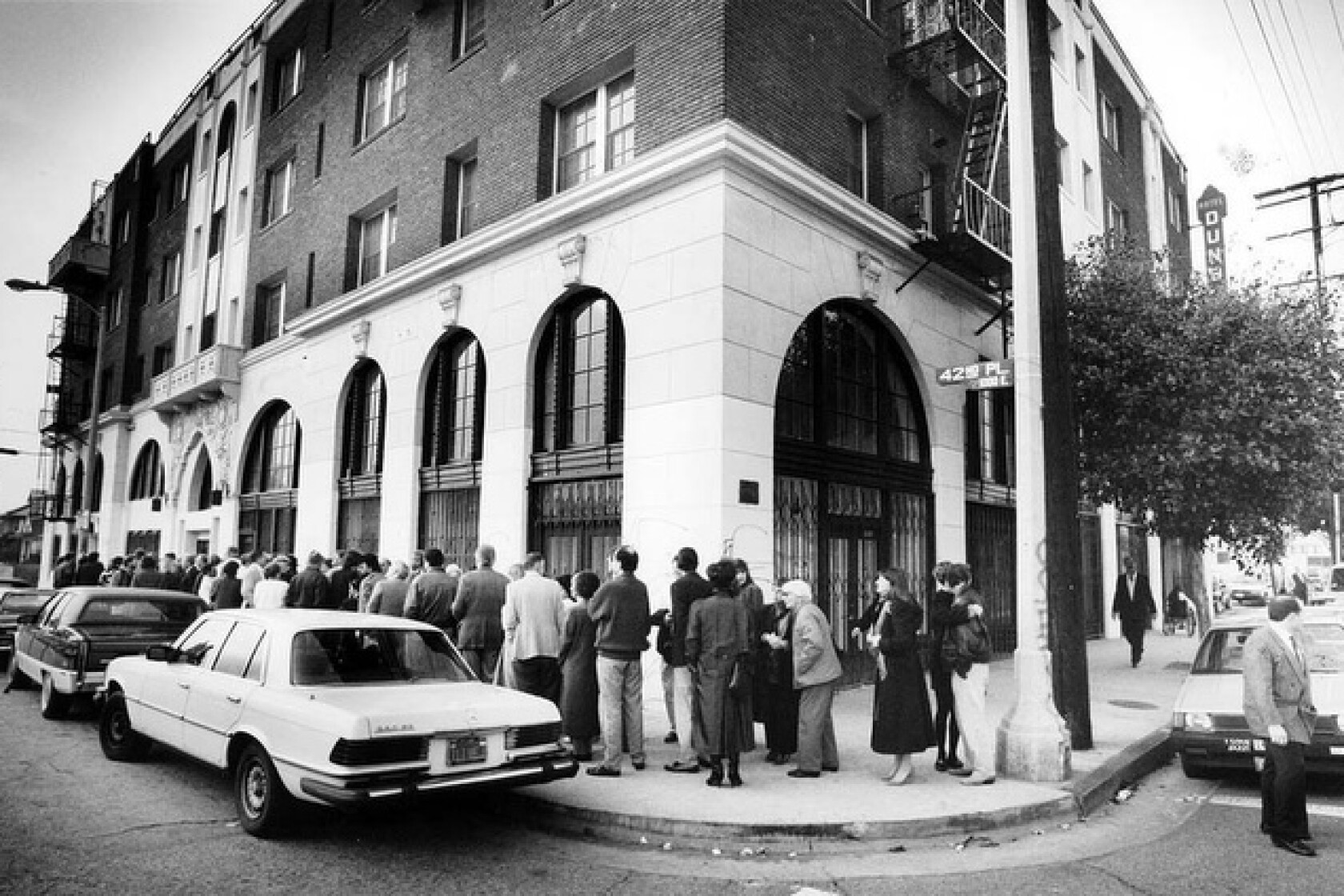

‘It was once the most glorious place on ‘the Avenue.’ At the Dunbar Hotel … you could dance to the sounds of Cab Calloway, laugh till your stomach hurt with Redd Foxx and maybe, just maybe, get a room near Billie Holiday or Duke Ellington.’

— LOS ANGELES HERALD-EXAMINER

Built on the corner of 42nd and Central, the luxurious and elegant four-story, 115-room Dunbar Hotel was a beacon of African American hope. Originally called the Hotel Somerville when it opened in 1928 and constructed exclusively by Black laborers, the hotel was owned by Dr. John Somerville and his wife, Dr. Vada Watson Somerville, the first Black man and Black woman to graduate from USC’s dental school.

Although the Central Avenue community had a large population of middle- and upper-class Black families, there was no first-class hotel in Los Angeles that would cater to Black clients. Hotel Somerville changed that. The hotel was so important to the local community that more than 5,000 people showed up to celebrate its grand opening.

If the People’s Independent Church of Christ (where Hattie McDaniel celebrated her Oscar for “Gone With the Wind” and where Jackie Robinson got married) represented their spiritual aspirations, the Somerville represented their political and social aspirations.

The year it opened, the Somerville hosted the first West Coast convention of the NAACP, featuring W.E.B. Du Bois, the era’s preeminent spokesperson for civil rights. Other Black intellectuals and social justice warriors frequenting the Somerville included poet Langston Hughes and future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Black celebrities, such as entertainer Josephine Baker and boxer Joe Louis, stayed there.

“It was a place where the future of Black America was discussed every night of the week in the lobby,” Los Angeles civil rights activist Celes King III told KCET. “There were very serious discussions between people like W.E.B. Du Bois, doctors, lawyers and educators and other professionals. This was the place where many of them put together plans to improve the lifestyle of their people.”

The Great Depression forced the sale of the Somerville, which was renamed the Dunbar Hotel after Paul Laurence Dunbar, the son of ex-slaves who became an acclaimed poet, essayist and novelist. The hotel building contained many independent businesses, many operated by women, including a flower shop, cafe, barbershop, hair salon and a stenographer’s office.

The Dunbar teemed with celebrity guests and performers: Paul Robeson, Hattie McDaniel, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Fats Waller, Nat King Cole, Lena Horne, Billy Eckstein, Jelly Roll Morton, Ray Charles and Count Basie. Before becoming mayor of Los Angeles, Officer Tom Bradley walked a beat on Central Avenue and often ate at the Dunbar Grill.

“Everybody that was anybody showed up at the Dunbar,” Lionel Hampton told The Times in 1983. “I remember a chauffeur would drive Stepin Fetchit, the movie star, up to the curb in a big Packard and he’d look out the window at all the folks. The Dunbar was also popular with would-be actors because Hollywood directors would regularly stop by the hotel to gather up extras for a day’s work.”

The integration that so many civil rights activists planned for at the tables of the Dunbar was also its downfall. Black celebrities were no longer confined to one hotel and so began staying at other first-class hotels in Hollywood and Beverly Hills. After years of losing money, the hotel closed in 1974.

The recent Eddie Murphy movie “Dolemite Is My Name” chronicles Rudy Ray Moore’s use of the broken-down hotel to film his 1975 blaxploitation movie, “Dolemite.” Today the Dunbar building still stands, though it is now part of a residential community called Dunbar Village.

‘I can see him now walking around with that cigar. When he walked around, you knew he was somebody, OK, because he had that air … which was kind of unusual in those days because being a black man with all that competence that he had, he was like a role model to us.’

— SINGER JEANETTE BAKER TO NPR

When ex-used car salesman John Dolphin arrived from Detroit in 1947, he bought a record store on 40th Street and Central Avenue that exemplified the hustle and creativity of some of the Black entrepreneurs seeking West Coast success. He renamed his store Dolphin’s of Hollywood, despite the fact that Hollywood was miles away; deed restrictions and unwilling sellers prevented Blacks from owning businesses in Hollywood at that time.

“If Negroes can’t go to Hollywood,” Dolphin vowed, “then I’ll bring Hollywood to Negroes.”

Lovin’ John, as he was known, kept the store open 24 hours a day, with a DJ in the storefront window broadcasting on a local radio station, KRKD. Sometimes they would have on-air interviews with stars such as Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday, Little Richard and James Brown.

Determined to promote Black artists at a time when white artists were recording and popularizing Black songs, Dolphin bought air time on white radio stations to broadcast original Black artists such as Sam Cooke and Charles Mingus. The Penguins’ doo-wop hit “Earth Angel” was first released during a live broadcast from Dolphin’s.

Eventually, the store’s success also brought Dolphin unwanted attention. The store was a serious competitor to white record stores. White kids were coming to Dolphin’s, and the authorities, afraid white girls would dance with the Black boys, would blockade the store and on occasion make arrests while sending the white kids home.

Dolphin’s son, Michael, told the Los Angeles Sentinel in 2015 that he recalled police shutting down the store a few times because “there were too many white kids in the store.” But the store always reopened.

Dolphin also started his own recording labels, including Recorded in Hollywood (which he sold to Decca). Dolphin’s slogan was, “We’ll record you today and have you a hit by tonight.”

COLUMN ONE

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

Unfortunately, he also had a reputation for being stingy with paying his artists. That reputation resulted in one of his artists, Percy Ivy, wrongfully thinking Dolphin was holding back royalties. In 1958, Ivy charged into Dolphin’s office and shot him dead.

Dolphin’s of Hollywood closed in 1989.

‘It is a big, well-appointed theater in which all of the actors and almost all of the auditors are negroes. But many white people crowd in, too, because the chance to see negro actors of real ability appearing for their own people rather than appearing as negroes from the white man’s point of view is one that doesn’t come to one in every city.’

— COLUMNIST LEE SHIPPEY, LOS ANGELES TIMES, 1928

The Lincoln Theater was built around 1926, another of the grand movie palaces of the time. It had a stage and orchestra pit, seated 2,100 people and was considered one of the most elegant buildings of the Central Avenue corridor. Because it attracted so many of the same acts as Harlem’s Apollo Theater, the Lincoln became known as the “West Coast Apollo.”

Some of the performers there included Lionel Hampton, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, Fats Domino, B.B. King, Dooley Wilson (Sam in “Casablanca”). These acts attracted Hollywood celebrities such as Charlie Chaplin, Irving Thalberg, Janet Gaynor and Fanny Brice. It was outside the Lincoln that songwriter Eden Ahbez handed his composition “Nature Boy” to Nat King Cole’s road manager. It became one of Cole’s biggest hits.

Black Angelenos outgrew the confines of Central Avenue. The Black businesses helped force integration on a reluctant Los Angeles, and integration gave Black families more opportunities to work and live wherever they chose. There were growing pains, just as there are when any child matures and moves away from his home and childhood community. When he returns years later, he is surprised and a little saddened to see the familiar landmarks closed or replaced. The Watts riots of 1965 had destroyed some buildings and others had fallen to the inexorable tsunami of progress. Dolphin‘s was gone. The Dunbar Hotel was gone. The Lincoln Theater was converted into a church.

The giants of Central Avenue may have gone, but their footprints still remain on all of American culture. The jazz musicians and record promoters also gave birth to rock ‘n’ roll, rhythm and blues, hip-hop and rap. Though Central’s glory days are no more, Los Angeles still celebrates the contributions of so many African Americans that changed the city for the better.

Every year since 1996 (except this year, due to the pandemic), during the last weekend of July, the free Central Avenue Jazz Festival features booths with food, arts and crafts, and community outreach programs. And lots of jazz. It is a joyful tribute to what was and a loving recognition of what we owe. As Dinah Washington sings in Irving Berlin’s “The Song Is Ended”: “The song is ended/But the melody lingers on.”

More Stories

Eric Gales՛s new album 2025, releases single with Buddy Guy & Roosevelt Collier: Video, CD cover

I usually practice with the door open. I always played like that, hoping someone would walk by and discover me: Ahmad Jamal once confessed: Video, Photos

Terry Riley. A landmark reissue of one of the most important figures in 20th-century music: Videos, Photos