Duke Ellington was among the preeminent American composers of the 20th century, and the most exhaustively studied of all jazz artists. There are more books and articles about him than any other jazz musician, and collectors have pored over his vast discography — not just a prolific half-century studio output but also hundreds of hours of radio broadcasts, audience tapes, and film and television appearances.

It might seem, then, that there couldn’t possibly be much Ellingtonia left uncharted. But here is a major find — an eight-minute recording that you’ve almost certainly never heard. It’s the oldest surviving Duke Ellington radio broadcast, known only to a small handful of connoisseurs and never made available to the public.

This broadcast emanated from the Publix Allyn Theatre in Hartford, Conn., from 11:45 p.m. to midnight on April 11, 1932. It was recorded off the radio — WTIC, now an AM news and talk station — using a disc recorder. This precedes by four years the next-earliest Ellington airchecks, from the Congress Hotel in Chicago on May 9 and 26, 1936.

How Ellington was recorded off the air in ‘32, and where that disc has been for the last 86 years, is a fascinating story. But it’s just one facet of what we’ll unpack in this installment of Deep Dive.

Before we take the plunge, it’s important to acknowledge Steven Lasker, a jazz historian who has won two Grammy awards as a reissue co-producer, notably in 1999 for The Duke Ellington Centennial Edition – The Complete RCA Victor Recordings (1927-1973). He has ample experience remastering old recordings for that and other reissues, and did the best possible job of cleaning up and optimizing the sound of the track.

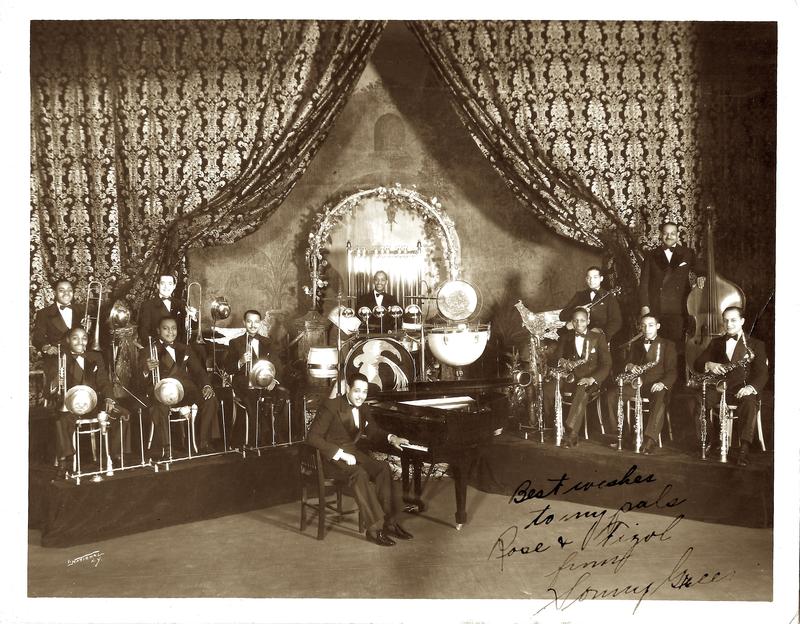

Steven has asked me to convey his joy and relief at finding a suitable outlet to share this historic document, which he believes to be the earliest surviving broadcast by an African-American jazz band recorded off the airwaves, and the second-earliest surviving broadcast of any type by such a band.

The first known example, by Cab Calloway on April 21, 1931, is a “line transcription.” That is, rather than being recorded off the radio, it was recorded onto discs by RCA Victor from an NBC line direct from the floor of the Cotton Club. This was issued in 2003 on Bear Family records, Live From the Cotton Club, a 2-CD set with a hardcover book. (The book mentions that it was likely broadcast over German radio in September 1931 — so although it was recorded “live,” it wasn’t broadcast until months later.)

But that’s not the only historically significant aspect of our aircheck from Hartford. The longest item of the broadcast, “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” is a song far better associated with Louis Armstrong. It was only recorded by Ellington three decades later, in a different arrangement, for an LP wistfully titled Will Big Bands Ever Come Back?

So to truly understand the significance of our find, we’ll need to delve into the history of that song, the circumstances around the broadcast, and the twisty provenance of this recording as a physical object. First let’s listen again and consider what we hear.

First, you’ll notice an announcer speaking over the music, and naming the theater in Hartford where Duke’s “nationally famous dance band” would appear through Thursday. While he speaks, the band performs Ellington’s theme song at the time, “East St. Louis Toodle-O” (later spelled with two O’s).

The announcer mentions that “at the conclusion of the signature number, you’ll hear…‘The Duke Steps Out’” (Duke had recorded this in 1929) — but at this point, 39 seconds in, the person recording the aircheck flipped over the disc in order to record on the other side, so that tune is missing altogether here.

At 0:40 the band goes into “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South.” Ellington performed the song for broadcast at other times, but this arrangement was never preserved anywhere else. And it has many nice touches, starting with a grand introduction. At 1:14 the brass play a staccato triplet, echoed by the drums at 1:33.

At 2:07 Ellington provides a few seconds of piano interlude, freely and out of tempo, to introduce a clarinet solo. The clarinetist, Barney Bigard, is accompanied only by the rhythm section, so it’s a great opportunity to hear what piano and bass are doing.

Then Sonny Greer, the band’s drummer, sings the famous lyric. In the early days Greer sang on the occasional Ellington number, though this sounds different because it’s quite high in his range. (It resembles his vocal on “Dinah,” recorded with Duke in February 1932.) At 4:47 the full band returns, and the clarinet continues to be featured, including trills starting at 4:54. Bigard gets a break to himself at 5:39.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KdkqZkLvTd8&feature=youtu.be

At 6:02, there’s a surprise for those who know their Ellington: The band plays the theme of “Lazy Rhapsody.” At the bridge (6:30), it goes into a dramatic passage somewhat like the later “Echoes of Harlem,” with Greer capping it on orchestral tubular bells. The announcer says “Time for one more, going to be ‘Double Check Stomp.’” Duke had recorded this three times in 1930, featuring different soloists each time.

Ellington was constantly rethinking pieces, so that they often sounded different from one recording session to the next. In keeping with that spirit, this version of “Double Check Stop” has several unique aspects. First, Duke plays the intro, formerly for full band, by himself on solo piano. After the bass solo, also found on the 1930 versions, Freddie Jenkins plays a trumpet solo not found on the studio versions. He quotes the opera Pagliacci at 7:46, as Armstrong liked to do, and at very end, he plays sequences of three fast eighth notes, a ragtime standby.

Let’s return for a moment to “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” which was written for a Los Angeles theatrical production titled Under a Virginia Moon, in June 1930. The star of that show was Dulce Cooper, but today the more familiar name is her love interest, Randolph Scott, who went on to a long film career. He wasn’t yet a star, and didn’t receive any billing in ads.

A review from the time notes: “Miss Dulcie Cooper, who plays the daughter, and Randolph Scott are sitting on the steps holding hands when they break into the refrain of ‘Sleepy Time Down South.’ It is taken up and sung to excellent effect, by Clarence Muse in the person of Jackson, the Negro servant.” (Muse, the other best-known name in the cast today, was a well-respected actor, writer and director who became a pioneer of film roles for black actors.)

According to copyright records, the cover of the original sheet music from 1931 shows the title as “Sleepy Time Down South,” and the song is described as a “syncopated spiritual.” The song is credited as follows: Words and Music by Leon Rene, Otis Rene and Clarence Muse. But this doesn’t tell us who did what. The Rene brothers appear to have been musicians, and Muse, who was co-credited on a few other songs, seems to have been a lyricist as well as, at times, a composer of melodies. That Muse was probably involved here as more than a lyricist is suggested by a 1979 interview in which he says of “Sleepy Time” (at 43:54) that the song “was born in 15 minutes.”

Mildred Bailey recorded the song twice before the end of 1931, and the most commonly known early sheet music bears her likeness. It’s nice to think that in performing the song, Ellington was toasting Armstrong. But at the time Bailey was more closely associated with the song.

So how did Duke get connected with “Sleepy Time,” precisely? Lasker points out that the Ellington band was in California in Aug. 1930, filming the movie Check and Double Check at RKO and staying at the Dunbar Hotel. It’s possible that the Rene brothers plugged the song to Ellington that month. The Rene family did recall pitching the song to Armstrong at a dinner with Les Hite and others that must have taken place that fall.

Sonny Greer told the pianist and Ellington expert Brooks Kerr that he was the first to sing “Sleepy Time” (and, incidentally, “Star Dust”) over the airwaves, before Armstrong. But NBC Radio logs of Ellington’s Cotton Club broadcasts between Sept. 29, 1930 and Feb. 3, 1931 omit any mention of “Sleepy Time,” so that claim can’t be verified.

On the April 11 aircheck from Hartford, we hear more than just a pass through “Sleepy Time.” After that extended solo by Bigard, the key and chord progression stay the same while the band goes into a bit of “Lazy Rhapsody.”

Duke had recorded “Lazy Rhapsody” in the studio for the first and only time on Feb. 2. I suppose that the word “Lazy” was Duke’s witty way of indicating that this was a song based on “Sleepy Time,” as the British swing composer Spike Hughes correctly noted at the time.

By segueing from one song into the other, Duke makes the connection explicit, in a way that he apparently did not continue to do — and in a way that radio listeners would not “get,” because the Brunswick record, titled “Swanee Rhapsody,” was not to be released until May 5, 1932. (The record company’s notes at first gave the title as “Lullaby,” later changed to “Lazy Rhapsody,” and then to “Swanee Rhapsody,” which appeared on some original 78 labels).

Bigard is quoted discussing the similarities between “Lazy Rhapsody” and yet another song, the popular standard “Moonglow” (written this way on the sheet music, but sometimes written as two words) in Stanley Dance’s book The World of Duke Ellington: All composers borrow from one another. That’s nothing new, so long as they don’t go too far. [Take] over eight bars of anybody’s song, and there’s likely to be trouble. You take “Moon Glow.” That was taken from “Lazy Rhapsody,” and I believe Mills arranged a big settlement with Duke over that.

Irving Mills was Duke’s manager and music publisher from 1926 to 1939, and working with him meant that Mills was credited as coauthor on many songs, including “Moonglow”— not an unusual business arrangement for the time. (Besides Mills, it was credited to musician Will Hudson and lyricist Eddie DeLange.) “Moonglow,” even before it was published in January 1934, was something of a hit, like “Sleepy Time” before it. If you’re a movie buff, you might recall its delightful use in this dance scene from Picnic.

Both songs turn up about 600 times in Tom Lord’s master discography of jazz, and this count omits many versions by pop artists. For “Sleepy Time,” the count includes many short versions by Armstrong, who used it as his theme song from 1931 until his death.

The sequence of events around “Sleepy Time” reveals a lot about how the music business used to work. Someone writes a song, then tries to get artists — in this case Ellington, then Armstrong — interested in recording and performing it. A publishing deal is arranged, and the sheet music becomes available. That publication is circulated widely and aggressively by “song pluggers” to get the song recorded quickly and frequently, hoping for a “hit.” In addition, the publisher might be affiliated with a recording company.

Finally, one artist after another records the song: first Armstrong in this case, then clarinetist Jimmy Noone, then two versions by Mildred Bailey, even a recording from London, and more. It’s no wonder that Ellington tried his hand at it, though, for whatever reason, he never recorded it.

We’re lucky to have his version. So how did we get it?

Larry Altpeter isn’t a name widely known even to the most devoted connoisseurs of the swing era, but he had a successful journeyman career. A trombonist who first recorded with bandleader Paul Specht, sometimes as “The Georgians,” from 1928-31, he continued to work with a variety of groups — among them Louis Prima (in ’35); singers Chick Bullock, Bea Wain, and a vocal group called the Smoothies; and studio orchestras accompanying the likes of Sarah Vaughan (1952) and Tony Bennett (1956).

On this version of Prima’s “Put on an Old Pair of Shoes,” Altpeter takes a nice solo at about the minute-and-a-half mark. He is also just barely visible in a 1936 film of Freddie Rich’s band, featuring trombonist-comedian Jerry Colonna and trumpeter Bunny Berigan. That’s him at the left end of the brass section.

One more thing we know about Larry Altpeter is that he must have been an audio hobbyist. We’re talking about him because he was the one who recorded Ellington’s broadcast from Hartford in 1932, using a disc recorder. Remember that broadcasting technologies were strictly designed for transmission, without a moment’s thought given to preservation.

Radio shows only survived if the station recorded them for later broadcast, or if a listener had a means of recording it at home (which wasn’t common until the advent of reel-to-reel tape — which, while invented in Germany around 1936, wasn’t readily available in the United States until the ‘50s). Still, home disc recorders, while rare, were available at that time.

The original medium for our Ellington aircheck is a ten-inch diameter blank “RCA Victor Home Recording Record.” It was recorded on an RCA Home Recording Electrola, first advertised in the Oct. 1930 issue of Talking Machine World. The Electrola used a “Special RCA Victor Home Recording Needle” to mechanically etch and reproduce sound modulations in a guide groove pressed onto each of the disc’s two sides. These discs are made of a semi-flexible, plastic-like substance the company called “Victrolac.”

Here are some images of an Electrola from 1930, the RAE-57. Altpeter used the model introduced in late 1931, the RAE-59. Visually similar to the model 57, it crucially had the capacity to record at 33 and 1/3 r.p.m.

The slower speed capability was added in anticipation of Victor’s soon-to-be introduced “Long-Playing Record,” or “Program Transcription,” as they were described on their labels. Yes, this was 33 and 1/3, some 17 years before Columbia Records introduced its “long playing” record, a.k.a. the LP. (The history of science is filled with thousands of inventions that surfaced again years later — or didn’t, such as 16 r.p.m. super-long-play recordings, a few of which were made in the ‘50s.)

An aside: Ellington made two recordings at 33 1/3, both medleys, in 1932. Because simultaneous recordings were made from two locations in the room that day, these two medleys have been issued in stereo, though they weren’t conceived of in that way. (Steven Lasker and his fellow researcher Brad Kay made this discovery in 1981.)

Altpeter recorded the aircheck with no apparent motive beyond personal enthusiasm. The disc sat in his home for some 60 years — until the bassist and bandleader Vince Giordano, an early-jazz specialist, found out about it. As Vince told me, he got a call in the early 1990s from David Sager, a fine trombonist and noted early-jazz expert who works at the Recorded Sound Research Center at the Library of Congress. (David is also a graduate of my M.A. program in jazz history at Rutgers-Newark.)

David Sager’s uncle was the bandleader and violinist Nat Brusiloff. The trombonist in Brusiloff’s band was Larry Altpeter. Sager informed Giordano that Altpeter had recorded music off the radio in the 1930s. As Vince recalls: I called Altpeter and went down to his unfinished basement crawlspace and saw 50 or so RCA Home Recording discs he had recorded off the air in an old soda box. They had no sleeves and there was lots of dust, dirt and sand on them. I asked what he wanted for them, he refused to take any money: “Just take them and enjoy them.” When I brought them home and cleaned them and tried to play them — there was hardly any sound! What I didn’t know was, they needed a special, very large phonograph needle to play them and get the music out of the grooves. I had no idea what was on these records — the labels sometimes had very little handwritten info. The other 50 discs were a mixed bag of Boswell Sisters, a Cab Calloway disc, and some other hot music from the early 1930s.

Word of the Ellington disc started to get out. It was first mentioned by John Hasse in his 1993 bio Beyond Category: The Life And Genius Of Duke Ellington. It was then listed in a discography by W. E. Timner, The Recorded Music of Duke Ellington and His Sidemen (Fourth Edition, Scarecrow Press) in 1996. Since then it has been mentioned in other discographies, though few people had heard it.

In 1998, Giordano was working for the BMG archive (which included RCA). There he met Lasker, who was co-producing the Duke Ellington RCA boxed set. Steven purchased the Ellington disk from Vince, and has since played it for a few Ellington specialists. But even though he’s often consulted for Ellington reissue projects, there hasn’t been an appropriate format in which to present the broadcast properly.

What do we learn from these eight minutes of raw broadcast footage from 1932? On the most basic level, this recording gives us new information about one of our most significant composers and his band at a fast-moving point in their development.

In his early years — especially from roughly 1928 to 1932, the period we’re studying here — Duke was expected to record and perform pop songs by others, especially if the songwriter and/or sheet music publisher had connections to his manager, or to the record label. That’s why you find him recording “That Lindy Hop” in 1930, for example.

This was typical of the music business. For example, on Billie Holiday’s recordings in 1935, with pianist Teddy Wilson, they recorded mostly newly written songs that were not of their own choosing. But artists of this caliber bring much to that situation, and Duke certainly brought his imagination on “Sleepy Time,” even if he never got around to recording this version for commercial release.

During the time period just after this aircheck, Ellington enjoyed more independence, regularly composing and releasing his own hit songs. “Sophisticated Lady” was first recorded in 1933; “Solitude” in Jan. 1934; “In a Sentimental Mood” in April 1935; and “Prelude to a Kiss” in 1938. All of these — and later gems, many of those composed with Billy Strayhorn, whom he met at the end of ‘38 — have remained part of the American consciousness. (They were often instrumentals at first, with lyrics added later.)

I hope we’ve illustrated the many reasons that a newly discovered Ellington item is exciting. It’s not only a chance to hear some new music by the maestro, but it also enables us to make connections in time and place between other events, recordings, bands and composers of the era. No recording happens in a vacuum, and every new piece of information fits into the ever-changing puzzle that is the writing of history.

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos