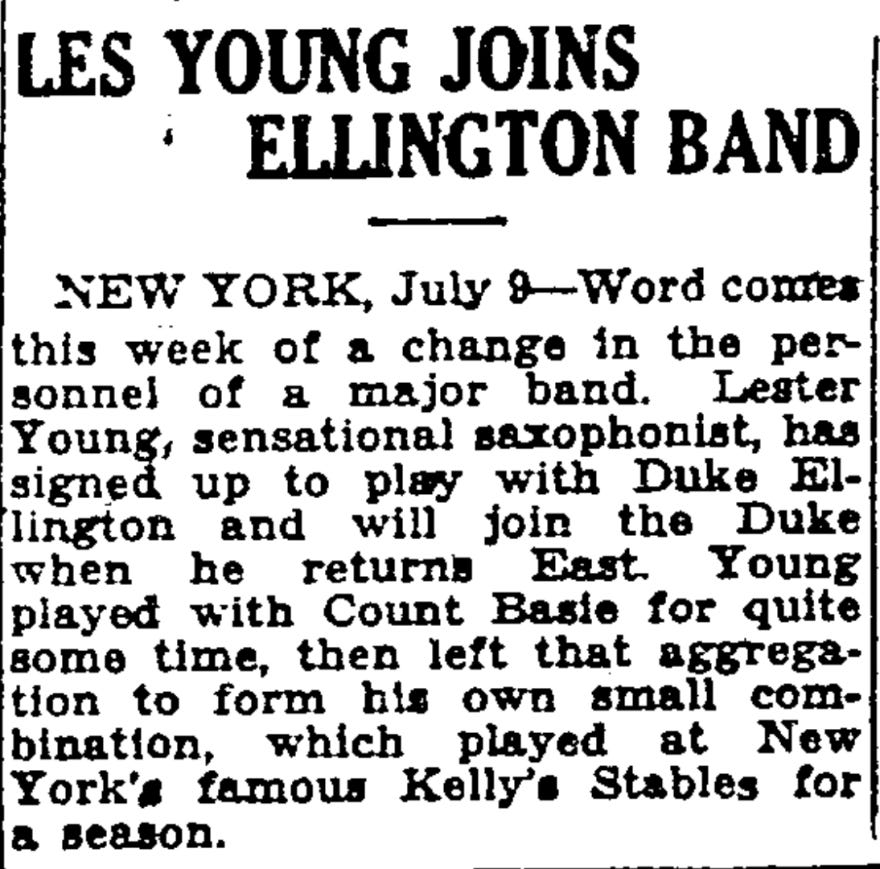

Let me share a press announcement that was not known to Ellington experts I’ve consulted. It states that Lester Young was slated to join Duke’s band in 1942! This never happened, of course; after Barney Bigard left Duke in early July 1942, he was replaced by one Chauncey Haughton.

Don’t forget that Bigard played tenor sax as well as clarinet in the band, and tenorist Pres also played clarinet—so the replacement plan is not as strange as it might seem at first.

Young had left Basie in December 1940. The gig at Kelly’s Stable that is mentioned in the news piece had taken place in February and March 1941. (Musician Bert Kelly called his Chicago club Kelly’s Stables, but his Manhattan club was called Kelly’s Stable, causing plenty of confusion.) That was one of the only times Young had worked as a leader to this point in his career, which is probably why they singled it out. Since then, Lester had mostly worked as the featured sideman to his drummer brother in Lee and Lester Young’s Band, in Los Angeles and Hollywood.

What’s most interesting is that the article — in the Pittsburgh Courier (a distinguished black newspaper)— dated July 9 and published July 11, 1942 — reports that Pres had “signed up” to join the band, not that it was merely a possibility. And notice, the press release doesn’t suggest that this would have been a one-time guest appearance, but that Young would have been a regular member of Duke’s band.

As documented in the amazing Ellington research site TDWAW.Ellingtonweb.ca, the band spent much of the year 1942 in Los Angeles, and they were in town the entire summer, largely to rehearse and then perform Duke’s political musical Jump for Joy, which opened July 10 and closed September 27. Young’s L.A. stint with his brother Lee’s band was to end in late August, so it makes sense that he and Duke would have spoken in early July, when Bigard left, about what happened next. Pres did indeed come back East, but instead of joining Duke, he went with the original plan, which was to remain in Lee’s band when they performed at Café Society in downtown Manhattan starting September 1, 1942.

Pres was so closely associated with Basie — as closely as, say, Johnny Hodges was with Duke— that it’s astounding to think that such conversations were going on. This unknown little news item boosts our knowledge of how widely Lester Young’s genius was appreciated. Before Basie, Fletcher Henderson had reached out and hired him in 1934 (it famously didn’t work out for more than a few months — but still, it happened). Then came Basie. It isn’t widely known, but Benny Goodman indicated that Young was his favorite saxophonist, and that Basie’s was his favorite band; it’s no accident that they were both guests at Goodman’s famous Carnegie Hall concert in January 1938. In October 1940, during a lull in Basie’s touring activity (long story, but Basie had management issues, which may have even had something to do with Pres leaving two months later), Goodman reached out with an offer (and a recording session, not issued until 1972) to actually hire Pres, Basie, and other Basie band members for his own group! And now we can say for certain that Pres was also admired by Duke.

Why didn’t it happen? If I had to guess, I’d speculate that Duke somehow hadn’t realized that Pres’s unique, spare and ethereal clarinet style was such a far cry from Bigard’s flashy, virtuosic approach that he couldn’t possibly fill Bigard’s role on that instrument. A different role, yes, but not like Bigard, and I’m guessing that another Bigard is what Duke wanted. But nobody thought to ask about this event while any of the involved parties—the musicians and the management—were alive. So we’ll never know for sure.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SWh2x8RUbY

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos