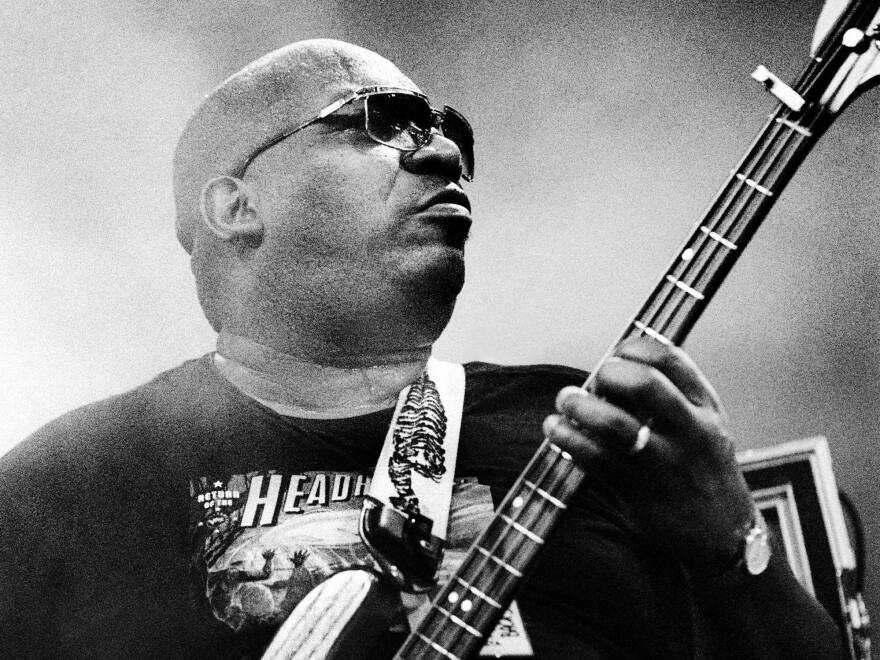

Paul Jackson, who as bassist for Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters helped secure the first million-selling jazz album, died on March 18 in Japan, where he had lived since 1985.

He was 73. His death was confirmed on social media by his longtime musical associate, drummer Mike Clark.

Jackson worked as a sideman with a wide variety of artists, from Santana and the Pointer Sisters to the jazz saxophonists Stanley Turrentine and Sonny Rollins. But he is undeniably best known for his association with Hancock, which lasted through most of the ’70s.

His insistent, conversational electric bass lines propelled Headhunters — with Hancock on keyboards, Bennie Maupin on saxophone, Bill Summers on percussion, and either Clark or Harvey Mason on drums — to the furthest reaches of rapturous jazz-funk. Jackson’s playing both tethered the band to the ground and encouraged it to take flight. He can be heard on all four Headhunters albums under Hancock’s direction: 1973’s Head Hunters, 1974’s Thrust, 1975’s Man-Child, and the 1975 live LP Flood.

The relentlessly funky Head Hunters, inspired more by Sly and the Family Stone than by Hancock’s onetime boss Miles Davis, became the best-selling jazz album of all time on release — cracking the Top 20 on the Billboard album chart. Jackson co-wrote its lead track, “Chameleon.” The band performed on Soul Train, and “Chameleon” became a jazz standard.

“Paul Jackson was an unusual funk bass player, because he never liked to play the same bass line twice, so during improvised solos he responded to what the other guys played,” explained Hancock in his 2014 autobiography, Possibilities. “I thought I’d hired a funk bassist, but as I found out later, he had actually started as an upright jazz bass player.”

Despite his acoustic origins, Jackson’s style on electric bass was fully realized the moment he picked up the instrument.

“It sat in the music room for a long time and then one day he broke it out and started playing exactly as he later would with Herbie upon taking it out of the case!,” Clark told Jazz Journal. “I started playing along and we immediately fell into the funk thing we later got known for. It happened spontaneously and took hold within seconds. Soon we started playing this style with many groups in the Bay Area and became known for this.”

In the mid-’70s, the Headhunters — Hancock’s 1973 album was confusingly title Head Hunters— started performing and recording without Hancock, releasing two albums that became cult favorites among funk fans: 1975’s Survival of the Fittest and 1977’s Straight from the Gate. The stirring “God Make Me Funky,” off Survival of the Fittest, was sampled by everyone from De La Soul to N.W.A. Jackson co-wrote the song and sang lead vocals.

When the Headhunters went to record “Actual Proof,” a notoriously tricky piece, Jackson offered a brand new bass line, one they hadn’t previously used live. Hancock was thrown at first, but also impressed.

“It took me a while, but I figured out a whole different pattern underneath Paul’s bass,” Hancock wrote. “And that’s what we ended up recording. It was a killer bass line, but that’s how Paul was; he could come up with things nobody else could.”

Freddie Redd, a pianist and composer who enjoyed an ascendant hard-bop career in the 1950s and early ’60s, before slipping into semi-obscurity and a resurgence on various local scenes, died early Wednesday morning in New York City. He was 92.

His grandson Leslie Clarke announced his death on Facebook, without stating a cause.

Redd is best known, in and beyond the jazz community, for composing the score to The Connection, a Jack Gelber play produced Off Broadway in 1959. Later adapted for a film by Shirley Clarke, The Connection paints an unvarnished portrait of heroin addicts waiting for their next fix. Redd and alto saxophonist Jackie McLean appeared in the stage production and the film, as well as the soundtrack. Among its enduring Redd compositions is “Who Killed Cock Robin?” (which can be heard in this trailer).

Writing in the New York Times in 1989, Peter Watrous noted that Shades of Redd struck a somewhat traditional chord in the era of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. “But the album is so accomplished and satisfying,” he adds, “that it proves that a genre — in this case hard-bop — can still be fertile long after its historical moment has passed.”

The example Watrous provides is Redd’s opening track, “The Thespian.” It’s no less evident on a subtly intricate shuffle titled “Melanie.”

Redd served in the Army during the Korean War, and while abroad he got his first taste of bebop — Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie’s Shaw ‘Nuff — and was instantly hooked. He returned to New York on his discharge in 1949, and quickly fell into the jazz scene, working with Cootie Williams, Art Blakey, Charles Mingus and others.

On piano, Redd was never the most dynamic improviser, but his keen ear and deep attunement to song form made him a striking “A busy chorder, he will start rattling away behind a soloist, prompting him and prodding hard,” Watrous wrote. “Chords jar and fragment. New rhythmic and harmonic ideas pop up regularly.”

The Connection provided a unique career opportunity for Redd, as well as a groundbreaking dramatic innovation. At one point in the play, a character says the police are on the way. In the script, they never do, but one night they did.

“A knock came on the door,” Red in 2012, “and when the gentleman who was the head actor [playing the character] Leach, he opened the door, there was a real uniformed policeman there. Jackie McLean had gotten the policeman on the beat to come up and stand there. So we all thought we were being busted.”

Redd recorded a third album, Redd’s Blues, for Blue Note in 1961, but producer Francis Wolff decided not to release it at the time. It finally saw daylight in 1988. By then, Redd’s career had taken a downward turn: he’d moved to Europe in the ’70s, then to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he became a local stalwart. He released dozens of albums, on labels including Milestone and Steeplechase.

A decade ago, Redd moved to Baltimore, establishing a presence there and in Washington, D.C. He formed relationships with locals like saxophonist Brad Linde, who features Redd on a pair of new albums, Baltimore Jazz Loft and Reminiscing.

“Playing with Freddie gave me the same feeling as listening to his music,” Linde tells WBGO. “It was joyful, toe-tapping, and supremely lyrical. His melodies (composed or improvised) were thoughtful, his harmonies wholly original and inevitable, and his touch was crisp and clear.”

He adds: “The highlight for me was his comping. He was constantly composing his accompaniment. His left hand was full of counterpoint, pedal points, and voice-leading surprises. His right hand would alternate block chords with independent conversations with the soloist and blues inflections. After each solo, he’d wait to catch my eye, grinning and nodding in approval before taking his own solo. He was a consummate composer and an authentic gem from the heyday of bebop.”

Jimmie Morales, one of Puerto Rico’s most prolific percussionists, died on March 16 at his home in Gurabo, Puerto Rico. He was 63.

His family shared news of his passing on social media, without stating a cause.

Highly respected as a live performer as well as a studio musician, Morales had a long and celebrated association with Gilberto Santa Rosa. He appeared on more than 250 recordings, primarily as a conguero. His signature sound was a defined slap — known by players as golpe seco (dry stroke) — that is used to keep time within the repetitive patterns known as tumbaos. Because of this trademark, he became known by a nickname, “Mr. Slap.”

A Conguero’s Conguero: A Memoir of Jimmie Morales, a new book by Bella Martínez with a translation by Ronald P.S. Vázquez, confirms the high regard with which Morales was held by his peers. Among them is the famed bongocero Johnny “Dandy” Rodríguez. “Jimmie is one of the best congueros I’ve ever met,” he says. “His complimentary style adapts to the needs of any orchestra in which he plays. He is a tremendous accompanying musician.”

Morales first came to public attention with the orchestra of famed bandleader and timbale player Willie Rosario, where he spent eight years performing all over Latin America and stateside. Rosario had a reputation for a rhythm section that ran like a well-oiled machine, earning the nom de plum “Mr. Afinque” (Mr. Tight Rhythm). With Morales in the conga chair, the orchestra achieved great success on albums now considered classics, like From the Depth of My Brain, El Rey Del Ritmo, and Nuevos Horizontes.

Percussionist and arranger José Madera, who met Morales in the context of the Rosario band, describes his contribution as unique. “I had written three or four hit arrangements for them and so that’s when I first saw him play,” Madera says. “In my humble opinion he was the best conga player that Willie Rosario’s orchestra ever had.”

David Rosado Cuba, who played timbales in groups with Jimmie on many an occasion, extends that praise to virtually any musical setting. “Playing alongside Jimmie was like riding first class on an airplane,” he says. “He was an inspiration to everyone who ever performed or recorded with him.”

By his high school years, Morales was an avid record collector, and with his photographic memory he became an expert on the entire catalogue produced by Fania Records. The industry leader in the genre, Fania had a roster of the best-known artists of the day. One of them would become Jimmy’s hero: conguero and future National Endowment of The Arts Jazz Master Ray Barretto.

Morales worked locally — with vocalist Tito Allen, Beto Tirado’s la Predilecta and others —while studying to become an orthopedic technician. Then bassist Edwin Morales (no relation), the leader of Mulenze, asked him to record a conga track for the tune “No Hay Manera Filomena.” Three others had failed before him, and his performance opened the door to eventually become the most sought-after conguero on the island.

His association with Willie Rosario began in 1978, when conguero Papo Pepin left the band to work with Roberto Roena and His Apollo Sound. In many ways, the Rosario band was modeled after that of legendary Puerto Rican vocalist Tito Rodríguez and his orchestra. A member of the Big 3 (along with Machito and Tito Puente) Rodríguez was a stickler for rhythmic precision to match his pristine voice. It has been said that he wouldn’t allow his timbale player to venture a fill without his permission.

It is this aesthetic, serving the needs of the vocalist and the dancer, that Morales came to experience under Rosario’s tutelage. “From Willie,” says David Rosado Cuba, “Jimmie learned the value of teamwork, discipline, professionalism, punctuality. Willie really mentored him even showing Jimmie about how to tune the congas for performing in a band.”

Morales also brought a rhythmic intensity that was the perfect match for Rosario’s disciplined sense of tempo. To this the orchestra would eventually add two singers who would become salsa icons: Tony Vega and Gilberto Santa Rosa.

“When you hear those recordings that Jimmie did with Willie, and the later ones with Gilberto Santa Rosa or anyone else he recorded with, what can I say?” reflects conguero Eddie Montalvo, of the Fania All-Stars. “The secret is Jimmie. The hip little repiques (fills) he does between phrases are just ridiculous. And that slap he has has been copied by everyone.”

As Jimmie’s reputation increased, he was asked to contribute to other artists’ productions. His technical studies with David “La Mole” Ortiz, and his growth as a sight-reading musician, further enhanced his unique gift to serve the music. Mr. Slap would soon find himself working with almost every salsa vocalist of note: Pellín Rodríguez, Andy Montañez, Frankie Ruiz, Eddie Santiago, Ismael Miranda, Oscar D’León, Marc Anthony and more.

In 1986, Morales left the Willie Rosario Orchestra to join “The Gentleman of Salsa,” Gilberto Santa Rosa, with his own band. Santa Rosa would rise to become the most important vocalist in salsa, selling out performances at Carnegie Hall and establishing a global gold standard for production in the studio and live performance. Morales was a core collaborator: their musical relationship lasted up until his death.

Morales was associated with the Latin Percussion and Remo brands, designing his own line of Remo congas. He did the same for TOCA Percussion, traveling worldwide as a clinician.

When Jimmy Morales’ name is mentioned in musician circles, his work ethic, professionalism and musicality are always implicit. But the quality treasured most by those close to him is his humility and gratitude. “Jimmie was the humblest of musicians,” attests the young percussionist David Antonio Rosado. “He always wanted to help you and the music in any way he could.”

More Stories

Eric Gales՛s new album 2025, releases single with Buddy Guy & Roosevelt Collier: Video, CD cover

I usually practice with the door open. I always played like that, hoping someone would walk by and discover me: Ahmad Jamal once confessed: Video, Photos

Terry Riley. A landmark reissue of one of the most important figures in 20th-century music: Videos, Photos