Labor Day weekend is a time to honor our workers, and the spirit of industry they embody.

When thinking about a Labor Day edition of Take Five, I decided to bypass the standard fare — like Cannonball Adderley’s “Work Song,” which refers to a different set of circumstances than the one that this holiday commemorates. I looked instead to important jazz artists who were born this week in history, within several days of the holiday.

This is just scratching the surface: a more comprehensive list would include David Liebman, Peter Bernstein and Makanda Ken McIntyre, among others. But it stands as a good, swinging nod to both the meaning of the holiday and a glorious set of birthdays that happen to fall this week.

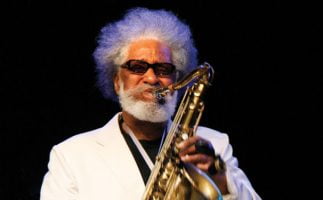

Sonny Rollins, “There’s No Business Like Show Business”

Sonny Rollins, the Saxophone Colossus, turns 88 this Friday. His life and career have been a model of discipline and hard work; consider the now-famous story of his self-improvement sabbatical on the Williamsburg Bridge, which has led to a campaign to rename it in his honor. About five years before he took to the bridge, Rollins made Work Time, an album for Prestige featuring Ray Bryant on piano, George Morrow on bass and Max Roach on drums.

The opening track is a breathless dash through Irving Berlin’s “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” Along with highlighting the matchless hookup of Rollins and Roach, it serves as a reminder that show business is indeed a business, and on some level its practitioners are just doing their job.

Clifford Jordan and John Gilmore, “Status Quo”

Clifford Jordan is another great tenor saxophonist born around Labor Day. He hailed from Chicago; in fact, his debut for Blue Note was Blowing in From Chicago, featuring another hometown tenor hero, John Gilmore. Recorded in 1957, the album has the sterling rhythm team of bassist Curley Russell and drummer Art Blakey; on piano is Horace Silver, who shared the same birthday as Jordan, Sept. 2.

The opening track is a boppish workout by John Neely called “Status Quo,” a contrafact of the standard “There Will Never Be Another You.” The back-and-forth between the tenors is as hearty and satisfying as the fusillades in Blakey’s drum solo. And let’s not forget that “Status Quo” is something that the American labor movement, which originated in Chicago, set out to disrupt.

Gerald Wilson Orchestra, “Detroit”

Speaking of American cities with a strong history of organized labor, I spent the holiday weekend in Detroit, for that city’s long-running jazz festival. Not quite a decade ago, for a 30th-anniversary celebration, the festival commissioned a piece from one of the Motor City’s emeritus jazz heroes, composer-bandleader Gerald Wilson. He rose to the occasion with “The Detroit Suite,” a six-part invention inspired by his formative upbringing. (One movement bears the title “Cass Tech,” after the alma mater that claims him along with so many other jazz legends.)

This piece, simply titled “Detroit,” is the third movement in the suite — an elegant, drifting ballad that feels like a tip of the baseball cap to Wilson’s contemporary Thad Jones. As recorded for an album by the same name on Mack Avenue, the piece features a suavely imploring solo by a young tenor saxophonist named Kamasi Washington. It’s a good reminder of how much work Wilson was able to put in well past the standard retirement age. His centenary falls this Tuesday, Sept. 4, and this is just one of many tracks to remember him by.

Joe Newman, “Jive at Five”

Trumpeter Joe Newman was born in New Orleans on Sept. 7, 1922. He led a workmanlike career, in the best and truest sense of the word. A seasoned sideman who got his start with Lionel Hampton, he was still in his early 20s when began his historic association with Count Basie. Years later, in 1960, Newman convened a pair of fellow Basie alums — tenor saxophonist Frank Wess and bassist Eddie Jones — for Jive at Five.

The title track, a piece by Basie and Harry “Sweets” Edison, sits in a comfortable mid-tempo, swinging easy. (Tommy Flanagan is the pianist, and Oliver Jackson is the drummer.) Listen for the transition from Wess’s tenor solo to Newman’s own. And consider the unspoken implication of the title, which nods toward quittin’ time.

Horace Silver, “Summer in Central Park”

As noted above, Horace Silver was born on Sept. 2 — on 1928, in fact, 90 years ago. He was another jazz musician who embraced the redeeming qualities of honest work. At the same time, he was someone who knew how to have fun. So it feels apt to close this week’s Take Five with a track that acknowledges Labor Day weekend as a time for recreation and enjoyment of the waning days of summer.

This is “Summer in Central Park,” from Silver’s underrated 1973 Blue Note album In Search of the 27th Man. It features a fraternal front line of Randy and Michael Brecker, along with David Friedman on vibraphone, Bob Cranshaw on electric bass and Mickey Roker on drums. The song is a tuneful waltz, its stated locale and melodic shape that suggesting a response to John Lewis’s “Skating in Central Park.” (The vibes reinforce that connection.) Notably, it’s set in a sunny major key and an unhurried but lively tempo; you can easily imagine it as a soundtrack for a meandering afternoon on the Great Lawn.

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos