Louis Armstrong has served as the focus of many works of literature. Now, a few seconds of old film that appear to feature Armstrong as a teenage boy have captivated jazz journalist James Karst.

If Karst’s theory is correct, the clip from 1915 shows Armstrong at a turning point in his early life — years before he became famous and eventually legendary around the world.

Karst tells NPR’s Scott Simon that he stumbled upon the alleged clip of Armstrong on the Getty Images website. For the first beat of the eight-second clip, apparently taken from a newsreel, pedestrians cross a busy New Orleans street in 1915. Then, the boy who Karst suspects to be a 13 or 14-year-old Armstrong enters the shot.

From there, Karst got to work piecing together bits of evidence to support his hunch. He reached out to Dr. Kurt Luther, a professor at Virginia Tech University known for his work identifying people in Civil War-era photographs, for advice, and compared the facial features of the boy in the video to those seen in the earliest known images of Armstrong. Karst also accessed census records to verify the small number of black newsboys on the New Orleans records at the time the film was taken.

At the time, Karst says, Armstrong would have recently been released from a boys’ reformatory where he had been sent for shooting a pistol into the air — this reformatory is also where Armstrong played in the marching band and received his first formal music instruction. As Karst says, after coming out of the reformatory in June of 1914, Armstrong found work as a newsboy to help support his family, who lived in poverty.

Karst says he’s been surprised to find that others largely accept his suggestion, which was published in a magazine of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. “I fully expected people to try to pick it apart.”

According to Karst, there is one evident clue on the boy’s face in the clip: “The beautiful Louis Armstrong smile that later became famous.”

he year 1915 marked a time of transition and upheaval in the life of Louis Armstrong. The New Orleans native was in his early teens, an awkward period in the life of many people. But Armstrong’s entry into adolescence was complicated by a variety of other factors specific to his situation. First and foremost was that he needed a job.

The musical prodigy had recently left the reformatory known as the Colored Waif’s Home, where he had been sent in early 1913 after being arrested for shooting a revolver into the air on New Year’s Eve. It was at the home that he supposedly received his first formal music instruction, playing cornet with the band whose local performances included marching in parades, accompanying a local theater production, and entertaining crowds at a Christmas gift giveaway for poor black children. (Even philanthropic ventures in New Orleans were segregated.)

After being released from the Waif’s Home in June 1914, Armstrong, who grew up in extreme poverty, needed to support himself and his family. He cycled through a number of menial jobs as he began to scrape together some paying gigs as a musician. Several times during this period he went back to a familiar occupation as a newsboy, even though he knew it was a dead-end career.

“At this time Louis tried earnestly but vainly to earn a living in a steady job,” writes Robert Goffin in Louis Armstrong, Le Roi du Jazz, translated into English by James F. Bezou and published under the title Horn of Plenty in 1947. (Goffin’s book is sometimes criticized by jazz historians for the Belgian author’s embellishments, but the narrative is believed to have been largely based on notes Armstrong provided to Goffin.)

“He went back to Charlie’s and sold newspapers; but his earnings were very small, and, after all, he could not sell papers for the rest of his life!” Goffin continues. “He tried his hand as odd man in a dairy, doing all the heavy chores; but after a month of this he returned to Charlie’s newsstand.”

This newsstand, Goffin writes in another section, was based at Canal Street and St. Charles Avenue. Thomas Brothers, a professor at Duke University who wrote the book Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans, confirms the location where Armstrong would pick up newspapers to sell in downtown New Orleans.

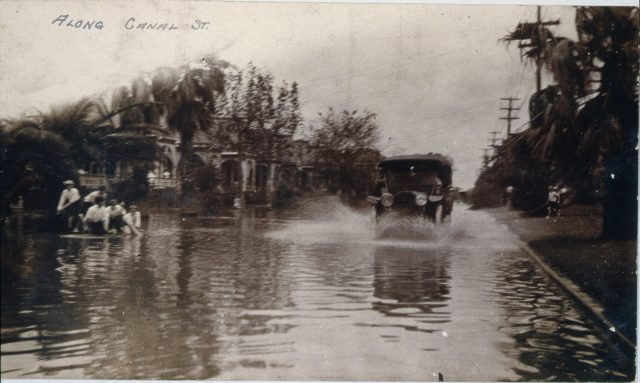

A roughly contemporary shot of Canal Street shows the cars and horse-drawn carriages that shared the streets of New Orleans in the 1910s. Detail. The Historic New Orleans Collection

As it is today, this was a busy part of the city in 1915, and the site of heavy foot traffic.

An eight-second silent film clip shot in that year and posted on the Getty Images website captures a sea of humanity a stone’s throw away, on the other side of the Canal Street neutral ground; the camera is facing down Canal toward the river, probably at Dauphine Street, near the flagship D. H. Holmes store.

White women and men, all of them in hats, stride past one another. Several men in suits stand at the corner, perhaps waiting for someone. A young boy looks toward the street as he holds a woman’s hand. Automobiles and a streetcar are visible in the background.

Just over three seconds into the footage, an adolescent black boy walks into the scene. He is wearing a newsboy cap. The sleeves of his white shirt are rolled up to the elbows.

The boy turns around. He’s selling a newspaper, what appears to be the New Orleans Item.

The boy seems to acknowledge the camera, perhaps the only person in the clip who does so overtly. For a brief moment he flashes a brilliant smile, showing ease as a young black man among white pedestrians during a particularly oppressive period of the Jim Crow era. And then he turns away to continue selling his paper.

That newsboy, according to two prominent jazz historians, appears to be Armstrong himself, at thirteen or fourteen years of age. If it is him, it would be the oldest video footage of the future recording star by well over a decade, and it would depict him at a critical crossroads in his life, after he had left the stability of the Colored Waif’s Home and before he became a full-time working musician. It would also presumably depict him around the time his voice changed from a tenor to his famous baritone, presumably calling out the headlines as he hawked the paper.

The timing is right. The age and complexion of the newsboy are right. The location is right. And the newsboy, by some accounts, has something intangible in his brief interaction with the camera, a striking charisma.

Confirming with certainty that the newsboy is Armstrong is not an easy thing to do more than a century later, of course. There are no known records on the brief film. Even if people involved in the production of it could be identified today, the chances that they are still alive would be very slim. No one who knew Armstrong when he was a child is known to still be alive. Armstrong himself has been dead for nearly a half-century.

But there are people who knew Armstrong later in his life. Among them is Dan Morgenstern, the former editor of DownBeat magazine and former director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University. Morgenstern, who was friends with Armstrong from 1950 until the jazz icon’s death in 1971, believes the newsboy in the film clip is the artist as a young man. “There is a special aura Louis had, and it’s there to me, for whatever that’s worth,” Morgenstern said in an email after viewing the clip.

A comparison of a screen grab from the 1915 film clip with a photograph of Armstrong from around 1920 shows that the distance from eyes to nose and nose to mouth is the same, as well as the width of the nose. It matches up perfectly. Such an exercise can be helpful in identifying a person, said Kurt Luther, a professor of computer science at Virginia Tech University who is leading a project called Civil War Photo Sleuth that attempts to identify people in Civil War–era photographs. But it’s not necessarily conclusive.

“If the facial features match up, it’s only a start,” Luther said in an email. “We need to consider the surrounding context (environment, clothing, etc.), what we know about the photos, the dates and locations, how distinctive the face is.” Ultimately, Luther said, “you would want to seek out the consensus of jazz historians.”

Morgenstern thinks it is Armstrong in the film clip, as does Ricky Riccardi, archivist at the Louis Armstrong House Museum in New York and author of What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years. Others are less certain. But there is a broad consensus among a group of Armstrong experts that, based on the circumstances and timing, it could be him.

Tin Lizzies in formation line the streetcar tracks on Canal Street ca. 1923. The Historic New Orleans Collection

“I think it’s entirely possible that the boy carrying the newspaper is Armstrong,” wrote Terry Teachout, author of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, in an email. “He certainly bears a very strong facial resemblance to the child seen in the familiar photo of Armstrong and the Waif’s Home band. I wouldn’t want to go any farther than that—it’s far too easy to be swayed by wishful thinking—but I can’t see any reason to rule it out.”

Michael White, a jazz historian and professor at Xavier University of Louisiana, said in an email that he is “cautious to say that this is Armstrong.”

“At times it looks like him, but at times it doesn’t,” he wrote.

Riccardi, of the Louis Armstrong House Museum, described the film clip as “an unthinkable find” and said that the comparison of the screen grab to a known early photograph of Armstrong “was what did it for me.”

“I never could have dreamed that footage would turn up of young Louis Armstrong hawking newspapers, just before turning towards music as his full-time occupation and soon after that changing the sound of American music. We might never know for sure if the kid in the video is really him, but when he turns to the camera—fully aware of its placement—and flashes that smile, the film lights up in a way that sure reminds me of Armstrong.”

It is indeed difficult to fathom that a teenager who would become the king of jazz would randomly walk into a street scene in a silent film clip recorded before the word “jazz” was even in the American lexicon. New Orleans was a city of more than three hundred thousand people in 1915. What are the chances?

Armstrong was not listed as a newsboy in either census; he was only nine years old in 1910, and by 1920 he was already a professional musician. But the census figures suggest that there were few black newsboys in 1915. Armstrong was one of them.

The New Orleans census for 1910 listed forty-eight residents of the city who identified their occupation as newsboy, according to John Kelly, a reference librarian at Southeastern Louisiana University. Of those, four were identified as black and one as mulatto. The 1920 New Orleans census identified forty-four people who listed newsboy as their occupation. Five were identified as black and four as mulatto.

But there are some discrepancies in the numbers. The official 1910 federal census counted 233 newsboys of all races in New Orleans, and the 1920 report counted 107 (and one newsgirl). Kelly said the differences result from the fact that the census definition of “newsboys” included others involved in newspaper delivery, such as those who identified themselves as “carriers” or “agents.” Newsboys typically walked around and sold single copies of papers to pedestrians, as the boy in the silent film clip appears to be doing.

Armstrong was not listed as a newsboy in either census; he was only nine years old in 1910, and by 1920 he was already a professional musician. But the census figures suggest that there were few black newsboys in 1915. Armstrong was one of them.

The source of the film clip, Getty Images, has little information about it, other than that it was shot in New Orleans in 1915. It is labeled on the website as “B/W people walking on crowded sidewalk / New Orleans / 1915 / NO SOUND.” According to a Getty customer service representative, the video has been on the company’s website since 2007. The presence of the newsboy who strongly resembles Armstrong appears to have been first noted by this writer during a search for other silent film footage of Armstrong that may exist.

A banner headline, “Bandits Wreck N.O. Train,” appears below the newspaper’s name and above a photograph on the front page, but pinpointing the date has proven difficult. The afternoon Item was the only major paper in New Orleans to use this design regularly at the time. The States, another afternoon daily that later merged with the Item, typically ran headlines above the nameplate. The morning Times-Picayune did not run headlines across the entire width of the front page in this era. The French-language l’Abeille did not typically run photos on its front page.

There were numerous bandit/train wreck incidents in 1915, but a search of several digitized and traditional microfilm newspaper archives does not turn up any edition of the Item with that headline. There are several possible explanations for this. One is that the paper printed more than one edition most days. The paper being sold by the newsboy may be an early edition; final editions, which contained different content, were most often preserved on microfilm. Another possible explanation is that there are gaps in the issues of the Item from 1915 that are preserved in archives. A period of about a week and a half from January and February of 1915 is missing, for instance, from the digitized and microfilm collections of the New Orleans City Archives and the microfilm available from the Historic New Orleans Collection. The Louisiana State Museum has in its collection bound editions of the Item, but the entire year of 1915 is missing. It is possible that the “Bandits Wreck N.O. Train” headline appeared on one of the missing days.

There is no evidence of storm damage in the video footage, nor in several other New Orleans silent film clips listed as being in the same series as the one in which the newsboy engages with the camera. A powerful hurricane came ashore September 29, 1915, near Grand Isle, killing more than two hundred people and leaving millions of dollars in damage in its wake. The local papers covered the storm and its aftermath for weeks, often on the front page. It is reasonable, therefore, to consider it likely that the film footage was shot prior to that catastrophe.

Armstrong’s period of occupational uncertainty after serving his sentence at the Waif’s Home is described in a 1931 story published in the Item. “When he was discharged as a reputable youngster a year and a half later,” the Item reports in the story published during what was believed to have been Armstrong’s first trip back to his hometown after he became a recording star, “it never occurred to him to stick to music. Instead, seeking to support himself, he became a newsboy, selling Items in a lusty voice at the corner of Poydras and Baronne streets,” six blocks away from the scene shown in the 1915 silent film clip.

It is indeed difficult to fathom that a teenager who would become the king of jazz would randomly walk into a street scene in a silent film clip recorded before the word “jazz” was even in the American lexicon.

And his hustle as a newsboy overlapped with his early performances as a professional musician, Armstrong writes in his 1952 autobiography, Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. He says that when his cousin’s son Clarence (whom he later adopted) was born in August of 1915, he was doing a little bit of both jobs as he tried to eke out a living.

“My whole family had always been poor, and when Clarence was born I was the only one making a pretty decent salary,” Armstrong writes. “That was no fortune, but I was doing lots better than the rest of us. I was selling papers and playing a little music on the side.”

Armstrong gigged in the honky-tonks of his neighborhood, and he played parades and funerals as he polished his chops and built his reputation. By the time he registered for the World War I draft on September 12, 1918, shortly after he turned seventeen years old (Armstrong is believed to have given the wrong birthdate when registering for the draft, making it appear as though he was eighteen), he no longer considered himself a newsboy or a laborer. “Musician” was written under “present occupation.”

James Karst is a jazz history researcher and writer best known for discovering that Louis Armstrong had been arrested at the age of nine on a “dangerous and suspicious” charge in downtown New Orleans.

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos