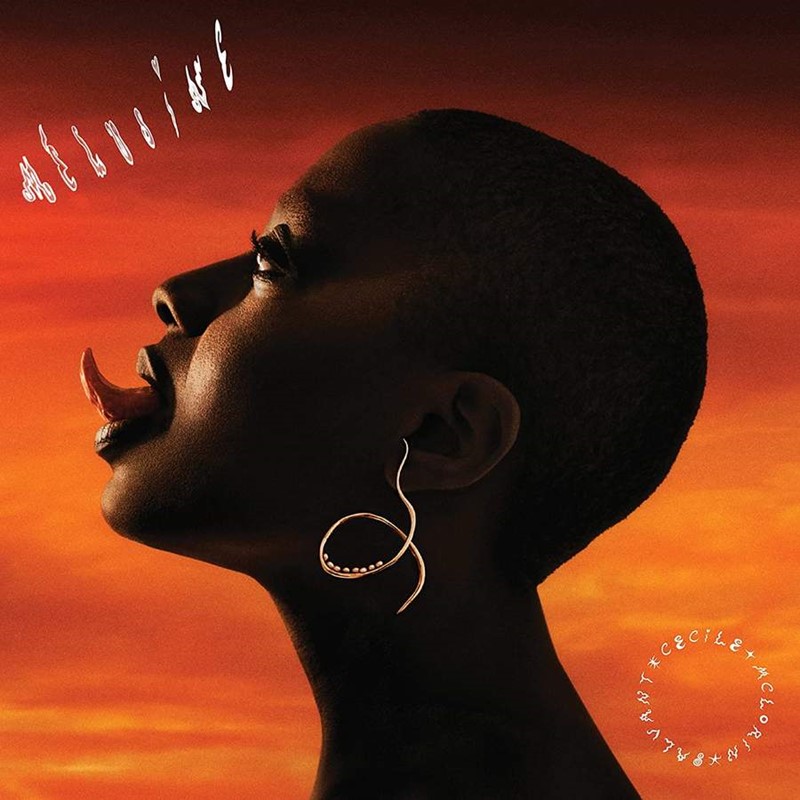

Mélusine, the figure from 14th century French mythology, was a half-woman/half-snake who, when her serpentine self was spied on by her betraying lover, turned into a dragon and took flight.

Cécile McLorin Salvant’s musical vocabulary is a marvel, and not only because she sings in four languages on “Mélusine.” The ambitious concept album mixes original tunes and inventive interpretations of material dating back as far as the 12th century into a potpourri that draws from jazz, Broadway, the Caribbean and more. It’s true roots music. Mélusine, Cécile McLorin Salvant’s new album (released on March 24th), is half-French chanson/half-idiosyncratic art song that, when taken as a whole, reveals itself to be a creature of soaring majesty as well.

Jazz fans may have seen Cecilé McLorin Salvant lounging at the bar at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola, staring out at the car lights buzzing around Columbus Circle, or at a gig with Aaron Diehl where she performs a Big Bill Broonzy tune, or at the Newport Jazz Festival with her contemporary jazz ensemble, or for a performance of her own 2020 opera, the fairytale-like story of Ogresse.

With 2022’s Ghost Song, Salvant revealed herself as far more than “merely” her generation’s most imaginative and thrilling jazz interpreter (with three Grammys and a MacArthur Fellowship to show for it). That album — inventive originals framed by a handful of covers, including a haunted version of Kate Bush’s “Wuthering Heights” and a take on the chirpy Wizard of Oz selection “Optimistic Voices” — stands as a distinctly original work that adheres to no genre. And with her staged cantata Ogresseshe has fashioned her own mythic exploration through senses of self with equal measures of artistic grace and power.

At the age of 33, Salvant has already begun to define her legacy. She has an innate understanding of jazz that allows her to improvise, scat, interpret and mix genres effortlessly. This makes listening to her sing a time loop experience, where you are both in the past and present with the future looming ahead.

The album was inspired by a European fable involving a hunting accident, pivotal bathing scenes and a marriage that goes sour (spoiler alert: The wife turns into a dragon). It’s confusing but fascinating, like a dream about a dream.

Somehow, despite the unwieldy scope of the 45-minute set, Salvant never hits a false note. Whether the words are in French, English, Occitan or Haitian Creole, she sings them beautifully, navigating tricky melodies with the ease of Ella Fitzgerald and a playfulness that enhances Salvant’s astute sense of theatricality. She’s equally convincing singing about the fickle heart, sin and repentance or, say, becoming a dragon.

As Mélusine is a mix, so is the music, often within individual pieces. The drama-laden songs of French 20th century stars Charles Trenet, Mistinguett and Léo Ferré rub elbows with desire-tinged songs of the women troubadours Iseut de Capio and Almucs de Castelnau— torch songs vs. songs originally sung by actual torch-light. Twists on cabaret piano jazz (her frequent collaborators Aaron Diehland Sullivan Fortner both make appearances) get spiked with kalimbaand synthesizers. Ghana-born percussionist Weedie Braimah accompanies Salvant on the African djembeon the 14th century ditty “Dites Moi Que Je Suis Belle” (“Tell Me That I’m Beautiful”). Fortner shifts to a Switched On Bach-ian synth for Michel Lambert’s Baroque-era air de couer“D’un Feu Secret.”

In the course, Salvant celebrates her own heritage — she’s the American-born daughter of French and Haitian parents and grew up with the mix of cultures and languages, though Occitan, the old language of a region of Southern France, she studied on Zoom for this album. One of the medieval pieces is sung in Kreyol, translated from the Occitan by Salvant’s dad, Alix. And in one of four Salvant originals, “Wedo,” our hero Mélusine meets her Haitian counterpart Aida Wedo, a key Vaudou Iwaoften portrayed as, you guessed it, half-woman/half-snake.

That latter song, “Wedo,” closes a brief trio that forms the heart of the album. Both it and the sequence’s opener, “Aida,” feature just Salvant’s layered, wordless vocals and electronic textures. Between them is the title song, with Daniel Swenberg on lute-like classical guitar, as well as the only English vocals on the album.

And that Starmania song? “Petite Musique Terrienne” (“Little Earth Song”), a Salvant favorite from childhood via her mom, about life as an outsider, is used to represent a scene in which Mélusine gives birth to 10 (!) strong but odd sons, because…of course.

Yes, there are a lot of elements put together here. The thing is, this is not about juxtaposition. It’s about synthesis and transformation. Just like Mélusine. Just like Cécile McLorin Salvant.

Salvant’s ability to sing in multiple languages is, in part, due to her being the child of a French mother and Haitian father. She began classical piano studies at 5, sang in a children’s choir at 8, and started classical voice lessons as a teenager. She emerged with a vocal range and talent that one might expect from a performer with significantly more life experience. Yet this old soul, who generally surrounds herself with performers in their 30s, brings a layered depth to her music that comes from historical research and an ability to unearth forgotten songs and make them her own.

The story of Mélusine has a common theme of imagining women as witches, mermaids and other transformative creatures from Greek mythology. It conjures a European folklore legend sung in French, Occitan and Haitian Creole, with her own compositions, and selections dating from the 12th Century. She uses these songs and stories in part to convey a character she often plays in her work – an intelligent coquette who is more interested in playing with men’s affection than seeking it out.

We begin with Mélusine asking “Est-ce Ainsi Que Les Hommes Vivent?” (Is This How Men Live?), bringing in the work of the 20th Century surrealist poet Louis Aragon. Aaron Diehl elegantly uses the piano to make the mood more indigo, more mysterious and to coax the song toward a richer experience.

The story tells of her soon-to-be lover Raymondin, who is wandering in the forest after he accidentally kills his uncle while hunting. He meets and falls in love with Mélusine, as told in the 14th Century song, “Dites Moi Que Je Suis Belle” (Tell Me I’m Beautiful).

Mélusine’s only demand is that Raymondin never visit her on the day she bathes, which of course, over the telling of this tale, he fails to do. They live happily, and he honors her wish until one day, he spies on her in the bath and discovers that on this one day she is part woman, part snake. In the African/Brazilian inspired “Fenestra,” she turns into a dragon and flies out the window.

This often lighthearted album also dips deeply into magic and spirituality. (For instance, “Wedo” references a black serpent creator in Haitian voodoo and the greater African diaspora.) Salvant’s subject matter is informed by her childhood in Miami, growing up in a Haitian/French household, a world where dual language, ethnic traditions and musical influences set her apart from her peers.

More Stories

Interview with Janis Siegel of The Manhattan Transfer: Jazz, being a more refined, interpreted form of music

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos