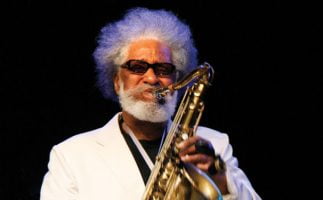

07.09. – Happy Birthday!!! One of the last in a generation of jazz greats, Sonny Rollins once thought music could change the world. His optimism about humanity has since vanished but, at 85, he still has much he wants to say.

The “Saxophone Colossus”, a nickname that was also the title of his seminal 1956 album, is among a handful of sax players including John Coltrane, Charlie Parker and Coleman Hawkins who defined the instrument, with Rollins creating a heavy-charging, mordant style that was also readily experimental.

The hard-working tenor saxophonist has taken several extended sabbaticals, most famously when he temporarily retired – yet would practice on New York’s Williamsburg Bridge. He later moved to India and Japan to explore spirituality.

His latest break is less intentional – respiratory problems have kept him from playing since 2012.

“I am not finished with what I want to do musically, so I definitely want to do more and I am hoping that I will be able to,” Rollins said in a reflective interview on a career spanning more than 65 years.

Rollins voiced confidence that “new, modern medication” would help him return to form. Eager to keep releasing music in the meantime, he has been reaching into his vault of live recordings to put out collections.

His latest, Holding the Stage: Road Shows, Vol. 4, features 10 tracks, some of them never recorded in studio, of performances since 1979 across the United States and Europe.

Highlights include songs from his nerve-wracking yet emotionally resonant performance that he went ahead with days after the September 11, 2001 attacks, which the native New Yorker witnessed firsthand as he lived near the fallen World Trade Center.

Fueling his desire to record, Rollins said he saw music as commentary on happenings around him. Another of his classic works, 1958’s Freedom Suite, was driven by a strong, confident tenor sax that reflected the burgeoning movement for African American civil rights.

The saxophone legend now says he is no longer driven by current events and instead wants to reflect musically on “the bigger picture – not this world, the infinite world”.

In the Sixties, Rollins said that he and like-minded artists “were thinking that music could change the world”.

“At one time in my life I thought that this world could change and get more peaceful, with everybody loving each other and all this hope. But then I learned, and I lived a little longer,” he said.

“I realised that this world will never change. This world is meant to be a place of war, killing, everything – sickness, illness, death. That’s this world.”

Rollins – mellow and affable with his striking shock of white hair – however does not sound bitter, rather believing that the “purpose of life is to serve others” – in his case, by bringing joy through music.

“I’m very fortunate that I was blessed to live my life playing my music,” he said.

Raised in Harlem to parents from the US Virgin Islands, Rollins was inspired into a career in music when Frank Sinatra visited his school and successfully appealed to end fighting between young Italian and African Americans.

By his twenties, Rollins had managed to play with some of the biggest names in jazz history including Parker, Miles Davis, Max Roach and Thelonious Monk, with the young Rollins hanging out at the pianist’s apartment and playing on Monk’s classic 1957 album Brilliant Corners.

His most complicated relationship may have been with Coltrane, who was a friend but often described as a rival until Coltrane’s death from cancer in 1967.

Rollins called Coltrane “a beautiful, beautiful human being” and said that he had struggled as a young prodigy to fit in with the legends.

“I look back on my relationship with Coltrane, and my relationship with Monk – a lot of stupid things I did with those people that I would not have done if I was more mature,” he said.

Rollins nevertheless said he had no regrets musically about his past. Besides his playing style of heavy inflections, Rollins pioneered jazz performances without piano and was perhaps most inventive with his improvisation in rhythm.

St Thomas, his best-known song, incorporated Caribbean calypso he remembered as a child. Most known for his hard bop, Rollins later played with The Rolling Stones and brought elements of rock and even disco into his own music.

Two jazz legends close to Rollins, Ornette Coleman and Horace Silver, have died since 2014. Coleman was instrumental in the creation of flowing “free jazz”, while Silver, a frequent collaborator who is eulogised musically on Rollins’ latest album, was a leading hard bop pianist.

“We are not supposed to be in this world forever, so you can’t look at so-called death as some kind of bad thing,” Rollins said of his friends.

“They gave the world jazz, which is a never-ending phenomenon. That is wonderful.”

Rollins credited his longevity in part to yoga, which has helped him concentrate and to stay off drugs and drinking after trouble in his youth.

But mostly, he points to his creative spirit.

“I’m still alive because I’m still learning.”

More Stories

Don’t forget Vic Juris – He always very attentive to the internal dynamics of a world-class “guitar-oriented”: Video, Photos

Swamp Dogg as one of the most eccentric and influential cult figures in Blues, Soul & American music։ Video, Photo

He traditionally began his concerts by introducing himself in a simple manner by saying, Hello, I’m Johnny Cash: Video, Photos