A beast on the bass, a pioneer of jazz-fusion and a fashion icon – Stephen “Thundercat” Bruner is all these things. Get to know how this complex human fell hard but landed on his feet.

“Being able to laugh is one of the best feelings ever. It’s an important part of life, maybe more so than music.” This is a surprising statement when you consider its source – Stephen Lee Bruner, the bass maestro, funk virtuoso and genre-bending producer better known for his alter ego, Thundercat. It’s November 2021 in St Louis, Missouri, and Bruner is enjoying a rare day off from his five-month North American tour to wax philosophical with The Red Bulletin. But, as they say, time flies when you’re having fun – and this guy knows how to have fun.

The 37-year-old Los Angeleno is a musical genius with a sound that flits between jazz-funk fusion, electronica, soul, hip-hop, R ‘n’ B, psychedelia and genres even further afield, and is impossible to categorise, even by his most devoted fans, of whom there are many worldwide.

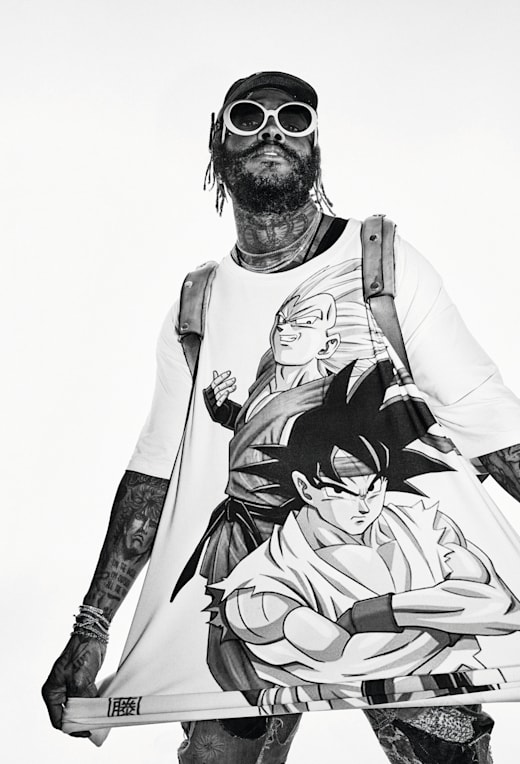

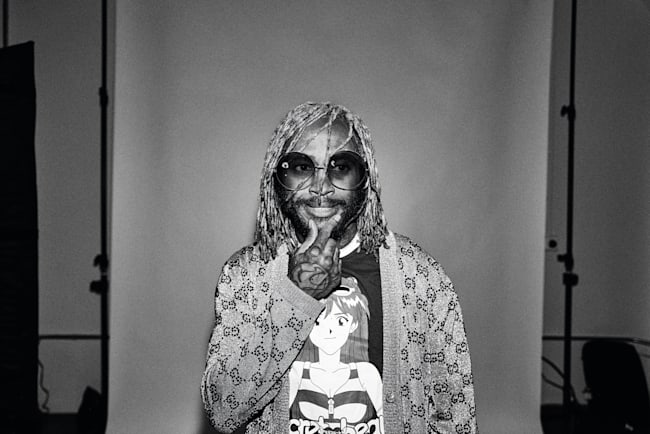

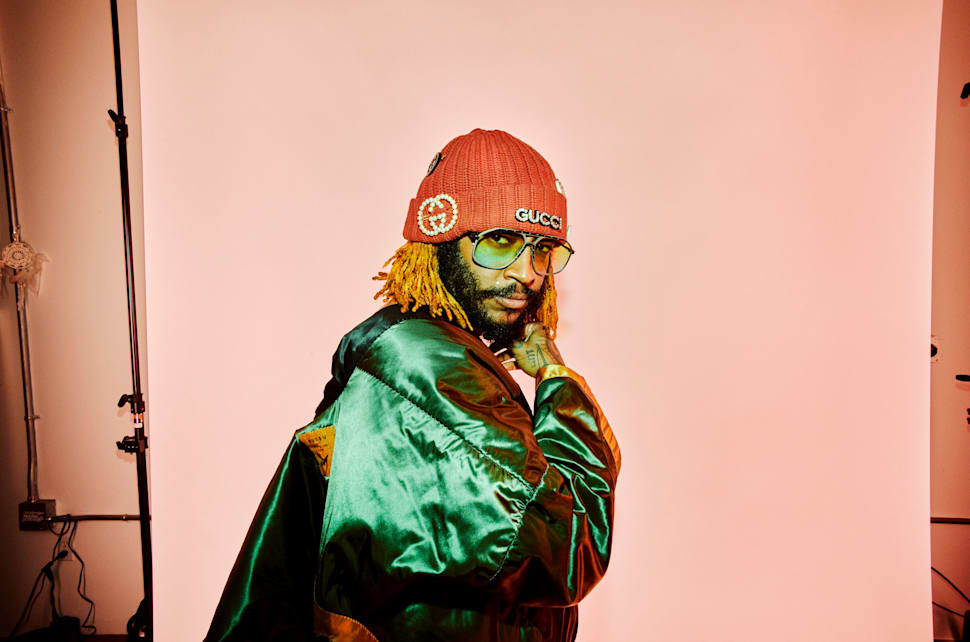

This music artist has a style all of his own

I have to be careful I don’t blow all my cash on anime

Just as chaotic and creative is his personality; Thundercat is known for his eccentric fashion taste – he’ll team haute couture with a Pikachu backpack – along with pop-culture geekiness, scatter-brained humour and farcical japes. He once played an hour-long jam session with Canadian indie rocker Mac Demarco where both were stark naked. And he announced the tour for his 2020 album, It Is What It Is – arguably his most complex, emotionally raw and personal release to date – with an online video in which he simulated making passionate love to a Pokémon Snorlax toy.

Our interview takes place a decade after the release of Thundercat’s debut album, 2011’s The Golden Age of Apocalypse. “It’s crazy to think it’s been a solid 10 years,” he says of the anniversary. “It’s trippy because of all the places I’ve been to, psychologically, over the last decade. I remember when it was just me and Austin Peralta rolling around with his keyboards and my bass.”

Many things have changed in Bruner’s life since those days spent lugging instruments around with Peralta, his jazz pianist/composer friend who died in 2012 from viral pneumonia, and about whom much of Thundercat’s 2013 album Apocalypse was written. But his loveable, eccentric persona remains present and correct – outwardly at least.

He’s still more interested in sitting on his couch, binge-watching cartoons than attending Hollywood’s hottest showbiz parties. “I’m a huge anime nerd,” Bruner says of his obsession with Japanese animation. “That hasn’t changed, and it never will. It’s just now I have money to spend on the things I’m passionate about. Although I have to be careful I don’t blow all my cash on anime.” This low-key approach to celebrity life checks out – when asked about his rider for our cover shoot, Bruner didn’t demand expensive champagne or M&Ms separated by colour; he asked for a bowl of blueberries. If only all rock stars were so unpretentious.

It’s easy to forget that beneath the vibrant outfits and the fluffy cat’s-ear headbands, Bruner is one of the most sought-after instrumentalists, collaborators and producers around. A two-time Grammy-winning artist who has released four albums as Thundercat, he also boasts a client list that reads like a who’s-who of popular music – Snoop Dogg, Childish Gambino, Ariana Grande and Erykah Badu are just a handful who have made the call.

In 2015, he collaborated with Kendrick Lamar on the rapper’s To Pimp a Butterfly album, helping to deliver what is widely considered to be Lamar’s masterpiece (it’s ranked 19th in Rolling Stone’s ‘500 Greatest Albums of All Time’ list) and winning his first Grammy, for his work on the track These Walls. “How [Lamar] spanned the walls in the verses, and where he took it – he went from prison to pussy – I was overwhelmed when I first heard that track,” says Bruner of the song’s complexity. “I didn’t know how to process it, let alone the idea that it was up for a Grammy.”

Bruner was born to be a musician. His father, Ronald Sr, is a veteran drummer who played with the likes of The Temptations, Diana Ross and the Supremes and Gladys Knight, and; his mother, Pamela, is a flautist and percussionist. Older brother Ronald Jr is also a drummer and won the Grammy for Best Contemporary Jazz Album in 2011 with The Stanley Clarke Band. And his younger brother, Jameel, played keyboards for LA music collective The Internet and is now a solo artist under the name Kintaro.

Growing up in the ’90s, Bruner would fight with his brothers for the TV remote. They’d want to watch VHS tapes; he wanted ownership of the screen to play video games. But in the background there was always jazz playing, performed by the likes of Jimmy Cobb, Vinnie Colaiuta, Tony Williams and Billy Cobham, and Bruner was paying close attention.

“My brothers thought I wasn’t listening,” he says. “They thought I was just being an obnoxious kid. But music is all-encompassing. I got the message quite early about what it can do. There’s always been something about music that has touched base with me mentally, psychologically and emotionally. Probably even spiritually.”

Thundercat’s It Is What It Is album won a Grammy Award in 2021

I’m still learning about myself, and I’m going to continue to get better

Bruner first picked up a bass guitar at around the age of four, and as he became more proficient he’d practise by playing along to the soundtrack of the 1991 action-comedy film Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: Secret of the Ooze. It was his love of cartoons and anime that spawned his stage name – a reference to ThunderCats, the popular ’80s US cartoon about cat-like humanoid warriors. By the early 2000s, he was touring the world as part of “multicultural pop group” No Curfew, and in 2002 he joined thrash band Suicidal Tendencies (his brother Ronald Jr was their drummer at the time).

After that, Bruner became a bass player for hire, rising through the ranks of the LA music scene alongside childhood friend and jazz paragon Kamasi Washington, who drove them from gig to gig in his beaten-up 1982 Ford Mustang with parts of its interior held together by duct tape. “It’s like we’ve just been big kids this whole time,” he says of Washington. “Like we’re still 15. It’s always been fun for us. We see each other, we laugh, we’ve always got some funny shit to tell each other about life.”

It was a chance meeting with LA rapper and producer Steven Ellison, aka Flying Lotus, at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas, in the late 2000s that pushed Bruner’s music to the next level. Ellison signed Thundercat to his independent record label, Brainfeeder, and has released every one of his albums for the past decade, but he’s proved to be far more than just a label boss. The two producers have become a formidable musical pairing, collaborating on a variety of projects over the years, including their own individual albums and the score for Donald ‘Childish Gambino’ Glover’s hit US TV show Atlanta. “We’re like Batman and Robin,” says Bruner. “I’ve been swinging around doing a bunch of weird shit while he’s just in the shadows.”

Popping his head out from the shadows for one particularly crucial moment, Ellison encouraged Bruner to start singing. “He saw something that I didn’t,” says Bruner. “I had a conversation with [US rapper] J Cole recently. He was picking my brain, and there was this moment where I realised just how much I trust Lotus. When I think back to that moment, that’s what I felt: I trusted my friend, and he was right.”

Thundercat wears many hats in his music and his style

© Wolfgang Zac

Awards, money, creative projects pouring in from every direction, a long list of music

icons he can now call friends – to an outsider, Bruner’s life would appear to have improved with each passing year. But nothing is ever quite as it seems, and the reality of the last few years has been hard for him. As well as releasing an album during a pandemic and ending a long-term relationship, Bruner mourned the loss of one of his closest friends, Mac Miller, the Pittsburgh rapper and producer who died from an accidental drug overdose in September 2018.

The pair were not only fierce friends, but frequent collaborators. Their most memorable team-up was a performance for US National Public Radio’s Tiny Desk Concerts series, recorded just a month before Miller’s death. The story surrounding the session is now legendary: Bruner was on a European tour when he received a message from Miller asking him to fly over and perform. This would mean Bruner not only cancelling multiple tour dates but flying from Eastern Europe to Washington DC for what was essentially just a 17-minute gig. He did it. “[Mac] wanted to feel comfortable in front of everybody,” Bruner has since said. “He wanted me to be there beside him.”

When you watch the intimate performance, their love for each other is clear – acutely in sync and in their element, they joke back and forth like blood brothers. Thundercat, sporting red-and-gold Muay Thai boxing shorts and pink braids, switches between rattling a shaker and playing his custom Ibanez six-string bass. Miller adopts an almost Frank Sinatra-like persona; a suave operator with a nervous disposition, he playfully fumbles through segues with a clownish temperament before snapping back into performer mode to deliver the vocal parts. “That was a special moment,” Bruner remembers. “I never missed a chance to tell Mac I loved him. And that’s because I really did.”

Thundercat’s 2020 album It Is What It Is provided an opportunity for Bruner to channel his grief over Miller’s death through his art. A space-age fusion of jazz, funk, hip-hop and pop, produced in collaboration with Flying Lotus, the release is an “open-ended love letter” to

his friend. “Albums are always an intense, painful experience,” says Bruner, “but that particular one changed my life.”

The title represents an acceptance that death is an unavoidable reality for us all. It’s also a nod to Miller himself, who used the phrase in the lyrics of What’s The Use?, a track on the last album the rapper released in his lifetime, 2018’s Swimming, which features Bruner on bass. On the title track of It Is What It Is, Bruner sings, “Hey, Mac,” right before Miller’s voice responds with a lonely “Woah”. “It was all I had,” says Bruner, recalling the recording process. “I had something to say in that moment, but to hear [the track] was so polarising for me. I couldn’t listen to it without emotionally breaking down every time. But that’s

just what it was, up until the last minute of saying goodbye to Mac.”

The album’s creation took a huge toll on Bruner, both mentally and physically. He had fallen into depression. He wasn’t eating or sleeping right, and he was using alcohol to numb the pain. The fun-loving, Gucci-sporting boy wonder who could light up any room was almost unrecognisable. It wasn’t easy to turn to music – the thing that connected him and Mac – for solace. “It almost felt like a ghost in the machine, or muscle memory,” Bruner recalls. “Making music through that period, I don’t know how I did it. On one hand, it’s what I do; on the other, it was a lot to process.”

Stephen Lee Bruner, aka Thundercat

Bruner was forced to face some hard truths about his lifestyle. “Drinking had given me comfort for years,” he explains. “I would often just wash over it, and the degree to which I did scared people. I’ve watched multiple friends who’ve died in front of me, all in such a volatile way – from Austin to Zane Musa [the famed US jazz-funk saxophonist who died from a fall in 2015, aged 36] to Tim Williams [Bruner’s replacement as bass guitarist of Suicidal Tendencies, who died in 2014] to Mac. I had to take it seriously. I could see what was going to happen. It felt like if I washed over it again, I was going to die. I had to hit the reset button.”

After this crucial realisation, Bruner introduced some vital self-care measures into his daily routine. First, he stopped drinking. “I only had two options: turn to the bottle or not,”

he explains. “It felt like that decision was already carved in stone for me at that point.” He also went vegan and started therapy. Then, when the pandemic forced the world to shut down, Bruner took up boxing and kickboxing. “I’ve never been a person to participate in physical activities. This is maybe the first time that I’ve ever been this serious about something other than illustration and playing bass.”

Something else that helped was listening to Drake’s most recent album, Certified Lover Boy. On the day of its release in September last year, Bruner tweeted, “Sometime it take a Drake album to get you back in focus.” The Toronto-born star has often faced criticism from hip-hop fans who view his emotional, introspective brand of rap as ‘soft’, but Bruner recognises a kinship in that vulnerability. “Drake will always remind you that you’re not alone,” he explains. “Some cats put out an album and you know what to expect – it’s going to shoot the club up. Drake will pour his heart and soul into his music,

and you can hear it. It’s why people make fun of him. But he’s baring his soul in his music.”

Certified Lover Boy proved to be just the motivation Bruner needed to reignite his own sense of purpose. “It knocked me out of the weird flight pattern that I was in with trauma,” he says. “Every time I’d look at stuff, I’d see it with this damaged set of eyes. It’s hard to find a way out of that emotionally. Hearing Drake’s album, it felt like, ‘I feel you, bro.’ It was a reminder that I’m not alone.”

Now three years sober, Bruner is in a much better space. As he readies himself for the start of his European tour, which kicks off in Glasgow at the end of March, the enigmatic goofball persona has returned. But beneath it all, Bruner is a changed man. Does he think he’ll ever drink again? “I don’t know,” he replies. “It’s been a long three years. I don’t feel the same about it anymore. There’s a part of me where it’s still related to the trauma, but at the same time I’m just kind of like, ‘I’ll deal with that when I get there.’”

As for Collins, the innovative bassist who rose to prominence in the ’70s, playing alongside the likes of James Brown and George Clinton, Bruner says working with him was “a full circle moment”. He recalls one of the Silk Sonic sessions where he got to hold Collins’ iconic rhinestone-encrusted, star-patterned ‘Bootzilla’ glasses, as featured on the cover of the 1978 Bootsy’s Rubber Band album Bootsy? Player Of the Year. “They’re iconic not just because they’re Bootsy’s,” says Bruner, “but because of where they come from and what they represent in the art. To be able to hold the original pair was really good for my soul. They inspired me to be more myself and not be shy about it at all.”

They say a cat has nine lives. At the age of 37, Bruner has certainly experienced enough to fill that quota, and along the way, he’s lost more soulmates than many people would be fortunate enough to find. He’s also achieved more in his career than many artists could ever dream of. But Thundercat isn’t ready to rest on his laurels just yet, nor to surrender to the arrogance that can plague those who have become wildly successful, especially given everything he’s endured in recent years.

“I’m still learning about myself,” he says, “and I’m going to continue to get better.”

Thundercat has given himself a second chance, and he’s not about to squander it.

More Stories

Eric Gales՛s new album 2025, releases single with Buddy Guy & Roosevelt Collier: Video, CD cover

I usually practice with the door open. I always played like that, hoping someone would walk by and discover me: Ahmad Jamal once confessed: Video, Photos

Terry Riley. A landmark reissue of one of the most important figures in 20th-century music: Videos, Photos