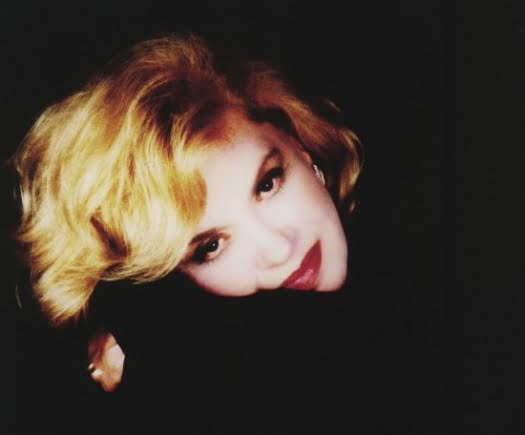

In April, Japan’s favorite jazz singer for more than 50 years returned for what she called her “sayonara” engagement. As Helen Merrill stepped onstage at the Blue Note Tokyo, her 1954 recording of “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To”—the standout of her now-iconic debut album with trumpeter Clifford Brown—filled the club to a roaring ovation. That track, which appeared in a Seiko commercial, had made the Manhattan-born blonde an idol of the Japanese. They were mesmerized by her foggy-sweet tone and stark minimalism, and by a delivery both confidential and mysterious. In Japan, she was called “the Sigh of New York.”

Back home, she hadn’t fared so well. Musicians embraced her, but her subtle approach and introverted stage presence were drowned out in noisy clubs and overshadowed by more flamboyant divas. “I remember once having seven dollars in the bank,” she says. “A lot of people didn’t believe in what I did.” Though painfully shy, Merrill followed her heart at all costs. She has lived a cinematic life, from sitting in with Charlie Parker to touring Italy with pianist Romano Mussolini, the son of Italy’s executed dictator, to moving to Japan and becoming the socialite wife of a newsman. “I was a very brave girl,” she says. “There’s a certain arrogance in youth. You don’t know how frightened you’re gonna get later on.”

So it was in 2009, when she lost her husband, the pop-jazz and Broadway arranger Torrie Zito. Yet on a recent evening in her home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Merrill, now 87, seemed ebullient and full of plans, while looking scarcely different today than she did on her early album covers. She speaks proudly of her son, songwriter Alan Merrill, who co-wrote “I Love Rock ’N Roll,” the No. 1 hit for Joan Jett & the Blackhearts. And she matter-of-factly recalls a childhood that was, at times, “horribly painful.”

The former Jelena Ana Milcetic is one of four daughters born to Croatian immigrants. Her father worked as a tugboat captain; her mother, Antoinette, was a Bible student. At home, Antoinette sang twelve-tone music from her birthplace, the island of Krk. Her big, intense voice “could make your hair stand up,” Merrill says. “From her I absorbed the fact that I could sing feelings.”

Antoinette’s were rooted in the pain of having lost her 6-year-old son, who fell from a fire escape. While Jelena was in grade school, mental illness sent her mother permanently to an institution. “She was brilliant—that was the awful part,” Merrill says. But to Antoinette, showbiz was evil. “If she had been at home,” the singer adds, “then Helen Merrill would never have existed.”

Merrill bought “race” records and loved folk singers like Burl Ives and Jean Ritchie. But jazz called out to her, “because it sounded honest to me, and it seemed like a place I could enter with my strange conception of music.” By her mid-teens the family had relocated to the Bronx, and Merrill went to Club 845 on Prospect Avenue and talked the promoter into letting her sing. The pianist was Bud Powell. “He started to play for me,” she recalls. “Then he stopped and looked around and gave me the biggest smile I ever got in my life. Singing with great musicians was my school. I’m not a teacher. I have to feed off what they’re playing.”

Though clearly sheltered—“She dressed like an old maid,” vibraphonist Terry Gibbs recalls—Merrill plunged into the New York bop scene, singing wherever she could. A lucky break occurred in 1952, when a grand pioneer of jazz piano, Earl Hines, hired both her and singer Etta Jones to tour with his orchestra. The two newcomers, one white and the other black, sat together on the stand, at a time when integrated bands were still controversial. One night the two young women were at the bar of a club listening to Charlie Parker, whom Merrill had met. Suddenly Parker announced, “Helen, come up here and show them how we sing in New York City!” She performed “I Cover the Waterfront” with Bird playing behind her—a public benediction from a musician she viewed as a god.

Merrill was then wedded to another gifted bebopper, the handsome but drug-addicted saxophonist and clarinetist Aaron Sachs, who played with Hines. “It should have been only a love affair,” she says. In the late ’50s they divorced; Merrill wound up supporting their son alone.

By that time, Hines trombonist Bennie Green and Quincy Jones had done her a life-changing favor. In 1954, both had raved about her to Bob Shad, the founder of EmArcy, Mercury Records’ jazz imprint. Solely on their say-so, Shad had signed her. Just before Christmas, she recorded Helen Merrill, produced and arranged by Jones. Amid a pack of bebop greats—including pianist Jimmy Jones, bassist Milt Hinton, bassist and cellist Oscar Pettiford and the rising Clifford Brown—Merrill seems like an island of restraint. She improvises sparingly, leaning more on her crushed-velvet timbre, held at a near-whisper, and phrasing that is full of intriguing tension and silence. Metronome’s critic noted her “completely different style.”

Merrill quickly grasped the possibilities of the LP, and in four more albums for Mercury/EmArcy she veered from standards to seek out folk songs, exotic show tunes and the work of such neglected composers as Alec Wilder. Everything was programmed to set a mood. Bill Evans loved her taste, and from Helen Merrill With Strings he drew two of his future trademarks, “You Won’t Forget Me” and “Beautiful Love.”

In 1956, she fought to record with Gil Evans, who was best known at the time for having arranged the Miles Davis landmark Birth of the Cool. “Gil took so much time in the studio; it had to be perfect for him. Bob said, ‘I can’t afford that!’” Merrill held her ground and wound up with a classic vocal album, Dream of You. She had enthused about Evans to Miles Davis, another of her fans. “I think I will call Gil and record with him again,” he answered. The next year, they made Miles Ahead.

But doors did not fling open for Merrill, who was “deathly afraid of audiences,” she says, and sang with closed eyes. “Clubs were noisy, and I became paranoid. I was not approachable. My objective was simply music, and how to protect myself from that horrible world out there. My pianist, Dick Katz, said that I had the biggest wall around me.”

Gigs were scarce; Merrill had to work in an art gallery and a boutique. In 1959 a failed love affair left her devastated, and when jazz critic Leonard Feather invited her to fly to England and sing on a BBC radio show he helped produce, Merrill scooped up Alan and went. She found that her album with Brown had traveled far. France wanted her; so did Belgium, Germany, Brazil and Italy. In 1960, Merrill was asked to sing in Japan. She stayed a month. The Japanese were touched by her obvious love for the country and her eagerness to return.

When Merrill finally went home in 1963, she had to start from scratch. Katz spent his own money to produce The Feeling Is Mutual, an album that teamed her with cornetist Thad Jones, guitarist Jim Hall, bassist Ron Carter and Katz. Eventually it was hailed as another masterwork of intimate vocal-jazz, but work in the U.S. remained hard to come by. By 1967 she was back in Japan, where she lived for several years with her second husband, Don Brydon, United Press International’s news supervisor for Asia.

Oddly, she performed little—“He didn’t like me to work in nightclubs”—but the recording studio remained her haven, a place where she experimented fearlessly. Well before Ray Charles delved into country music, Merrill recorded the album American Country Songs. On Parole e Musica (Words and Music), an actor recites Italian translations of American standards and Merrill sings them. She tackles protest songs on Helen Merrill Sings Folk, free jazz with bassist Gary Peacock’s trio on S’posin’ and rock on Helen Merrill Sings the Beatles. Affinity pairs her with the haunting tones of the Japanese bamboo flute. On Jelena Ana Milcetic a.k.a. Helen Merrill, she explores her Croatian roots. Along the way came albums with Teddy Wilson, John Lewis, Stan Getz and Ron Carter.

Most meaningful to her is Casa Forte, the Brazilian album she made in 1980 with the love of her life, Torrie Zito. Many more collaborations as well as marriage followed. Then Zito died of emphysema, and for years her will to sing faltered. Merrill had long said that she sang in the third person; if she sang in the first, the emotion would be too raw to bear. Playing a concert in Israel, Merrill sang “Don’t Explain,” a song from her first album. “A word, just one word,” she recalls, “and I started to cry. The word was ‘endures.’ ‘You know that I love you/And what love endures.’” She had to leave the stage.

But the public won’t let her retire, nor is she ready to. She would like to make an album in tribute to pianist-singer Jeri Southern, who showed her early on how to detach from the jazz-club din and escape into her own world. As for Japan, Merrill says, “I might go back for one more sayonara.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k73SL7QzTaM

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos