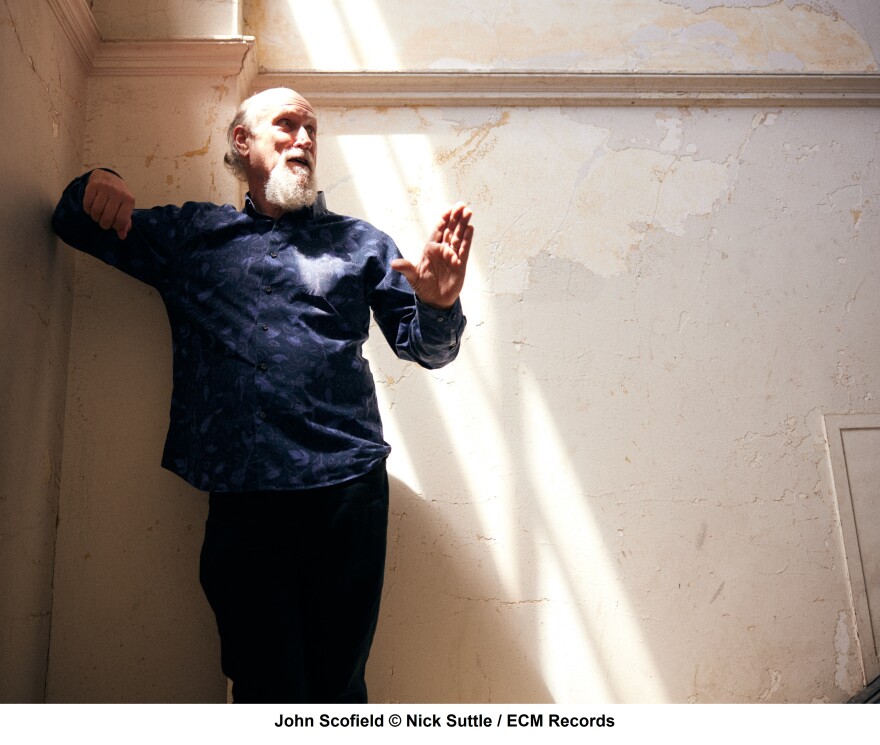

The gemlike new album by John Scofield — simply titled John Scofield, releasing Friday on ECM — finds him alone with his guitar, balancing choice covers with original tunes. It’s the first solo guitar album of Scofield’s nearly 50-year recording career. There are a few reasons for that, which he enumerated when we connected by phone this week.

Scofield, who lives in Katonah, NY, made his new album last August, during an uncharacteristically long period at home. He has since gone back on the road: his new band, the groove-forward Yankee Go Home, played the Blue Note in February, followed by a string of dates across the country. (I caught the band — with keyboardist Jon Cowherd, bassist Vicente Archer and drummer Josh Dion — at the Ardmore Music Hall.)

One of the highlights of John Scofield is a medium-uptempo jaunt through the songbook standard “It Could Happen to You,” which we are proud to premiere here. A lightly edited transcript of our conversation is below.

Yeah, and you know, that’s the fun thing you got to do is make up some name for your basement, you know? In my case, the attic. Yeah, I did.

And is that the first time that you’ve released an album that you recorded?

Yeah. Absolutely. I didn’t ever have the wherewithal or the stuff to do it. And there have been some technological changes. Universal Audio makes this thing so I can get the sound going through my Fender amp, and then does a speaker modeling. So it goes direct but it’s a speaker, you know? Because of that, I can go right into GarageBand, because it’s just two tracks of guitar. The looper is on one track, and then my in-time guitar is on the other. So yeah, I was able to do it at home with absolutely no engineering or technical know-how.

You know, I’ve talked to so many musicians about this: obviously the pandemic has been devastating in so many ways, but then every once awhile it reveals new possibilities.

Yeah. Well, I would not have made a solo record, I bet, if it hadn’t been for the being home all the time. Because what I really like to do most of all, you know, is to try and play rhythmically with other elements. Not just by myself. I’ve never really thought about a solo record, but then I started playing with a looper, and I had that for years and years. And I thought, “Well, what the hell, just do it with this in order to play some hot jazz, you know?” Then the other thing was, I didn’t really look forward to going into a recording studio by myself. Just the idea of saying, “Well, we’ve got eight hours to do it,” and I just thought I might start panicking or something. I’ve never done that by myself, and it just seemed weird. So I had never thought of making a solo record.

Wait a minute. I think I did. I guess this is dementia here, because I completely forgot about that. But that was different because I think I did it on my nylon-string guitar.

That’s the reason I remember it so clearly — because you have such a such a recognizable sound. And then when I heard you play this nylon-string solo gig, I was blown away because it was still your sound. I realized how much it’s about the touch and the intention, you know?

Yeah. Well, it is, it really is. I mean, and you know, when I play nylon, I play with a pick. So it’s, really not so different from what I play on the electric, you know, but it’s a nylon-string so sonically it’s different. Wow, thanks for remembering that, because there’s only the seed of a memory of that. Maybe I blocked it out. But also, that would be cool, to do more nylon-string solo playing; I sort of just don’t even think about it.

Well, when I realized this was your first solo album, it raised the question of what took so long. You sort of answered that when you mentioned how you’re always seeking interaction. So on this album, you’ve set up an artificial interaction with another musician, which is yourself.

Right.

So it’s like a solo-duo album, in a certain way.

Yeah, it is. It’s not, you know, straight solo guitar — but the other guy is me. I noticed that, you know how if you’re just playing something and the band’s going “chug, chug-a chug chug,” and you play your phrase and then you listen to them, and you sort of do this little thing where you leave space. Your brain just jumps in on top of it. And I always thought of that as really playing off something, or playing with those guys. I was doing the same thing with myself, and it was as if myself was listening to me. It’s funny.

Let’s talk about your version of “It Could Happen to You.” Can you talk about your approach to that standard?

Well, it’s a song that I’ve known for a long time. And I think I said in the liner notes that I really love this Kenny Dorham record that I had, where he played it. I had that album a long time ago, and it’s probably the first time I learned it. And it’s a standard that’s been done five zillion times, but I love the great songs, you know? And that’s one of them.

Yeah, exactly. Yeah — and of course, Miles Davis, so another trumpet player played it. Everybody knows the Miles version. And, uh: “Hide your heart from sight, lock your dreams at night / It could happen to you. Don’t go counting stars ‘cause you may stumble / Someone drops a sight and down you tumble.” It’s a song about: Hey buddy, watch out, you’ll be in love — ho ho ho. “All I did was wonder how your arms would be / And it happened to me.” Yeah. It’s a saloon song right from Jimmy Van Heusen.

With lyrics by Johnny Burke.

Yeah, Johnny Burke. Do you know Steve Khan? His dad was also one of the lyricists with Van Heusen: Sammy Cahn. Anyway: yeah, you know, it’s a wonderful song, and I would hesitate to say “They don’t write ‘em like they used to,” you know. Because they don’t write ‘em like they used to — but there’s a reason for that, because everything changes. And, you know, they write stuff that’s really incredible that’s just different. That’s from this great era, and then it was taken by Miles and those guys and made into modern jazz, and it’s still compelling to try and improvise on. It’s got great changes, basically. Just trying to swing, that’s the whole thing.

Well, the solo you play, especially as you get deeper into the tune — there are some fun surprises in your phrasing and articulation. It struck me that some of that is all the more foregrounded on this really sparse setting, and might get a little more lost if you were playing with a rhythm section.

Yeah, absolutely. And that’s the nice thing about solo. Yeah, I like to hear, you know, guitar players play solo, just to really hear them play the instrument, too.

One little bit of clarification about the looper. Is this all constructed in real time?

Yeah. Because my looper can’t remember anything but what you just put in there. I have the Boomerang, and it’s the old version. On this performance, I recorded the loop and then turned “record” on. Some of the other tunes, you can hear me playing what becomes the loop. But on this one, I cheated. The way I get around that on the gig: you might have noticed before, I knew the lyrics, right? That’s because when I’m making the loop in real time on solo gigs, I’ll recite the lyrics at the same time. And then it covers up me just playing the changes. Which, sometimes the changes are cool. The song on the album called “Mrs. Scofield’s Waltz,” I do just play the changes on that one first, and then go into playing. So you can hear me making the loop on that one. But the fact that you can’t store loops, I like that. Because otherwise the temptation would be to have a whole recorded thing, and you’d be playing with tracks. Which is not the same.

More Stories

Eric Gales՛s new album 2025, releases single with Buddy Guy & Roosevelt Collier: Video, CD cover

I usually practice with the door open. I always played like that, hoping someone would walk by and discover me: Ahmad Jamal once confessed: Video, Photos

Terry Riley. A landmark reissue of one of the most important figures in 20th-century music: Videos, Photos