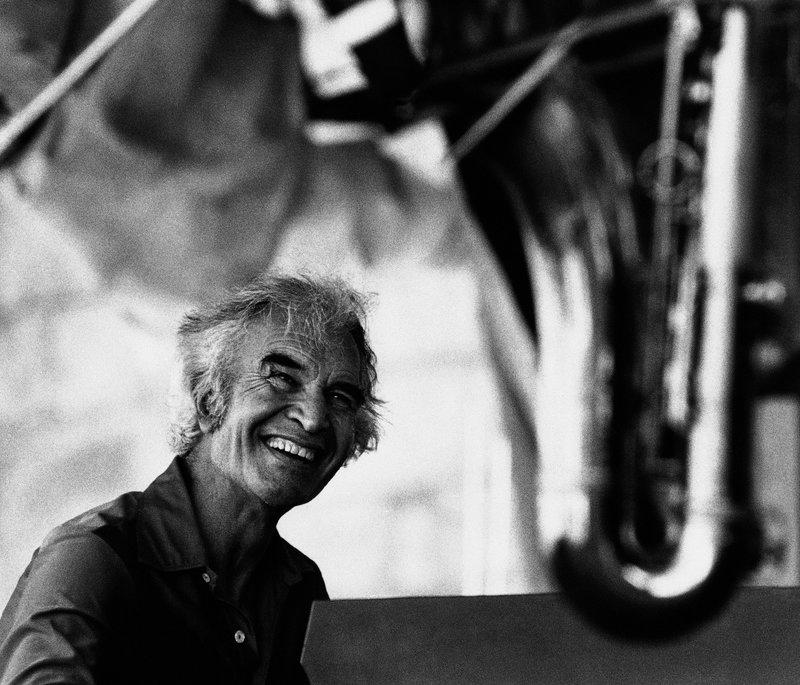

For some 60 years, beginning in the early 1950s, pianist-composer Dave Brubeck was one of the most famous jazz musicians alive.

During the height of that fame, he was as popular in the general public as icons like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington — two of the only other jazz artists ever to appear on the cover of Time magazine. Brubeck played the same festivals as Pops and Duke, sharing equal billing. And he’s the rare jazz musician to have scored a true hit song: “Take Five,” composed by alto saxophonist Paul Desmond but released by the Dave Brubeck Quartet.

Brubeck’s compositions are still in circulation; jazz musicians in particular like “The Duke” and “In Your Own Sweet Way.” And he was equally popular as a pianist. It’s no wonder that a new biography by Philip Clark, Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time received considerable press in advance of its publication this week.

But among jazz musicians, jazz critics, and “hardcore” jazz fans, Brubeck’s piano playing has largely been either vilified or ignored. If a pianist says his or her main influence is Brubeck, that will almost guarantee a negative reaction in those circles.

In fact, there are very few pianists today who openly credit Brubeck as an influence. One of the few is Ethan Iverson, who told me that “Brubeck is one of my biggest primary influences.” (Ethan also notes that in an interview with Keith Jarrett posted on his blog, Do The Math, Jarrett recalls some formative experience with a solo piano album, Brubeck Plays Brubeck.)

Again, there’s always an exception. But when I searched digitally through the 3,300-plus entries in the Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz (compiled by Leonard Feather and Ira Gitler), where many musicians specifically list their favorites, I found none who cited Brubeck.

So for this Deep Dive, it is Brubeck’s piano playing that I’ll focus on, before making some general points about his legacy. I’d like to examine his music to try and understand this extreme disconnect between musicians and the broader public.

First, let’s consider a few examples to show that this disconnect is very real:

Brubeck was omitted from the Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz — both the original 1973 LP edition and the 1986 LP and later CD editions. For many years, teachers worldwide used this collection as the basis of their jazz history courses, which means that Brubeck wasn’t played in class unless the teacher brought in supplemental recordings. That collection was replaced by Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology in 2011, which does contain Brubeck’s “Blue Rondo á la Turk.” But a CD collection no longer has the same kind of impact in our era of streaming. (John Hasse, now retired after many years at the Smithsonian, tells me that Brubeck was deeply hurt at being omitted from the classic set, and was delighted at being included in the new one.)

Brubeck was also omitted from Jazz Piano: A Smithsonian Collection, even though it includes recordings by a number of pianists who, while excellent and deserving, don’t have nearly the name recognition as Brubeck, such as Jimmy Jones, Ellis Larkins, Dave McKenna and Ray Bryant.

I found several books of jazz history, or surveys of “great jazz artists,” that make absolutely no mention of Brubeck. More often, he’s mentioned in a page or less, sometimes condescendingly. For example, Jazz, a major textbook by Scott DeVeaux and Gary Giddins, says:

The Brubeck Quartet blew both hot and cool, in the contrast between Desmond’s ethereal saxophone and Brubeck’s heavy-handed piano. …Brubeck[’s] solos …climaxed with repetitive blocks of chords, generating either excitement or tedium, depending on the listener’s taste.

Clearly this is DeVeaux and Giddins telling us that they don’t like Brubeck’s solos. I teach historiography — the study of how history is written — and I would argue that to denigrate or omit one of the most popular jazz artists of all time, simply because you don’t like his work, is not history. It’s as strange as omitting Bach from a history of classical music because you don’t like Bach’s music. History is not about your personal ratings. History is not record reviews. (Full disclosure: Thirty years ago, I coauthored a jazz history book which makes some of these same errors. I hope that I know better now.)

If Dave was as famous as Louis, Duke and Miles Davis, why do they each get a full chapter in every jazz history text, while he gets no more than a page? And if he got a chapter, it needn’t be simplified. A discussion of the controversy around Brubeck would be relevant and appropriate to the writing of history.

The most common opinion that I’ve heard and read all my life holds that Brubeck is an excellent composer, but his piano playing is heavy-handed and doesn’t swing. That it’s Paul Desmond who “makes” the quartet. There’s a good chance you’ve held this opinion yourself.

Let’s pause here to consider a musical example. I’ve chosen one complete long solo, from a Parisian television broadcast, in November 1967. (This is not the set that was released as The Last Time We Saw Paris; it’s unreleased footage, which we’re posting here with permission from the Brubeck estate.)

What you see and hear in the clip is Brubeck’s solo on a standard, “These Foolish Things,” in the usual key of Eb. Try to follow the chain of events, without reading any further. [PAUSE reading while you listen!] After taking in the clip, see if this rundown describes your experience:

· Dave begins by playing lyrical chords.

· Next there’s a repeated top note, with interesting chords under it — substitutions that retain the general motion of the original chords but are not the exact chords.

· He starts playing parallel chords in a different rhythm (not exactly double time) over the static rhythm section.

· Second chorus: he continues this, now closer to actual double time.

· He quiets down and presents a new melody, not “These Foolish Things.”

· Then he slows down, playing a different rhythm over bass and drums. He comes across a snippet of “Somebody Loves Me” (he smiles here) and decides to pursue that idea, playing in a nice stride/swing style. (Take note of how comfortable he is in this style.)

· He hands the baton over for a bass solo.

In many ways, this solo doesn’t fit the practice of modern jazz piano. It’s primarily chordal, not oriented around linear melodies. And there’s no clear delineation of choruses, or even of the chord changes! In short, this is nothing like the approach of, say, Tommy Flanagan, as Dave’s critics frequently complained. But if he had been another Tommy Flanagan, his contribution to jazz history as a pianist would have been precisely zero.

To try and explain this, critics love to say that Brubeck was a classical pianist who learned to improvise. That is absolutely false. He was not seriously involved in classical music, except for the kind that everyone gets in piano lessons, such as he had with his mother. It’s clear from everything Dave ever said about artists like Art Tatum, Fats Waller and Cleo Brown that his focus was playing popular songs and swing piano.

And remember that, this being his centennial, Brubeck was born in 1920. By the age of 22 or so, his swing style was well established. Consider this 1942 performance of “I’ve Found a New Baby,” in which he sounds very much like Tatum or Teddy Wilson.

Now, where does classical music come in? Dave’s older brother Howard was already studying with Darius Milhaud, a French modernist composer who was Jewish and fled to America. Dave began studying with Milhaud after his service in World War II. So began his personal journey into… not classical music overall, but specifically the concepts of Milhaud. It’s clear from his own classical pieces that Brubeck was never all that well versed in, for example, Stravinsky, Bartok, Xenakis, Stockhausen, or other canonical 20th century composers.

The Milhaud influence on Brubeck as a composer is clear. Dave’s early octet pieces are obviously in a Milhaud style. These are fully written pieces with no improvisation; examples include the “Serenade Suite” and “Playland-At-The-Beach,” written and recorded between 1946 and 1948. (Dave did not preserve the exact dates of the earliest octet recordings.)

However, I believe his piano improvisations are also heavily influenced by Milhaud’s teachings — teachings that might be documented in Milhaud’s notes and/or Dave’s notes, which are not currently available. This aspect has not been adequately explored, and would be a worthy research project for someone who wants to spend time in the Brubeck family archives, which recently relocated to Wilton, Conn.)

In short, Brubeck was a swing player who overlaid classical music and modern jazz onto his swing style, not a classical player who got into jazz. The critics got it exactly wrong. And because his style was well established by 1942, his swing feel was an older approach, not fully compatible with the modern bebop feel — and, one could argue, not fully compatible with his rhythm sections, which were in the modern vein (even though they were not at all in the modern vanguard).

This partly explains why people said Brubeck didn’t swing. There was yet another disconnect, between his time feel and his rhythm sections. He probably would have sounded more swinging with a Fats Waller-type of rhythm section.

But there’s more to this question of swing. It’s all too easy to misunderstand Brubeck’s infamous comment that “Any jackass can swing.” He followed this by trying to explain that swing is not everything; it’s more important to try and innovate. What I think he was trying to say is: What would swing have to do with the solo you just heard? Should he have omitted all the rhythmic complexity in order to make it swing more? What would be left?

The so-called Jazz Police love to say that jazz is about freedom, but what they really mean is that it’s about freedom if you do it the way that they consider “correct”! In fact, I’ve worked with both straight-ahead and so-called free jazz musicians, and I’ve noticed that even “free” players have very fixed ideas about the “right way” to play free.

For example, the late Cecil Taylor, whose work famously broke away from any traditional concept of swing, wrote in 1952 — in an unpublished letter to his friend and fellow New England Conservatory student, composer Robert Ceely — that he liked Brubeck’s music, but: “If only he could swing more when submerging himself with those wonderful sounds.” (This comes courtesy of Christopher Meeder, my friend and former grad student, who will soon publish some of his excellent research on Taylor.)

Brubeck’s technique of improvisation was quite free. In fact, it was sometimes avant-garde and totally outrageous.

Consider this solo on “This Can’t be Love,” from 1952. As it unfolds, it becomes fierce and loud, crunchingly dissonant, and stands as a self-contained moment that does not depend on its rather distant connection with the source material.

I hope I’ve helped explain why the jazz establishment had so much trouble with Brubeck’s pianism. But then why was it such a hit with the broader public? For one thing, a general audience doesn’t come with all these preconceived notions. It’s my impression — and there’s still time to document this before it’s too late, if someone wants to do the research — that his devoted audience included a much larger percentage of people who were new to jazz, compared especially with the fanbase of someone like Miles Davis. In fact, Brubeck makes this point in the Time cover story, when he says that many of his fan letters specifically state that his was the first jazz they liked.

Then there is Brubeck’s truly spontaneous improvisational method, which appeared to go something like this:

· Start with an idea — any idea — and build from there, regardless where it takes you.

· Keep the general motion and key centers of the chord progression, but not the exact chords.

· It’s OK to change it from major to minor in the same key (he often does this).

· Forget completely about being beholden to any tradition: play “free” over the chord “changes,” regardless of the bass and drums (who continue to play the changes and the straight time feel, to play over).

Brubeck found a lot of freshness using this approach. When you compare takes from his recording sessions, there’s rarely much similarity between two solos on the same tune. That’s something we are all supposedly striving for as jazz players. And his method of keeping the general sense of the chord progression, but not the exact chords, is what many jazz masters do in practice. It’s how one breaks free from the tyranny of the chord sequences.

For many novice listeners, this approach to improvisation seems to involve them in the process in a way that doesn’t happen with more conventional jazz solos. They don’t need to “follow the form” or the choruses; they just follow his process of discovery as he moves from one idea to the next. And Dave played with intense focus and a high level of energy, qualities that are readily apparent onstage or onscreen.

Now that you’ve followed my line of reasoning, it should make sense that there are so few pianists who profess to be disciples of Brubeck. His approach is not a “style.” It wouldn’t make much sense to transcribe him, or to learn his solos and licks. Because the whole point is to hit one note or chord and see where it leads you. It’s the process, not the notes — a process that everyone can learn from, without sounding anything like Brubeck.

Does this method work all the time? Of course not; it’s a high-risk approach. Using a standard approach to jazz improvisation would be a surer way to a high batting average. (Even a relatively uninspired Flanagan solo still sounds excellent, whereas an uninspired Brubeck solo can indeed sound “heavy-handed,” as is often claimed.)

While we’re here, let me briefly address a few more issues regarding Brubeck’s legacy. I’ve seen a number of articles from the early ‘50s that label his music “cool,” and the lead sentence in his Wikipedia entry says that Brubeck is “considered one of the foremost exponents of cool jazz.” Well, this could be a whole other essay, so suffice it so say for now that somehow the label “cool” was and is used to mean “good,” and has nothing to do with the actual sound of the music. Clearly there is nothing “cool” — in the usual sense of quiet and emotionally reserved — about the audio samples connected with this essay. Interestingly, the breakthrough cover story in the Nov. 8, 1954 issue of Time leaves the issue open, saying that “Spokesmen for various jazz cliques have claimed that it … is cool (or hot).”

Speaking of that Time story, let’s clear up a few things: There has been much discussion, including by Brubeck himself, about how this white artist wasn’t deserving of such a tribute. But Dave was not the first jazz musician to be featured on the cover of Time. That honor had gone, appropriately, to Louis Armstrong in 1949.

And after Dave became the second one, Time featured Duke (in a story that was, by the way, already planned before his 1956 Newport Jazz Festival appearance), followed by Monk (in 1964), and Wynton Marsalis (in 1990, as part of a larger article on the state of jazz). Time clearly did not “favor” white jazz artists. The bigger surprise was that Brubeck was a brand-new star. By 1949, Armstrong had enjoyed 20 years of fame. Ellington by ‘56 had innovated for about 30 years since appearing at the Kentucky Club in midtown Manhattan. If, say, Benny Goodman had appeared on the cover, probably nobody would have blinked an eye. But who was this new upstart Brubeck, to be on the cover of Time? On top of that, as we’ve seen, his piano playing was controversial, nowhere near being accepted among the musicians and critics as one of the greats.

In any case, Brubeck was famously outspoken against racism. In early 1960, he turned down a lucrative offer to tour colleges in the South because they required that he replace his black bassist, Eugene Wright, with a white person. And Brubeck’s musical The Real Ambassadors had Armstrong, Carmen McRae and others singing lyrics by his wife, Iola, that pointedly tackled racism and imperialism. (Keith Hatscheck of the University of the Pacific is working on a book about this fascinating musical, which was recorded and released but never staged.)

Of course, Brubeck’s most recognized contribution is the use of meters other than 4/4 and 3/4. I don’t like the expression “odd meters,” which sounds a bit derogatory, but I am OK with “longer meters,” as in “meters longer than 4.” The iconic album Time Out was recorded over three dates in the summer of 1959 and released that December. (Stephen Crist’s 2019 book about this album, for which I provided a blurb, has a tremendous amount of new biographical research and musical information.)

It has been noted that Max Roach released the album Jazz in 3/4 Time in 1957, and that he was apparently performing “As Long As You’re Living,” an original tune in 5/4, before he first recorded it in late ‘59. (Here is a live version from 1960.)

But Brubeck was the only one at the time who made “longer meters” a specialty, and who had many such tunes in his repertory. What’s more, even when playing in 3/4, he commonly superimposed a two-beat stride during his solo, a sophisticated technique that Ron Carter and Tony Williams later used on “Footprints” with Miles Davis.

Brubeck’s “longer meters” were not immediately adopted in jazz circles. There was the late trumpeter Don Ellis, who made a specialty of long meters, for example in his 5/4 pieces “Indian Lady” and “5/4 Getaway.”

But the strongest influence of the Time Out album seems to have been felt initially in pop and rock circles. There was the stunning long meter virtuosity of the Mahavishnu Orchestra, among others. The Beatles song “All You Need Is Love” has phrases in 7. “Do What You Like” from Blind Faith was in 5. “Everything’s Alright,” from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar (1971), is in 5/4. The main theme for the Mission: Impossible TV series is an iconic 5/4 piece by Lalo Schifrin.

Long meters became a trademark of progressive rock bands such as Yes, Soft Machine, Pink Floyd, Genesis, Gentle Giant and King Crimson. Frank Zappa often worked in meters other than 3 and 4. Keith Emerson of Emerson, Lake & Palmer wrote a 5/4 piece in 1968 entitled “Azrael, the Angel of Death,” and on his website he cites Brubeck as one of his heroes.

But outside of the occasional 5/4 piece, the wider influence of Brubeck’s longer-meter pieces on jazz appears to have gestated for a long time. It’s only since the mid-‘90s, largely through the influence of artists including Brad Mehldau and Steve Coleman, that longer meters have become so standard that jazz musicians are now expected to be able to play in virtually any time signature. You can now write a piece in, say, 11/8, and bring it to a rehearsal, expecting that musicians should be able to play it (without a lot of groaning). Although there are other factors at play, this feels like part of the Brubeck legacy, possibly filtered through rock, bearing fruit in jazz after so many years.

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos