On the evening of November 17, 1959 Ornette Coleman’s quartet took the tiny stage at the Five Spot Cafe in the Bowery neighborhood of New York City. This was the quartet’s debut at the big apple and there was a buzz around the new and strange music the band brought from the west coast.

Their first album on the Atlantic Records label was just released and landed them a two weeks residence at the club. The audience included some of the city’s most prominent musicians including Leonard Bernstein, Miles Davis and John Coltrane. Talk about intimidation. But the 29-year old Coleman and his young band were not deterred and played a set that none of the esteemed folks in the audience was prepared for. They knew they were coming to hear something different, but the band’s divergence from anything that resembled the conventions of jazz at the time shocked them. The buzz continued and the band’s engagement at the club was extended to 10 weeks. That first album on Atlantic, appropriately named The Shape of Jazz to Come, includes one of the my all time favorite pieces of music, the soulful Lonely Woman.

Don Cherry with Ornette Coleman

Few events in the history of music equaled the uproar that ensued following Ornette Coleman’s quartet performances during their engagement at the Five Spot Cafe. Stravinsky’s 1913 premiere of the Rite Of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris and Bob Dylan’s electric set at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 come to mind. But unlike those events there was no booing at the Five Spot. Some of the folks in the audience, all of the them familiar with the language of jazz, simply did not get what was going on on stage. The backlash took place in the printed media and various jazz publications. Sadly, most of the negative criticism came from fellow musicians. Roy Eldridge: “I listened to him all kinds of ways. I listened to him high and I listened to him cold sober. I even played with him. I think he’s jiving, baby. He’s putting everybody on. They start with a nice lead-off figure, but then they go off into outer space. They diregard the chords and they play odd number of bars. I can’t follow them. I even listened to him with Paul Chambers, Miles Davis’ bass player. ‘You’re younger than me’, I said to him. ‘Can you follow Ornette?’ Paul said he couldn’t either.” Red Garland: “Nothing’s happening. I wouldn’t mind if he was serious. I like to see a struggling cat get a break, but Coleman is faking. He’s being very unfair to the public. What surprises me is that he fooled someone like John Lewis.” (more on John Lewis below) Quincy Jones in a Downbeat blindfold test, in 1961: “If that’s liberty, boy, they’re making an ass out of Abraham Lincoln”. Coleman Hawkins summed it up: “I think he needs seasoning. A lot of seasoning.”

Charlie Haden

Other musicians evaluated Coleman more sympathetically even though they did not understand him. Miles Davis: “I like Ornette, because he doesn’t play cliches. Hell, just listen to what he writes and how he plays. If you’re talking psychologically, the man’s all screwed up inside.” I like Art Farmer’s review of Ornette’s Something Else album. Farmer played alternate sets to Ornette during his Five Spot residency as part of the Art Farmer/Benny Golson Jazztet. On one hand he writes: “Ornette Coleman writes some very nice tunes., but after he plays the tune, I can’t see too much of a link between the solo and the tune itself. It doesn’t seem valid to me somehow for a man to disregard his own tunes. It’s a lack of respect. Maybe he’ll eventually get to have more respect for his own tunes.” But Farmer did not let Ornette’s deviation from the norm clutter fair judgmental: “He’s different than the others on the scene, and when people come along like that, you have to be able to evaluate them as being different. Like when I first started to listen to Monk. I could not appreciate him until I could separate him from someone like Powell or Tatum. Maybe that’s what we have to do with Coleman”. More importantly, Farmer made a mention of what for me is the most important quality that Ornette Coleman has in his music: “He does have an immense amount of feeling in his playing.”

Billy Higgins

But Ornette had some strong supporters in the musicians community. Chief among them was John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet, who in the summer of 1959 told an Italian jazz magazine about the new talent he discovered: “There are two young players I met in California – an Alto player named Ornette Coleman and a trumpet player named Don Cherry. I’ve never heard anything like them before. They’re almost like twins, they play together like I’ve never heard anybody play together. It’s not like any ensemble I have ever heard, and I can’t figure out what it’s all about yet.” Not getting it did not cloud Lewis’s foresight and he recommended the band to Nesuhi Ertegun, the main man at the Jazz department of Atlantic Records, whom the Modern Jazz Quartet was signed to. Nesuhi, one of the most egoless producers in the history of music, already had some of the best free-spirited jazz musicians on his label including John Coltrane, Charles Mingus and Jimmy Guiffre. He signed Ornette and went on to produce a total of six albums with Ornette Coleman between 1959 and 1961. John Lewis did not stop there and invited Ornette and Don Cherry to a summer class at the Lenox School of Jazz in Massachusetts, a program that blended together an amazing cast of faculty and students including Kenny Dorham, Jimmy Guiffre, Gary Mcfarland, Gunther Schuller and Steve Kuhn. The east coast buzz around Ornette started there. Just how important the relationship with Nesuhi Ertegun and Atlantic Records was to Ornette can also be viewed purely from a monetary perspective: The scholarship was paid for by Atlantic Records. The royalties from the two albums Ornette recorded that year for Atlantic (The followup album Change of the Century was recorded in October 1959) paid for the trip to New York. Those two albums sold over 25,000 copies within a year of their release. This does not sound like much, but back then if a jazz album sold 10,000 copies, the artist was an established jazz musician. For such challenging music by a virtually unknown artist this was spectacular.

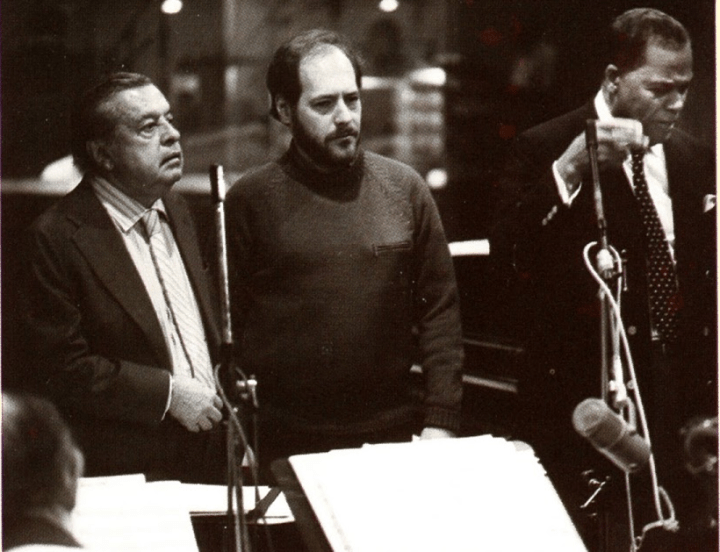

Nesuhi Ertegun (Left), John Lewis (right)

The Five Spot Cafe was a perfect place to host the Ornette Coleman Quartet. It opened its doors to jazz music at the end of 1956 and the tone was set by having Cecil Taylor’s band on opening night. The cafe attracted a colorful artist community who moved to the Bowery neighborhood due to its cheap rental prices compared to its adjacent area of Greenwich Village. Writers such as Norman Mailer, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg used to hang around, and abstract painters like Willem De Kooning and Franz Kline really liked the music they heard. Dissonance and broken rhythms did not scare them away, they saw it as abstract as their art. The club’s prestige grew considerably after a six-month residency by the Thelonious Monk quartet with John Coltrane in the second part of 1957. This was Monk’s first major exposure in New York after his cabaret card was restored, and Coltrane kicked his habit during that period. When Ornette appeared on the scene, his music may have caused the same effect as Jackson Pollock’s paintings, to many an infantile splatter of color with no art behind it. But the abstract painters got it and were mostly supportive of Coleman. Thomas Pynchon captured the scene perfectly in his book V from 1963, where a character named McClintic Sphere, an alto sax player in a jazz band, plays at a club called the V-Note and travels to Lenox, Massachusetts. His club performance is described: “The group on the stand had no piano: it was bass, drums, McClintic and a boy he had found in the Ozarks who blew a natural horn in F”, the audience is “mostly those who wrote for Downbeat magazine or the liners of LP records…”, and the priceless sentence: “‘He plays all the notes Bird missed’, somebody whispered”.

Five Spot Safe

Contrary to his harsh critics’ belief, Ornette Coleman was well versed in the music that preceded him and could play Bebop with the best of them. In his youth he listened carefully to Charlie Parker and practiced the concept of improvising over chord progressions and rhythm changes. He just found that concept restrictive and instinctively departed from it. Martin Williams, who wrote the liner notes to The Shape Of Jazz To Come, was at the Five Spot and observed Coleman’s skill: “and suddenly Ornette Coleman up on the bandstand in the Five Spot during a blizzard started to play the blues like Charlie Parker. And I have never heard anyone else other than Charlie Parker do that that way, and Charlie Parker has many followers and imitators. None of them has come near this. Ornette had the attack on the reed right. He was doing it like the late Parker, the more virtuoso period of Parker’s short career. He was absolutely uncanny and he went on and on doing it. And I said “Man, why don’t you do this more often? Why don’t you do his on record to show people that you really do know what you are doing?” And Ornette said something like “Oh, I like to do that every now and then for fun” and dismissed it that way.” Buell Neidlinger, who played bass with Cecil Taylor at the Five Spot in late 1956 and kept frequenting the establishment as a listener, remembered another episode: “It was a unique bandstand because right in front of it was the hallway to the kitchen. I heard some amazing shit in the hallway. They had an old record player up on a shelf and that’s what they played their intermission music on. One night, Ornette Coleman was working there; I worked opposite Ornette for six months with Jimmy Giuffre there. They were playing this Charlie Parker record; I knew those records by heart. I heard this weird effect as though Charlie Parker had come to life. It was Ornette standing there playing along with the record, so much like Bird that it was uncanny.”

Ornette Coleman at the Five Spot

Ornette’s tendency to go off while playing music to a land familiar only to himself was not a new thing for him. Back in the late 1940s, when he was about 20 years old, he could scare people away from a jam session with his style. Trumpeter Bobby Bradford, who would later play with Coleman in 1971 on the albums Science Fiction and Broken Shadows, performed with Coleman in the late 40s and early 50s. Familiar with bebop musicians who would play half a step above the key for one phrase just to add excitement, he said: “but Ornette would go out and stay there – he wouldn’t come back after one phrase, and this would test the listener’s capacity for accepting dissonance.” Coleman got malevolent glares everywhere he went, be it his home state of Texas, New Orleans or California. He expected New York City to be different, being the jazz capital of the world. But it was no so: “When I arrived in New York… from most of the jazz musicians, all I got was a wall of hostility… I guess it’s pretty shocking to hear someone like me come on the scene when they’re already comfortable in Charlie Parker’s language. They figure that now they may have to learn something else”. Bebop was a huge musical innovation in the mid 1940s, but after a decade and a half many musicians got into a comfort zone with the style and used it to coast through its familiar chord changes and harmonic progression. Bebop offered a map to musicians who met for the first time and wanted to jam together. But Ornette feels music differently: “My music doesn’t have any real time, no metric time. It has time, but not in the sense that you can time it. It’s more like breathing – a natural, free time. I like spread rhythm, rhythm that has a lot of freedom in it, rather than the more conventional, netted rhythm. With spread rhythm you might tap your feet awhile, then stop, then start tapping again.” For most folks in a jam session, that viewpoint would be enough to boot him off stage.

Ornette Coleman

Gunther Schuller, who was on the faculty of the Lenox Jazz School and taught Coleman during the summer of 1959, observed: “His musical inspiration operates in a world uncluttered by conventional bar lines, conventional chord changes and conventional ways of blowing or fingering the saxophone. Such practical ‘limitations’ do not seem even to have been overcome in his music – they somehow never existed for him. I don’t think that Ornette could ever play at playing as so many jazzmen do. The music sits too deeply in him for that.” The reality is, if Coleman were to step into a random jazz jam session today, he would most likely be kicked off the stage as fast as he was more than 70 years ago. Even though he influenced an amazing array of free jazz musicians in the 1960s and beyond, an overwhelming number of jazz players would find it difficult still to this date to jam with him. Plus what’s with that white plastic saxophone that looks like a toy? A broke Ornette Coleman bought the plastic horn in Los Angeles in 1954 because it was cheap. At the beginning he did not like it, but then he found new qualities in it: “The plastic horn is better for me because it responds more completely to the way I blow into it. There’s less resistance than from metal. Also, the notes seem to come out detached, almost like you could see them. The notes from a metal instrument include the sounds metal itself makes when it vibrates. The notes from a plastic horn are purer.”

Ornette with the plastic sax

Ornette Coleman’s music has been recorded by many artists over the years, and one of the best groups to interpret his songs was Old and New Dreams. Perhaps they were best qualified for the job because they were simply part of Ornette’s bands at various stages in the late 50s and 60s. Don Cherry and Charlie Haden were part of the quartet that recorded the first Atlantic albums and played at the Five Spot. Ed Blackwell on drums replaced Billy Higgins who in 1960 lost his cabaret card. Dewey Redman on Tenor sax knew Ornette since childhood and joined his group in the late 60s. Between these guys you have a decent chunk of the best in jazz covered, and the list of amazing recordings featuring them is too long to start listing. Old and New Dreams was formed with the mission to play the music of Ornette with the same spirit and intensity they played it with the maestro. Blackwell recalls the gigs at the Five Spot: “During this time most of the clubs were featuring two bands a night. There would be four sets. Ornette would play two sets and the visiting band would play two sets. This was going on for like six nights a week. We had a chance really to stretch out during our sets. Sometimes Ornette would stretch out our set, and sometimes he would just cut them a little shorter, depending on what mood he was in. But it was always intense. A lot of times we would rehearse all day and then come to work that night, and everybody was always geared up to play. The energy that flowed through that band was phenomenal.” Outside of Ornette Coleman’s version of Lonely Woman, Old and New Dreams’ interpretation of the piece from their 1979 album on the ECM label is my favorite. The opening of the tune is one of my favorite of any piece of music, and the sensation that Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell create with their rhythms is a joy to listen to. Haden said simply of his role with the original quartet: “With Ornette, there was no piano, but I became the piano.”

As Art Farmer was sensitive enough to recognize, all the innovations Ornette Coleman brought to the world of jazz composition and improvisation are secondary to me compared to the emotion and feeling he expresses in his playing. Many things grab you in a song such as Lonely Woman – its melancholy mood, the unexpected ways in which the melody moves, the interplay between the sax and trumpet. But it is the way that Ornette phrases the melody and improvises on it that truly communicate what is behind the title of the song. In a 1997 interview with Jacques Derrida Ornette talked about the origin of the title: “Before becoming known as a musician, when I worked in a big department store, one day, during my lunch break, I came across a gallery where someone had painted a very rich white woman who had absolutely everything that you could desire in life, and she had the most solitary expression in the world. I had never been confronted with such solitude, and when I got back home, I wrote a piece that I called Lonely Woman.” Here it is, from the Shape of Jazz To Come, 1959:

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos