As an afternoon thunderstorm stalks the French Quarter, Charlie Gabriel sits in a crypt-like chamber off Preservation Hall’s private courtyard, focused on his rapidly diminishing prospects.

Across the courtyard, tourists file into the hall for the first of the evening’s four sets of traditional jazz. But the real action tonight is hidden from public view.

Chess, like music, God and cannabis, is a recurring theme for Charlie Gabriel. Backstage at the 2017 Bonnaroo Music Festival in Tennessee, he took on relative youngsters Chance the Rapper (“I beat him”) and Jon Batiste (“I think I beat him too”).

He’s not faring as well today, even as he moves quickly, decisively, like he doesn’t have time to waste.

“It depends on how hard Howard plays me,” he says. “If he puts those heavy moves on me, I have to scratch my head.”

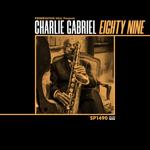

As Gabriel studies the chessboard in silence, Mary Cormaci, Preservation Hall’s digital media coordinator, slips into the room with a surprise: a hot-off-the-presses vinyl copy of his new album, “89.”

Sub Pop Records, the Seattle-based label that sparked the 1990s grunge movement with Nirvana and Soundgarden, released “89” on digital streaming platforms in February, then on LP, CD and cassette in July.

It is an intimate sonic snapshot taken in the twilight years of a still hip, still vital, much loved and respected elder statesman of New Orleans music, one of the last of his generation.

Cormaci hands the milestone album to Gabriel. He glances briefly at the cover, then sets it aside. Any emotional reaction will have to wait.

For now, he’s got a chess match to finish.

Besides, he recorded “89” months ago. And even at age 90 — especially at age 90 — Charlie Gabriel lives in the moment.

Music in his DNA

Sitting on his patio of the West End townhouse he shares with his second wife, Marsha, Gabriel reflected on a lifelong journey that began and, following an extended detour to Detroit, will likely end in New Orleans.

One of 11 children, he was blessed with the perfect jazz name — “Charlie,” as in Parker, Gabriel, as in the archangel. Music is in his DNA. His father, Martin Manuel “Manny” Gabriel, was a drummer who switched to clarinet and alto sax.

Growing up on North Galvez Street in the 6th Ward, Charlie heard clarinetist George Lewis, trombonist Jim Robinson and other early jazz pioneers accompanying funeral processions. Fluent on clarinet and able to read music, young Charlie filled in for local musicians off fighting World War II.

“I was 11, 12 years old, playing with all these older musicians — Kid Howell, Kid Sheik, Papa Celestin, Percy Humphrey, Willie Humphrey, whoever had a band that needed musicians,” Gabriel recalled.

His father took him to see his buddy Louis Armstrong. Armstrong rubbed young Charlie’s head and said, “Manny, I’m going to take this boy on the road.”

“He was kidding, but I thought he meant it for real,” Gabriel said. “But it made me feel good. I think that helped me as a young musician. That really inspired me.”

From New Orleans to Detroit

After World War II, Gabriel’s family moved to Detroit. Manny insisted they make annual trips back to New Orleans.

“My dad went to Detroit, but he never did leave New Orleans in his mind and thoughts,” Charlie said. “I kept the New Orleans connection through my father.”

As a teenager in Detroit, he joined vibraphonist Lionel Hampton’s band, sharing bandstands with a young Charles Mingus. In the 1960s, he toured with Aretha Franklin. He spent a decade with Cab Calloway’s drummer, J.C. Heard, and collaborated with trumpeter Doc Cheatham. He traveled the world; Singapore was a favorite destination.

In 2006, he got the call that brought him home.

‘This larger-than-life person’

After Hurricane Katrina scattered New Orleanians across the country, Preservation Hall faced a musician shortage. Drummer Shannon Powell suggested to Preservation Hall leader Ben Jaffe that he recruit Charlie Gabriel.

“He was almost like this larger-than-life person that everybody always talked about,” Jaffe said. “He knew the New Orleans repertoire and language, but he also knew all these other languages, like modern jazz and soul and R&B.”

For the next three years, Gabriel commuted between Detroit, New Orleans and the road. One reason he didn’t move right away: his burgeoning relationship with Marsha.

By the early 2000s, both Charlie and Marsha were widowed. He helped console her after her husband’s death.

“His kindness, his warmth, were too irresistible,” she said. “He is the most charming person you will ever meet, very kind, very spiritual. It was no big stretch to fall in love with Charlie.”

They married in Detroit in 2009, then officially moved to New Orleans. He’s been front and center at Preservation Hall ever since.

Game for anything

History is integral to the Preservation Hall brand. Musicians of Gabriel’s pedigree, versatility, mindset and age are essential.

Jaffe also pushes the Preservation Hall Jazz Band forward, adding talented young players and fostering collaborations with rock and pop stars. Gabriel is game for anything, from hanging out with the Foo Fighters to jamming with Chance the Rapper.

For younger musicians, he is a touchstone. Trombonist Craig Klein will call Gabriel if they haven’t seen each other in a while, “just to feel that energy, vibration and love. I can’t get enough Charlie G.”

Gabriel spends countless hours at Preservation Hall and at Jaffe’s former home near Frenchmen Street, which Jaffe converted into a residential-style recording studio. They drink coffee, play chess and make lots of music.

Gabriel is all over 2013’s “That’s It!,” the first album of all-original material in the band’s history.

When newsman Ted Koppel visited Preservation Hall in December to tape a “CBS Sunday Morning” segment, he interviewed Gabriel and Jaffe.

He also appeared alongside Snoop Dogg and New Orleans trumpeter Kermit Ruffins in the 2019 Netflix documentary “The Grass Is Greener,” hip-hop legend Fab 5 Freddy’s study of jazz and rap music’s association with pot and the devastating effect of American policymakers’ demonization of it.

Like Louis Armstrong, Gabriel is a dedicated cannabis consumer.

“The cats that smoked marijuana played better than those that didn’t,” he opines in “The Grass is Greener,” before inhaling on-camera. “I’ve been smoking for 70 years and really enjoyed it.”

For him, it is not necessarily recreational.

“Charlie’s position has always been that cannabis is something he uses as a ritual, as something that helps him get in a certain frame of mind,” Jaffe said. “It’s almost like lighting incense or saying a prayer for Charlie. It’s not a joking matter for him. It’s kind of like Bob Marley or Bunny Wailer. ”

“Willie got out his guitar, Charlie had his clarinet, and they played ‘Stardust,’” Jaffe recalled. “Just musicians getting to do what musicians love to do.”

Perhaps Gabriel and Nelson, the world’s most famous pot proponent, also smoked a little bit?

“More than a little bit,” Jaffe said. “It was a beautiful afternoon. They were like best buddies. Willie wanted to take him” on the road.

‘Full with love and music’

After a lifetime living out of suitcases and hotel rooms, Gabriel doesn’t go on the road much anymore, but still plays locally. COVID sidelined him for the 2022 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival’s first weekend, but he rebounded to front an Economy Hall Tent all-star band on the second Sunday.

He sat to play clarinet and sax, but stood to sing “Come With Me,” a song he wrote to help lure Marsha to New Orleans. Onstage, he radiated joy.

“When my horn’s in my mouth, I change to a different individual. I just become so full with love and music, I try to do everything at one time, everything that I have learned.

“But I know how to separate it now. You learn how to separate your music so it’s much more pleasing to the ear of other people. You can’t worry about showing off your skill as much as making them happy.”

Making other people happy explains in part why he recorded “89.”

“I just figured, me being as old as I am, it would be good. I’m at that age when you’re just lucky you’re living. If you get an opportunity to do something, to reflect upon your life, to produce something, you take advantage of it.

“And they want to get as much out of me as possible before I close my eyes.”

Melodies right out front

Jaffe, as the album’s producer, kept arrangements simple on “89.” Guitarist Joshua Starkman is the main accompanist, with Jaffe on upright bass. Percussion is minimal, so Gabriel’s clarinet, tenor sax and voice — he sings, sweetly, on three tracks — shine brightest.

“I had to use every ounce of patience and experience I had to get Charlie to do something this reflective, because he’s not someone to look back. It’s always, ‘What’s next down the road? What haven’t I done?’”

Six standards and two originals, clocking in just shy of 40 minutes, make up “89,” starting with “Memories of You,” a favorite of Gabriel’s father.

As a boy in the 1940s, Gabriel watched clarinetist Louis Cottrell Jr. showcase “Stardust” with Sidney Desvigne’s big band. He can close his eyes and remember the exact sound. “So it became part of who I am as a young man. Every time I play ‘Stardust,’ I think about Mr. Louis Cottrell.”

On the closing “I Get Jealous,” Gabriel sings and plays tenor over Starkman’s supple guitar runs while brushstrokes caress a snare drum.

Did he play the right notes on “89”?

He laughs. “I was lookin’ for ‘em. Sometimes you don’t find them. But you have to look to find them.”

In his element

The advantages of releasing “89” through a well-funded label like Sub Pop are apparent. The album’s cover, evoking classic Blue Note Records designs of the 1950s and ’60s, features a portrait of Gabriel by acclaimed photographer Danny Clinch. Clinch’s usual clients include the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Pearl Jam and Tim McGraw.

The official video for the song “I’m Confessin’,” shot in sumptuous black and white, depicts a dapper Gabriel cruising serenely in the back seat of a classic car and hanging with Jaffe and other musicians in the studio.

“I’ve been a blessed person, usually. I have no pain. I have no ailments. I’ve been healthy just about all my life.”

He’ll keep playing music as long as possible.

“I don’t know if I’m going to give it up or not. I give that a lot of thought. I wonder if I have anything more in me that I can bring to the universe.”

He holds up his hands.

“These fingers can only do so much. They’re getting old. I know myself. I cannot play like I played when I was 70 or 80. I can tell the difference.

“I just think I’m going to keep on playing until God tells me not to play anymore. And he will tell me.”

‘Live until you die’

God didn’t tell him to stop playing chess on that rainy afternoon at Preservation Hall. Gabriel, who adorned the September 2020 cover of Chess Life magazine, knew when it was time.

Lambert countered, “You taught me everything.”

The previous weekend, Gabriel beat Lambert three times. But today, Lambert turned the tables, winning twice.

“When you play Charlie, it’s a lose-lose,” he admitted. “I can’t stand losing to Charlie. But I really can’t stand winning against Charlie, either.”

Gabriel doesn’t dwell on defeat. After the chess board is packed away, he finally examined the translucent yellow vinyl of “89” and read the liner notes out loud.

“How about that, Charlie G?” he exclaimed, clearly pleased. “Not bad. I’m very proud of it.

“Everyone that touches this music does something to it. You bring fresh air into the music. Once it gets into the atmosphere, it stays.”

“A guy like myself, I’m not a baby — I’m 90 years old. I have to do what I have to do and hand it down to some others.

“I’m gonna be gone soon. I’m not afraid to die, so I don’t worry about it. But you have to live until you die. You have to keep doing what you do.”

That said, he was done for the day.

He would not join the other musicians inside Preservation Hall’s main room. His sweatpants and sneakers weren’t the proper attire. Also, he was exhausted after recording all day at Jaffe’s studio.

So he gathered up his horn and his pipes and stepped out into the storm, sharing an umbrella with Lambert, headed home.

But as he passed through Preservation Hall’s carriageway, he paused. The musicians were treating the tourists to “Shake That Thing,” a standard New Orleans party song.

More Stories

Interview with Micaela Martini: I really loved challenging myself in a different way in each song, Video, new CD cover, Photos

The 5 Worst Blues Albums of 2024: Album Covers

Cartoline: With the hope that this Kind of Miles will spark new curiosity and interest in the History of Jazz: Video, Photo