21.12. – Happy Birthday !!! Paco de Lucia was one of the most admired practitioners of the flamenco guitar and credited with bringing the traditional gipsy music of southern Spain to mainstream audiences around the world.

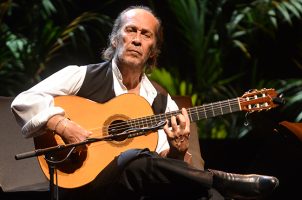

De Lucia looked every inch the traditional Spanish guitarist. One review described him as “the portrait of studied concentration and pristine perfection: stiff-backed and stern-faced, with a distinguished air about him that some might misread as haughtiness. He’s proud and majestic, like a regal Arabian steed prancing with grace and elegance, yet able to reveal great power.”

Yet de Lucia became known as the leading proponent of the “New Flamenco” style, which combines flamenco guitar virtuosity with other genres — such as jazz, rock, Cuban swing, tango and salsa. He constantly broke musical boundaries, and his career was defined by crossover collaborations with guitarists such as Eric Clapton, John McLaughlin and Al Di Meola, as well as the jazz pianist Chick Corea.

De Lucía had begun to broaden his horizons in the late 1960s, on teaming up with the charismatic young singer Camarón de la Isla. Their partnershipyielded many great recordings and signalled the arrival of the New Flamenco.

De Lucía’s rumba Entre Dos Aguas(Between Two Waters, 1973 ) became a very popular recording in Spain. Towards the end of the 70s De Lucía delivered further surprises to the flamenco world when he collaborated in an acoustic summit with the guitarists John McLaughlin and Larry Coryell – both already lauded as superstars of electric jazz fusion – known as the Guitar Trio. A later version of the trio included Al Di Meola, with whom De Lucía had collaborated on the album Elegant Gypsy (1977).

The inclusion of De Lucía’s captivating version of flamenco – completely authentic, yet open-minded – in this virtuoso and stadium-friendly context brought him new admirers worldwide.

From the 80s onwards, his own band incorporated several instruments that are “new” or unfamiliar within flamenco, such as the cajón, a box-like percussion instrument from Peru, saxophone, flute, brass, chromatic harmonica and fretless bass guitar. Yet these novel sounds are always deployed carefully and ingeniously alongside the traditional elements of palmas (handclaps), guitars and vocals.

The effect is still exhilarating and was startlingly fresh at the time, giving the emerging audience for “world music” a taste of improvised music that was far from the familiar tropes of jazz and blues. De Lucía often incorporated a dancer in his ensemble, which helped take the intensity of his performances to thrilling heights. With De Lucía there was never any sense that the audience was witnessing a heritage act – each gig, each festival spot felt newly minted, like the best music of any genre.

Yet it would be a mistake to regard what De Lucía did as “fusion”. He always stayed true to the flamenco music of his youth. It was only the context, the setting, the juxtaposition that was new. He also delighted in the flamenco guitarist’s traditional role as accompaniment – to dance, song or another guitar – and made a virtue of this element at concerts in which he was the self-effacing star attraction. This is another reason why his on-screen presence in the Carmen film was so discreetly effective.

He was born Francisco Sánchez Gomez in Algeciras, in the province of Cádiz, across the bay from Gibraltar. As an infant prodigy he was pushed into intense study of flamenco guitar by his guitarist father, who would oblige him to practise for 10 or 12 hours a day. He began playing professionally aged 12, taking the stage surname De Lucía from his Portuguese mother, Lucia Gomes; Paco, the diminutive of Francisco, was a common name in the area.

At the age of 14 he was recruited for the prestigious company of the dancer José Greco, playing on three international tours. While in the US with Greco, De Lucía encountered the flamenco master Sabicas, who gave the young guitarist advice he was to heed subsequently – that he should not copy the work of others. However, the older guitarist, like many more flamenco purists, would later criticise De Lucía’s tendency to push his music beyond the genre’s fiercely patrolled boundaries.

Occasionally in interviews De Lucía would express mild frustration with the limitations of the guitar, as to Barry Cleveland in Guitar Player magazine: “What I like best about flamenco is the singing and I might have become a singer if I had not been such a shy child. It is difficult to ‘sing’ with a guitar … it can only produce notes of very short duration.” Flamenco music is also elusive in that it has been transmitted through an oral tradition: “It is impossible to write down what is being sung because 80% of it is expression. Flaminco is a very pure music that comes from inside of you – from the blood.”

Another manifestation of his great restlessness was his performance of Joaquín Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez – a time-consuming project for someone not normally used to starting from notated music.

De Lucía’s awards ranged from a prize at an International Flamenco competition in Jerez in 1959 to the national Asturias prize for art in 2004. He won Latin Grammies in 2004 and 2012.

Among the family members who performed with De Lucía were his brothers Pepe, a singer, and Ramón (de Algeciras), a guitarist, who died in 2009. With his first wife, Casilda Varela, De Lucía had three children, and with his second, Gabriela Carrasco, he had two.

Paco de Lucía (Francisco Sánchez Gomez), guitarist and composer, born 21 December 1947; died 25 February 2014.

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos