The real advantage Born to Be Blue has over Miles Ahead is that it uses the music as a way to get into its title character’s soul.

As a lifelong fan of both Miles Davis and Chet Baker, when I found out that there was going to be not one released this year I couldn’t wait to check them out. It’s the kind of thing I wish more people were excited about; in today’s culture, jazz is pigeonholed by too many as pretentious or incomprehensible music, which is a shame considering how thrilling and life-affirming it is. Telling the stories of the life and times of two of jazz’s greatest artists ought to help make jazz a bigger cultural phenomenon than it is. Ray Charles and Johnny Cash earned fresh attention and relevance in the mainstream after their biographies met with commercial and critical success — why not do the same for jazz?

There’s no doubt that Miles Ahead was a labor of love. Don Cheadle shows admirable commitment in producing, directing, co-writing the screenplay as well as starring in the film. He also did the crowdsourcing to fund the project over many years, and was evidently told by the powers that be that having a white co-star was a “financial imperative.” The fact that Miles Ahead took so long to make, and was held to a creepy racial standard, serves as a depressing indication of how little confidence Hollywood had in a biopic, even of the life of someone as interesting as Miles Davis. Another observation: if it’s going to be compelling for jazz heads and newcomers alike, a biopic must trust in the power of Davis’ music, have faith that it will help illuminate his life. And that is where Miles Ahead falls short.

It’s not like Miles didn’t surround himself with interesting people, either. There’s very little mention in the film of his illustrious history of band mates and sidemen, which include the likes of Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, and Herbie Hancock. It could have been amazing to see these vivid personalities, who helped Miles make some of the greatest music of all time, dramatized on the screen. What good is it to relegate them to occasional side comments or toss them aside as unidentified window dressing? It makes one wonder what a more seasoned director could have done with the film, and whether or not Miles will ever get a better cinematic treatment than this one.

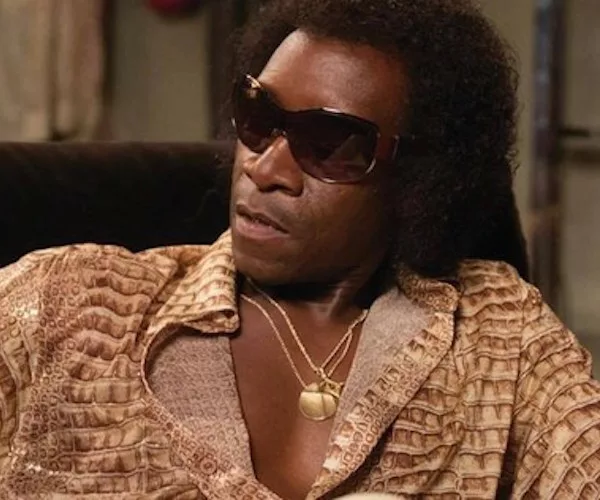

The Miles we meet is from his dissolute 1975-1980 period: the so-called “Prince of Darkness” has gone to seed, holing up in his basement and brooding. As Davis, Cheadle gives an excellent performance, balancing Davis’s icy reserve and flamboyant arrogance with fleeting glimpses of the deep sensitivity that made his playing so seductive. The scowl and the impassive shades are worn like battle armor, his throaty whisper and laconic sarcasm used as weapons. We see Miles as a living legend but one who has started to feel like a relic, which is the least dramatically interesting way to imagine him as a character.

The plot twists in all directions with increasing levels of implausibility. Sleazy record company goons try to snatch away a recording of Miles’ new demos, causing Miles and the ersatz Rolling Stone reporter (goofily played by Ewan McGregor), who has previously awkwardly tried to break into Miles’ apartment, to suddenly take to the streets in a madcap chase to reclaim the lost recordings. Cue guns blazing and tires squealing. Cheadle’s decision to add car chases and gunfights to the story feels contrived, confusing, and pointless. Did he feel the need to spice up the story to get people interested or was it the pressure of the marketplace?

Miles Ahead suggests plenty of dramatic situations, only to leave them unrealized. Davis’s marriage to the long-suffering Frances receives a truncated and vague treatment. If Miles Ahead is aiming at a general audience then the anguished love story should provide crowd-pleasing satisfaction; but we can’t get involved deeply enough in the emotional life of the characters to care. The peaks and valleys of Miles’ story are interesting enough on their own terms — why resort to standard issue melodrama?

Even when they shared the spotlight, Davis was never fond of Chet Baker, so fact that both of their biopics have been released at the same time is an odd and competitive coincidence. In his autobiography, Miles accuses Baker of ripping off his sound and capitalizing on the fact that his whiteness made him an easier crossover success with predominately white jazz audiences. In Baker’s defense, the accusation isn’t fair to trumpeter’s natural skill and inimitable voice, but the fact remains that, at least for jazz musicians of Baker’s era, Davis was the gold standard.

Baker’s crippling self-doubts are at the center of Born to Be Blue, directed by Robert Budreau. Baker’s character is tested and re-tested: he is always searching for respect. Ethan Hawke plays Baker as genuinely talented, but the man’s devotion to playing meets its match in his addiction to heroin. As a character, Baker is alternately charming and helpless. Bruce Weber’s superb 1988 documentary Let’s Get Lost suggests that the true nature of the trumpeter’s inner life remains an open question.. Did the same person who sang such agonizingly romantic ballads just as easily destroy his life and everyone around him while in pursuit of the next fix?

Hawke’s performance as the laconic Baker is almost as strong as Cheadle’s portrayal of Davis. He finds the isolation and the wounded ambition in Baker’s life. His rise to fame and fortune is derailed after he pisses off the wrong dealer, resulting in a shattered embouchure and a mouth filled with blood. Baker has to relearn how to play music again, at the same time taking demeaning jobs pumping gas and playing in a pizza shop. Chet’s almost entirely sustained by his relationship with his black girlfriend Jane, sympathetically played by the lovely Carmen Ejogo.

It’s interesting that it’s a gruffer, one-dimensional version of Miles Davis that Chet meets backstage in New York after being promoted by none other than Charlie Parker himself as “a little white cat from the West Coast who is gonna eat you all up.” Baker tentatively asks Miles for a comment on his performance: the disdainful response is that he sounded candy-sweet and to come back and play after he’s lived a little. It’s a moment Baker never forgets, and one whose emotional repercussions are felt along the entirety of Baker’s long road to ruin.

The somber mood is repetitively established by several long takes of Baker practicing on the roof of the couple’s RV. After seeing Baker’s desolate home in Oklahoma and his rough, disapproving parents, we see how the intrinsic loneliness of coming of age in that empty landscape gave Baker a kind of alien grace. There’s a compelling contrast at work here; Baker’s oh-so-romantic music doesn’t match his gnarled face and world-weary demeanor. He’s a kind of Dorian Gray in reverse: his looks only worsen as his numberless sins come back to haunt him, but as he ages his performances become more hauntingly beautiful, seasoned by the ravages of time. Just when we think he’s about to redeem his bad choices and go straight for good, we see that “The James Dean of Jazz” isn’t going to reform himself any time soon.

It is this mysterious, volatile mix of powerful music and fragile psyche that Born To Be Blue captures much more cinematically than the disappointingly superficial flash of Miles Ahead. The real advantage the former film has over the latter is that it uses the music as a way to get into the soul of its title character, which is precisely what makes Baker and Davis interesting subjects for a movie in the first place.

Don Cheadle as jazz trumpeter Miles Davis in “Miles Ahead.” Photo: Sony Pictures Classics.

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos