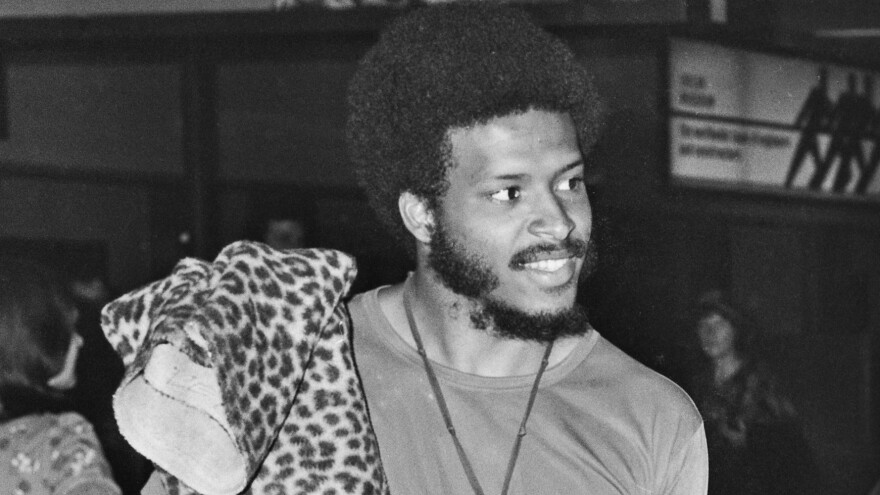

James Mtume, a percussionist who reoriented Miles Davis‘ later rhythms and whose 1983 hit, “Juicy Fruit,” returned to the charts a decade later as the driving force of the Notorious B.I.G.‘s “Juicy,” died on Jan. 9. He was 76. His death was confirmed by his publicist, Angelo Ellerbee.

Mtume recorded with pianist and future NEA Jazz Master McCoy Tyner in 1970, but his big break came the following year, when he started playing congas with Davis’s electric group. Filling the void left by Airto Moreira, Mtume stayed on for four years, appearing on landmark LPs like 1972’s On the Corner and 1974’s Big Fun. “Ife,” from that latter album, had a title near to Mtume’s heart — it was the name of his daughter.

In his 1989 autobiography, Miles, Davis noted Mtume’s impact on the heartbeat of his band: “With Mtume Heath and Pete Cosey joining us, most of the European sensibilities were gone from the band. Now the band settled down into a deep African thing, a deep African-American groove, with a lot of emphasis on drums and rhythm, and not on individual solos.”

In 1978, three years after his departure from Davis, the percussionist traded the rougher edges of “electric Miles” for the smoother zones of funk, and started leading a New York-based group known simply as Mtume. But on its third album, 1983’s Juicy Fruit, the band channeled something deeper. Featuring an icy, snaking bass and a hypnotic line from a Linn drum machine, the flirty, laidback title track etched itself into music history, grabbing the No. 1 spot on the Billboard R&B chart and placing Mtume’s prowess as a solo artist straight into the spotlight.

In 1994, the sounds of “Juicy Fruit” were once again in the air, this time as a sample in the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Juicy.” Boasting perhaps the most famous opening lines in hip-hop — “It was all a dream, I used to read Word Up! magazine / Salt-N-Pepa and Heavy D up in the limousine” — “Juicy” cracked the Top 40 alongside other Biggie hits like “Hypnotize” and “Mo Money Mo Problems.”

“Oh, I dug it,” remembered Mtume about “Juicy.” “They actually wanted me to be in [the music video]. I was asked and I said, ‘No, you ain’t doing that man. What? You want me to jump around the corner in some high shoes and plaid pants?’ They fell out laughing. ‘It’s your generation, you all do what you do.’ ”

James Mtume was born on Jan. 3, 1946, in Philadelphia, Penn. He was born into one of the great jazz families — his father was the saxophonist Jimmy Heath, his uncles were bassist Percy Heath and drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath – and raised by James Forman, a pianist. In the ’60s, after becoming a Black nationalist, he took the Swahili name “Mtume,” or “messenger.”

Mtume could be influential even when he wasn’t a part of the music. In 1970, he stopped by a Herbie Hancock soundcheck in Los Angeles; Tootie Heath was on drums. In front of the other band members, Mtume announced that he would be giving Heath a Swahili name. Hancock and company requested names as well. Mtume dubbed Hancock “Mwandishi” — Swahili for “composer” — and the pianist’s avant-funk group began going by that name as well. Things started to change for Hancock.

“We called each other by our Swahili names, and over time we started embracing other visible symbols of the black diaspora,” recalled Hancock in Possibilities, his autobiography from 2014. “I had never spent much time thinking about my African roots, but all of us became increasingly influenced by African culture, religion and music.”

Mtume had a similar experience with Davis. The trumpeter never took a new name, but he was happy to learn from his younger bandmate.

“Mtume was a freak for history, and I knew him from his father, so we used to talk a lot,” wrote Davis. “I’d tell him old stories and he’d tell me about things that had happened in African history, because he was really into that. Plus, he was an insomniac like me. So I could call him up at four in the morning because I knew he was going to be awake.”

“There will have to be an event. The political environment is what brings about the music. Society is a thermostat, your music is the thermometer. It tells you what the temperature is, it doesn’t set it. Right now, the thermostat for social change and seriousness is at a low level. Something will happen to make it heat up, and then the artists who will be the thermometers can tell you what the temperature is.”

More Stories

Hooverphonic live concert: passion, rhythm and movement, reawakening of old impressions. Videos

Among the group of musicians who came out of Miles Davis’ stable, it is Keith Jarrett who has achieved the greatest fame and is considered a true megastar: Videos, Photos

Live Review & Photo Gallery: Monsters of Blues – Rock – Scorpions, Queensryche, Savatage, Judas Priest at Allianz Parque, Brazil 2025