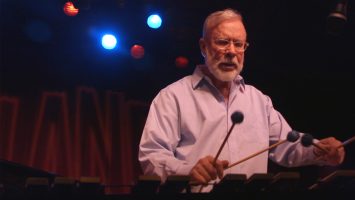

In his introduction to Learning to Listen, master vibraphonist Gary Burton offers readers the choice of absorbing his story as either that of “a gay jazz musician or … a jazz-playing gay man, whichever you prefer.”

This declaration might potentially put off jazz fans with no particular interest in LGBT issues. But Burton’s book is a jazz story first and foremost, and his compelling chronicle of his sexual-identity struggles in no way diminishes the musical material that, for most readers, will be the book’s raison d’être.

Born into a typical Indiana household, Burton became a professional musician at an early age; the book’s photo section reproduces a business card from 1952, when Burton was 9 years old. Eschewing formal music education for the life of a touring musician, he made his mark in the bands of George Shearing and the maddeningly mercurial Stan Getz before striking out on his own in the late ’60s. His bands of the era, featuring electric guitars and basses, were the earliest examples of the fusion style later adopted by Miles Davis and other previously acoustic artists. Burton provides richly detailed accounts of the frequently frantic touring life; his seminal collaborations with Chick Corea, Pat Metheny and tango giant Astor Piazzolla; and his longtime tenure as an instructor and administrator at the Berklee College of Music, where he was responsible for integrating new musical technology and rock idioms into the school’s curriculum.

Along with this jazz-historical material, Burton adds to the ever-expanding LGBT library with the story of his battle to come to terms with his sexuality within the overwhelmingly macho world of jazz. Beginning in his youth, Burton contended with feelings for men that he couldn’t reconcile with his occasional attractions to women, and he forthrightly acknowledges his fear of accepting the truth about his sexual preference. He discusses his therapeutic contention with his gayness, the recognition of “homosexual tendencies” that exempted him from the draft in the early ’60s, and the two marriages that, while loving and genuine, negated the central issue of Burton’s quest for self-definition. Burton came out in the early ’90s, and he now lives as a securely out-and-proud gay man, with a longtime partner, good relations with his ex-wives and his children, and strong acceptance from his colleagues in the jazz community.

Burton’s prose is as crisp and fluid as his playing. He is unafraid to call out musicians with whom he has had unpleasant personal or professional interactions, and he shares a fascinatingly idiosyncratic philosophy on music and its performance. Burton confesses that he is not one for much extensive practice; he is well known among his peers for the “twenty-minute practice session,” and admits that unless he’s touring, recording or preparing new music, his vibes rarely leave his garage. Near the end of the book, Burton provides an in-depth discussion of his musical process, detailing the dialogue with his “inner player” and the musician’s responsibility to “show the listener around the song.” This chapter, titled “Understanding the Creative Process,” is as cogent and intriguing an analysis of the musician’s method as any I’ve read.

Learning to Listen proves a strikingly apt title for Burton’s memoir. This compulsively readable work gives us not only a man learning to listen to his inner artist, but also to hear, understand and express the truth of who he is and how he is meant to love and live to his fullest. This is not only an essential jazz biography but also a singular addition to the gay literary canon, one that deserves to find and cultivate a strong LGBT readership.

More Stories

A book inside jazz. Rodolfo Cervetto: The sounds of life. three stories about jazz: Video, Photos

Blues remains hidden within countless forms of music: New book explores buried Chicago Blues history: Photos, Video

When jazz came to Europe: The American Dream? That’s right – pull yourself up by your bootstraps. But what happens if you don’t have any boots? Video, Photos