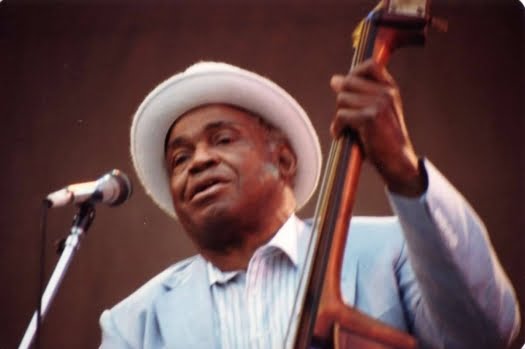

01.07. – Happy Birthday !!! Willie Dixon was born and raised in Mississippi, he rode the rails to Chicago during the Great Depression and became the primary blues songwriter and producer for Chess Records. Dixon’s songs literally created the so-called “Chicago blues sound” and were recorded by such blues artists as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Koko Taylor, and many others.

Willie Dixon was born on July 1, 1915, in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Vicksburg was a lively town located on the Mississippi River midway between New Orleans and Memphis. As a youth, Dixon heard a variety of blues, dixieland, and ragtime musicians performing on the streets, at picnics and other community functions, and in the clubs near his home where he would listen to them from the sidewalk.

Dixon grew up in an integrated neighborhood on the northern edge of Vicksburg, where his mother ran a small restaurant. The family of seven children lived behind the restaurant, and next to the restaurant was Curley’s Barrelhouse. Listening from the street, Dixon, then about eight years old, heard bluesmen Little Brother Montgomery and Charley Patton perform there along with a variety of ragtime and dixieland piano players.

Dixon was only twelve when he first landed in jail and was sent to a county farm for stealing some fixtures from an old torn-down house. He recalled, “That’s when I really learned about the blues. I had heard ’em with the music and took ’em to be an enjoyable thing but after I heard these guys down there moaning and groaning these really down-to-earth blues, I began to inquire about ’em…. I really began to find out what the blues meant to black people, how it gave them consolation to be able to think these things over and sing them to themselves or let other people know what they had in mind and how they resented various things in life.”

About a year later Dixon was caught by the local authorities near Clarksdale, Mississippi, and arrested for hoboing. He was given thirty days at the Harvey Allen County Farm, located near the infamous Parchman Farm prison. At the Allen Farm, Dixon saw many prisoners being mistreated and beatenDixon himself was mistreated at the county farm, receiving a blow to his head that he said made him deaf for about four years. He managed to escape, though, and walked to Memphis, where he hopped a freight into Chicago. He stayed there briefly at his sister’s house, then went to New York for a short time before returning to Vicksburg.

When Dixon arrived in Chicago in 1936, he started training to be a boxer. He was in excellent physical condition from the heavy work he had been doing down south, and he was a big man as well. In 1937 he won the Illinois Golden Gloves in the novice heavyweight category. Throughout the late 1930s, Dixon was singing in Chicago with various gospel groups, some of which performed on the radio. Dixon had received good training in vocal harmony from Theo Phelps back in Vicksburg, where he sang bass with the Union Jubilee Singers. Around the same time, Leonard “Baby Doo” Caston gave Dixon his first musical instrument–a makeshift bass made out of an oil can and one string. Dixon, Caston, and some other musicians formed a group called the Five Breezes. They played around Chicago and in 1939 made a record that marked Dixon’s first appearance on vinyl.

In 1946 Dixon and Caston formed the Big Three Trio, named after the wartime “Big Three” of U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt, British prime minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet political leader Joseph Stalin. The group was modeled after other popular black vocal groups of the time, such as the Mills Brothers and the Ink Spots. Dixon by this time was singing and playing a regular upright bass. While Chicago blues musicians like Muddy Waters and Little Walter were playing to all-black audiences in small clubs, the Big Three Trio played large show clubs with capacities of three to five thousand.

In 1951 after several years of successful touring and recording, the Big Three Trio disbanded. Many of Dixon’s compositions were never recorded by the trio, but these songs turned up later in the repertoire of the blues artists Dixon worked with in the 1950s.

Leonard and Phil Chess began recording the blues in the late 1940s, and by 1950 the Chess brothers were releasing blues records on the label bearing their name. Over the next decade, Chess became what many consider to be the most important blues label in the world, releasing material by such blues giants as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and rhythm and blues artists like Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry. Many of the blues songs recorded at Chess were written, arranged, and produced by Willie Dixon.

Dixon was first used on recording sessions by the Chess brothers in the late 1940s, as his schedule allowed. After the Big Three Trio disbanded, Dixon became a full-time employee of Chess. He performed a variety of duties, including producing, arranging, leading the studio band, and playing bass.

Dixon’s first big break as a songwriter came when Muddy Waters recorded his “Hoochie Coochie Man” in 1954. Waters was one of Chess’s most popular artists and the song became Waters’s biggest hit, reaching Number Three on the rhythm and blues charts, Dixon became the label’s top songwriter. Chess also released Waters’s recordings of Dixon’s “I Just Wanna Make Love to You” and “I’m Ready” in 1954, and they both became Top Ten R & B hits.

In 1955 Dixon charted his first Number One hit when Little Walter recorded “My Babe,” a song that became a blues classic.One of Dixon’s most widely recorded songs, “My Babe” has been performed and recorded by artists as varied as the Everly Brothers, Elvis Presley, Ricky Nelson, the Righteous Brothers, Nancy Wilson, Ike and Tina Turner, and blues artists John Lee Hooker, Bo Diddley, and Lightnin’ Hopkins.

Dixon supplied Chess blues recording artists with songs for three years, from 1954 through 1956. At the end of 1956, however, he left the label over disputes regarding royalties and contracts. He continued to play on recording sessions at Chess, though, most notably providing bass on all of Chuck Berry’s sessions starting with the recording of “Maybelline” in 1955.

In 1957 Dixon joined the small independent Cobra Records, where he recorded such bluesmen as Otis Rush, Buddy Guy, and Magic Sam, creating what became known as the “West Side Sound.” It was a blues style that fused the Delta influence of classic Chicago blues with single-string lead guitar lines la B. B. King. The West Side gave birth to a less traditional, more modern blues sound and the emphasis placed on the guitar as a lead instrument ultimately proved to be a vastly influential force on the British blues crew in their formative stages.”

Gradually learning more about the music business, Dixon formed his own publishing company, Ghana Music, in 1957 and registered it with Broadcast Music Incorporated (BMI) to protect his copyright interest in his own songs. His “I Can’t Quit You Baby” was a Top Ten rhythm and blues hit for Otis Rush, but Cobra Records soon faced financial difficulties. By 1959 Dixon was back at Chess as a full-time employee. The late 1950s were a difficult time for bluesmen in Chicago, even as blues music was gaining popularity in other parts of the United States. In 1959 Dixon teamed up with an old friend, pianist Memphis Slim, to perform at the Newport Folk Festival in Newport, Rhode Island. They continued to play together at coffee houses and folk clubs throughout the country and eventually became key players in a folk and blues revival among young white audiences that achieved its height in the 1960s.

Dixon began internationalizing the blues when he went to England with Memphis Slim in 1960. Dixon performed as part of the First American Folk Blues Festival that toured Europe in 1962. Organized by German blues fans Horst Lippmann and Fritz Rau, the festival also included Memphis Slim, T-Bone Walker, John Lee Hooker, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and other blues musicians.

The American Folk Blues Festival ran from 1962 through 1971 and helped the blues reach an audience of young Europeans. American blues musicians soon found they could make more money playing in Europe than in Chicago. They played in concert halls and were reportedly treated like royalty. Dixon played on the tour for three years, then became the Chicago contact for booking blues musicians for the tour.

Toward the end of the 1960s soul music eclipsed the blues in black record sales. Chess Records’ last major hit was Koko Taylor’s 1966 recording of Willie Dixon’s “Wang Dang Doodle.” Many prominent bluesmen had died, including Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter, and J.B. Lenoir. Chess Records was sold in 1969 and Dixon recorded his last session for the label in 1970.

The many cover versions of his songs by the rock bands of the 1960s enhanced Dixon’s reputation as a certified blues legend. He revived his career as a performer by forming the Chicago Blues All-Stars in 1969. The group’s original lineup included Johnny Shines on guitar and vocals, Sunnyland Slim on piano, Walter “Shakey” Horton on harmonica, Clifton James on drums, and Dixon on bass and vocals.

Throughout the 1970s Dixon continued to write new songs, record other artists, and release his own performances on his own Yambo label. Two albums, “Catalyst,” in 1973 and “What’s Happened to My Blues?” in 1977, received Grammy nominations. His busy performing schedule kept him on the road in the United States and abroad for six months out of the year until 1977, when his diabetes worsened and caused him to be hospitalized. He lost a foot from the disease but, after a period of recuperation, continued performing into the next decade.

Dixon resumed touring and regrouped the Chicago Blues All-Stars in the early 1980s. A 1983 live recording from the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland resulted in another Grammy nomination. In the 1980s, Dixon established the Blues Heaven Foundation, a nonprofit organization providing scholarship awards and musical instruments to poorly funded schools. Blues Heaven also offers assistance to indigent blues musicians and helps them secure the rights to their songs. Ever active in protecting his own copyrights, Dixon himself reached an out-of-court settlement in 1987 over the similarity of Led Zeppelin’s 1969 hit “Whole Lotta Love” to his own “You Need Love.”

Dixon’s final two albums were well received, with the 1988 album “Hidden Charms” winning a Grammy Award for best traditional blues recording. In 1989 he recorded the soundtrack for the film “Ginger Ale Afternoon,” which also was nominated for a Grammy.

When Dixon died in 1992 at the age of 76, the music world lost one of its foremost blues composers and performers. From his musical roots in the Mississippi Delta and Chicago, Dixon created a body of work that reflected the changing times in which he lived.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwL_wohIEMw

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos