Oliver Nelson arrived in New York City in 1959, a time and place that produced seminal albums in the history of modern jazz, among them Kind of Blue by Miles Davis and The Shape of Jazz to Come by Ornette Coleman, who made his debut in the city that same year.

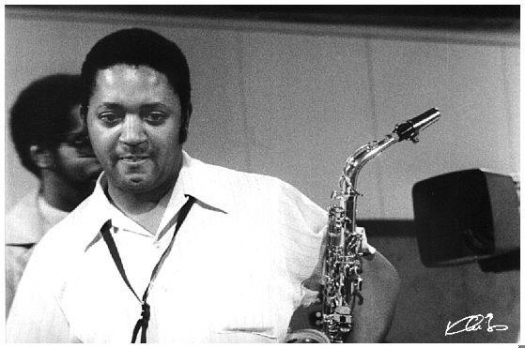

Those tectonic shifts in the art of jazz composition and improvisation had a huge impact on the jazz community and did not escape the 27-year old Nelson, who recalled: “As a player, I became aware of some things that I knew existed, but I was afraid to see them as they really were. When I arrived on the New York scene in March 1959 I believed I had my own musical identity, but before long everything got turned around and I began a period of self-searching.” Nelson got signed to Prestige Records and made a number of albums with the label in 1959 and 1960, when he was approached by Creed Taylor, who was running the then-new Impulse Records label. The first four releases from the label by J.J. Johnson, Kai Winding, Ray Charles and Gil Evans were all successful, and expectations were high for the next release. Taylor saw something in Oliver Nelson: “He was very special – melodic. He understood voicing like nobody else. There was something about him at that point. He could blend in with a section, but at the same time he had a sound that was so strident. When he played a solo he was unmistakably Oliver Nelson.” But what Creed Taylor got was much more than a fine tenor player, as Nelson focused on composition and arrangement for his recording debut at Impulse. The result was one of the most memorable jazz albums of the early 1960s, combining a star lineup with some of the best jazz arrangements on record, the unique The Blues and the Abstract Truth.

One of the musical projects Oliver Nelson was involved with before the recording of the album was playing tenor sax in Quincy Jones’ big band. The arrangements Jones wrote for that band influenced Nelson, who learned how to write arrangements that made a small big band sound much bigger. The first track on The Blues and the Abstract Truth and the most memorable on the album, Stolen Moments, is a good example.

Trumpet player Freddie Hubbard remembers Nelson’s skills as an arranger: “He got some voicings, man, that were out of this world! Like when he did (sings Stolen Moments), he had the baritone up above the tenor. To have a baritone voiced that high is unusual. And he had the alto below the tenor, and he had me playing the lead.” The tune is made out of three melodic ideas weaved together masterfully. Many compared it stylistically to Kind of Blue and there is definitely a resemblance in the overall mood. The participation of Bill Evans on piano and Paul Chambers on bass, both Kind of Blue alumni, may have something to do with it. Great solos here by Freddie Hubbard, Eric Dolphy on flute, Oliver Nelson on tenor and Bill Evans.

The second piece on the album is Hoe-Down, with an Aaron Copeland-like opening statement that seemed out of place not only to listeners and critics, but also for the musicians on the session. Freddie Hubbard: “I said, Man, what is this song? To me it was kind of out of context, but he took a lick that I had stolen from Trane and he put that on the bridge. He built it off that line. Oliver wasn’t so much of a soloist as he was a writer, so he would take bits and parts of people’s stuff.”

Cascades started out as a saxophone exercise Nelson composed in school. Again interesting writing for the horn parts and another great solo by Freddie Hubbard. Nelson writes in the liner notes: “Freddie begins his solo with long melodic lines that weave in and out of the harmonic progressions. He sounds to me like John Coltrane playing trumpet.”

The clever name Creed Taylor picked up for the album is quiet a good one, as Oliver Nelson is continually experimenting with the blues form on each track. Yearnin’ is another fine example of Nelson’s take on the well-worn structure of the blues: “Yearnin’ is a blues in C major with only superficial modifications. Pianist Bill Evans begins with two choruses of blues which set the mood of the piece. The first ensemble is 16 measures long. The second ensemble, 12 measures in length, employs a kind of ‘amen’ cadence that is different from the liturgical one in that it is stationary and does not move when the harmonic progression is resolved.” Reviewing the album for Down Beat magazine on 21 December, 1961, critic Don DeMicheal had this to say: “Nelson’s playing is like his writing: thoughtful, unhackneyed, and well-constructed. Hubbard steals the solo honors with some of his best playing on record. Dolphy gets off some good solos too, his most interesting one on Yearnin’.”

The only musician who did not take any solo during the session is baritone sax player George Barrow, who did a great job making the ensemble sound so rich. Oliver Nelson gave him his due credit in the last paragraph in the liner notes: “I take off my cap to Paul Chambers, Eric Dolphy, Roy Haynes, Freddie Hubbard and Bill Evans for the fine talent they displayed, and especially to George Barrow, who played only a supporting role. His baritone parts were executed with such fine precision and devotion that I find it necessary to make special mention of his fine work.”

My curiosity piqued by that lineup and I was wondering what kind of impact six musicians of that caliber had on the jazz music scene in the weeks surrounding that milestone recording. 1961 was amid the golden age of jazz with a hectic activity by labels and studios bringing about recording sessions for jazz musicians, so I expected to see significant participation by these high profile musicians. But what I found was even more astounding. Outside of their busy live performance schedule, during the short period before and after the recording of The Blues and The Abstract Truth, the musicians on that session either led or participated in the following albums, and this is not an exhaustive list:

December 21, 1960: Eric Dolphy and Roy Haynes, session for Far Cry by Eric Dolphy and Booker Little, on Prestige

December 21, 1960: Freddie Hubbard, session for Ornette Coleman Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation, on Atlantic

January 15, 1961: Paul Chambers, session for Whistle Stop by Kenny Dorham, on Blue Note

February 2, 1961: The Bill Evans Trio with Scott LaFarro and Paul Motian, session for Explorations on Riverside (the last studio recording by that legendary trio)

February 2, 1961: Paul Chambers, session for Together! by Elvin Jones and Philly Joe Jones album, on Atlantic

February 21, 1961: Bill Evans, session for his collaboration with Cannonball Adderley for Know What I Mean, on Riverside

February 22, 1961 (a day before the recording of The Blues and the Abstract Truth): Eric Dolphy, session for Straight Ahead by Abbey Lincoln, on Candid

March 1, 1961: Oliver Nelson, Eric Dolphy and Roy Haynes, session for Straight Ahead by Oliver Nelson, on Prestige

March 7, 20, 21, 1961: Paul Chambers, session for Someday My Prince Will Come by Miles Davis, on Columbia

March 26, 1961: Paul Chambers, session for Workout by Hank Mobley, on Blue Note

April 9, 1961: Freddie Hubbard, session for his Hub Cap album, on Blue Note

Creed Taylor’s expertise was in making jazz musicians cross over to wider audiences, as was his focus when he worked for Verve and later with his own label CTI. Artists such as Stan Getz, Wes Montgomery, Jimmy Smith and even the shy Bill Evans saw great success under his productions for Verve. Even though he did not get involved much in the studio and let the ensemble do its thing, his role in realizing The Blues and the Abstract Truth was critical to its success. Taylor later said of Oliver Nelson: “Oliver was very animated. He wouldn’t just give the downbeat or count the band off, he would leave the floor! Jump up in the air and come down right on the down beat. I’m sure his blood pressure went through the ceiling every time he conducted or played. I don’t mean out of control, but he just felt every ounce of what was happening.” The interesting photo and design on the album cover are by Pete Turner, who went on to work with Creed Taylor when the producer moved to Verve and then formed his own company CTI.

Creed Taylor

The album was a career booster for Oliver Nelson. Stolen Moments became a much loved jazz standard, played by many artists and also by jazz ensembles in music schools all over the world. After the album’s release Nelson went on to work with popular jazz artists like Cannonball Adderley, Jimmy Smith and Wes Montgomery. In 1969 Nelson was invited by James Brown to arrange and conduct the Louie Bellson big band to back the singer up for his album Soul On Top. His arrangements for well-known songs like It’s a Man’s, Man’s, Man’s World work surprisingly well in this unlikely combination.

Louie Bellson said of the arranger: “Oliver knew how to write for singers as well as instrumentalists. He left a lot of holes open for James. Some arrangers write too many notes and the singer has to strive to hit all those high notes, especially with brass. But Oliver was perfect. We didn’t have to change anything at all, it went down perfectly.” and Brown summarized it as only he can: “Oliver Nelson was one of the greatest arrangers who ever lived. That man was baaaad!”

Nelson’s composing and arranging skills took him to Hollywood, where he spent the rest of his career. His wonderful arrangements grace the background behind Sonny Rollins and other soloists on the soundtrack to the movie Alfie.

Another notable movie score orchestration by Oliver Nelson is for Bernardo Bertolucci’s movie The Last Tango in Paris, this time behind Gato Barbieri.

Nelson somehow got into the niche of detective TV series and composed for many early 1970s shows including Columbo, Ironside, Banacheck and no less than the Six Million Dollar Man.

Nelson died young at the age of 43 in 1975, leaving behind a great body of work as composer and arranger. Many still remember him for one album, the Blues and The Abstract Truth. I will let Nelson end the article with his summary of the pivotal role the album had in his career: “It was not until this LP was recorded that I finally had broken through and realized that I would have to be true to myself, to play and write what I think is vital, and most of all, to find my own personality and identity. This does not mean that a musician should reject and shut things out. It means that he should learn, listen, absorb and grow but retain all the things that comprise the identity of the individual himself.”

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos