“We’re going to play this beautiful tune by Leonard Bernstein,” says alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley at one point on Swingin’ in Seattle: Live at the Penthouse (1966-1967), a collection of previously unreleased live material. A hint of weariness creeps into his usually self-assured tone, and Joe Zawinul begins playing open, rubato chords beneath the introduction — about as far from the groovy riffs that he’s best known for as one can get.

Adderley continues: “It’s called, ‘There’s a place for us…somewhere…somewhere.’”

Much of Swingin’ in Seattle treads familiar territory: tunes that were either already established in Adderley’s repertoire, or would soon become signatures. But “Somewhere” is an outlier, despite the fact that he’d just recorded a fairly snoozy version with an orchestra.

On this live recording (whose arrangement he would laterrecreate), Adderley leans into the song’s drama and seriousness, refusing to inject the levity and humor that had long allowed him to reach a wide audience.

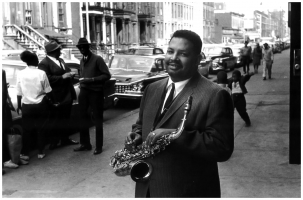

It’s a side of Cannonball that would become more important towards the end of his career, complicating many of the ways that jazz fans today sum up his body of work. The main word that people use to explain what made Cannonball Adderley special is “joy” — and they’re not wrong. His playing is bright and rich, prone to notes flooding out in a rush of genuine enthusiasm that never sounds superfluous.

But that description can also come across as dismissive. The agonizing pursuit of pure musical expression, whatever the human cost, is an enduring trope within jazz lore. Adderley doesn’t fit into that frame. His “joy” — it feels more accurate to use the French term, joie de vivre — is part of what keeps his work from being truly (ahem) canonical; he was just too content, somehow, to be taken seriously.

Yes, he was a generally happy guy, by most accounts — he had few vices aside from the zest for a good meal (the source of his original nickname, “Cannibal”). But Cannonball was also brilliant. One of the most intuitive improvisers to ever tackle the music, he played with mind-boggling technique that never obscured his ultimate intention: to reach people where they were.

Maybe that explains why Adderley made so many live recordings — why Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! Live at “The Club,” the album that crystallized his status as either an icon or a sellout, depending on who you’re talking to, was recorded at Capitol Studios in front of an audience imported to recreate one of his intimate shows. He specialized in speaking to people, literally and musically, and it’s harder to speak to people when you can’t see or hear their response.

That’s one reason why Swingin’ in Seattle: Live at the Penthouse (1966-1967), one of the debut releases from Reel to Real, a new label dedicated to resurfacing forgotten jazz performances, is such a remarkable artifact. Not only is there a little more than an hour of Cannonball Adderley and his quintet — his brother Nat Adderley on cornet, Zawinul on piano, Victor Gaskin on bass and Roy McCurdy on drums — playing vital, thoughtful music. Much of Adderley’s interstitial commentary, often cut for space in the LP era, is featured as well.

The four performances that the record pulls from, on June 15 and 22, 1966, and Oct. 6 and 13, 1967, also bookend the most successful period of Adderley’s career. In between, he and this same quintet recorded Live at “The Club,” and “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” shocked everyone by soaring up the pop and soul charts. Yet, it’s hard to definitively call those two years his peak; as the very thorough liner notes that accompany this reissue elucidate, it feels more like a turning point, as Adderley begins to edge away from the straight-ahead hard bop that had defined much of his output, and integrates groovier elements from soul, R&B and funk.

As is fitting for a band in transition, these performances show the quintet at both its glossiest and most outré, sometimes in the same song. On “The Morning of the Carnival,” the anglicized version of an Antonio Carlos Jobim tune from Black Orpheus, Cannonball and Nat begin with a reverent, smooth rendition of the melody; three minutes in, though, Cannonball is wailing, leaning into some of the screeching dissonance not often associated with his relentlessly melodic style. A gurgling quotation of “Yankee Doodle” pulls the tune into a different stratosphere.

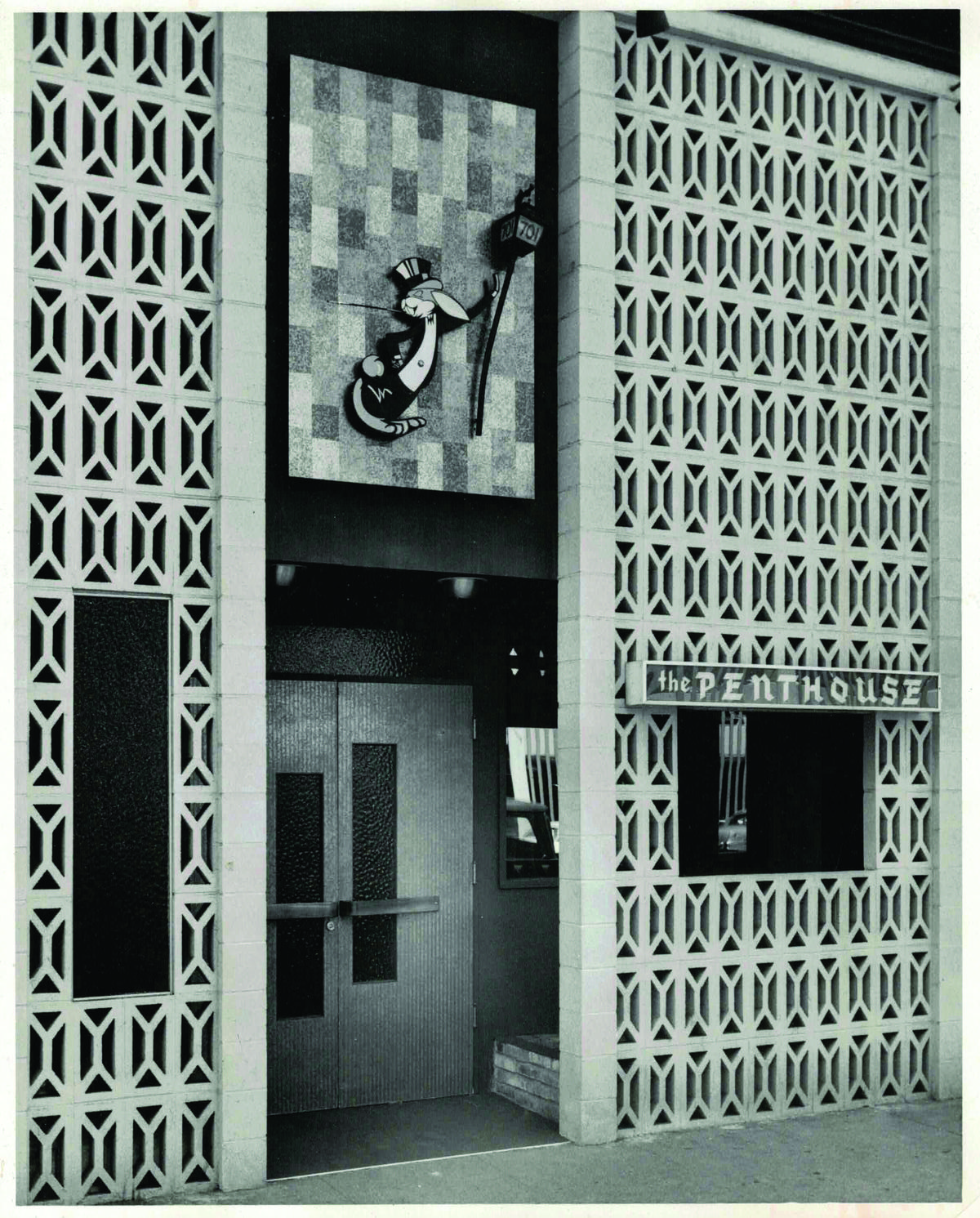

The band’s range, along with the record’s great aural ambience, is transporting, taking the listener to a jazz club called the Penthouse in downtown Seattle (the applause on the record, it should be noted, is very polite). Adderley performed there often, and Jim Wilke, a local jazz radio legend heard introducing the band on the album, broadcast live there every week on KING FM.

It was an anchor in a city that was fast becoming an unlikely hub for the music. The Penthouse had opened in 1962 — the same year the World’s Fair brought Seattle its most iconic piece of architecture, the Space Needle. Though it only lasted until ‘68, it was among the city’s first “modern jazz clubs,” as Paul de Barros put it in his book, Jackson Street After Hours: The Roots of Seattle Jazz.

The city was fully segregated at that point, like most in the United States — a fact that wouldn’t necessarily be relevant to this record, except that Adderley alludes to issues of systemic injustice during the performance. As he explains before “Somewhere,” the band had, just that afternoon, played for children being held in a King County juvenile detention center.

“It’s kind of an interesting thing, though, because a lot of kids are not sure about where they belong,” he says. “Some of us sometimes share that feeling…you know, we’re not quite convinced.”

He doesn’t explicitly mention racism, and yet one gets the same sense of concerned solidarity that makes the opening of “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” so indelible: “Sometimes we don’t know just what to do when adversity takes over.”

Of course, “Somewhere” — a centerpiece of Bernstein’s musical West Side Story, with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim — is a song about longing to escape racism. Adderley leads the haunting ballad with his usual restraint, but also draws out a reedy edge in his tone that isn’t always present — reluctant, perhaps, to make it too pretty.

The tune doesn’t get the same uproarious applause as this set’s raucous renditions of “Sticks” or “Hippodelphia” — or show the same virtuosity as the uptempo, rollicking “Big P,” which opens the album. But it shows the part of Cannonball that gets undersold when he’s only allowed to be jubilant or ebuillant or lively, or however else one might put his irrepressible energy into words.

Cannonball would only grow more outspoken over the course of his career, channeling his gifts into a series of releases that were increasingly explicit about merging art and activism. This album is a rare glimpse at what it would have been like to watch him arrive at the place where he finally felt like that was possible.

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos