Steve Dalachinsky, a contemporary poet unrivaled in his dedication to the jazz avant-garde, not only as a gimlet-eyed observer but also as a prolific collaborator and performer, died early Monday morning at Southside Hospital on Long Island.

A steadfast presence on New York’s downtown scene — streetwise and pithy, sardonic but never jaded — Dalachinsky seemed to know everybody, and heard more live music than most. Many of his poems bear witness to some ephemeral magic on the bandstand, from the “long agos farewelled” of a Sheila Jordan-Steve Kuhn gig to the “screeching cohesions bowstrummed” of a concert by the Joe McPhee Quartet.

Within the avant-garde community, he was known as a discerning barometer. Jazz critic Francis Davis, who was born in the same year, advised his readers in The Atlantic “to keep an eye out for Steve Dalachinsky, a stream-of-consciousness poet and a loquacious advocate for his favorite players. His presence is a guarantee that on any given night you’re where the action is.”

Pianist Matthew Shipp, who first met Dalachinsky shortly after arriving in New York in 1983, remembered him on Monday morning in the present tense. “He’s very charming in one way,” Shipp said, “and in another way he’s so in-your-face and brutally honest. Personality-wise we just hit it off.” Their long creative partnership can be traced through a thicket of poems, performances and liner notes, as well as a book, Logos and Language: a Post-Jazz Metaphorical Dialogue.

Dalachinsky drew obvious inspiration from Beat poets like Jack Kerouac and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, but no less from Japanese haiku, e.e. cummings, Federico Garcia Lorca and other sources. And while jazz didn’t always provide the spark in his poetry, he acknowledged the depth of that connection; he was a permanent fixture at The Vision Festival, both as an artist and an audience member.

“Music is my main obsession and in avant-garde jazz just like in Beethoven’s late string quartets, the artists are always taking risks,” he said in a 2016 interview with AMFM Magazine. “Though many of my poems are fairly linear, they in part follow and try to become part of that rhythm, that movement, that risk.”

His work appeared in literary journals like The Evergreen Review, periodicals like The Brooklyn Rail, and chapbooks like Long Play E.P., for saxophonist Evan Parker. A decade ago, the RogueArt label published Reaching Into the Unknown: 1964-2009, a massive collection of jazz-respondent poems, with photographs by Jacques Bisceglia. A previous Dalachinsky collection called The Final Nite & Other Poems: The Complete Notes From a Charles Gayle Notebook 1987-2006 won the PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award.

Dalachinsky also performed his work on a number of albums — the first and most fateful being Incomplete Directions, released in 1999 on Knitting Factory Records, with accompaniment by the likes of Shipp, bassist William Parker and guitarists Vernon Reid and Thurston Moore. Positive response to the album led to the publication of A Superintendent’s Eyes, inspired by Dalachinsky’s experience as a super in a building on Spring Street.

Steven Donald Dalachinsky was born in Brooklyn on Sept. 29, 1946, and grew up in the Midwood neighborhood, later recalling his childhood as solidly working class. He was drawn early to the visual arts but soon switched over to poetry, inspired to no small degree by Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind.

He was 15 or 16 when he first heard Cecil Taylor, the sphinxlike icon of avant-garde pianism; he was walking past The Five Spot when the music pulled him in. Dalachinsky retold this story for an In Memoriam episode of Jazz Night in America last year. “The music went right inside me,” he said, “and my addiction to free jazz began.” As was often the case with Dalachinsky, affinity led to a long and lasting friendship. That warmth is evident in his 2009 chapbook The Mantis — and in this reading of “cecil taylor-derek bailey duo at tonic,” from last year.

Dalachinsky was a longtime SoHo resident, predating the neighborhood’s evolution into a phalanx of flagship boutiques. With his wife of 36 years, visual artist and fellow poet Yuko Otomo, he lived in an apartment stuffed with books, records, and art materials. In addition to Otomo, he is survived by a sister, Judy Orcinolo, and a nephew, Shaun Orcinolo.

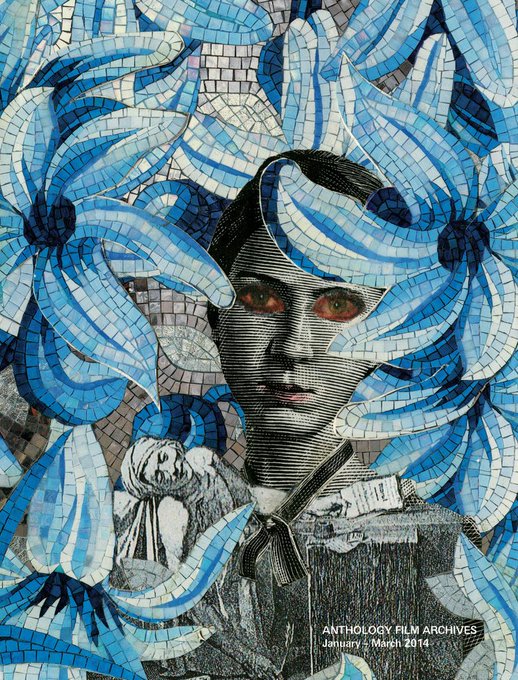

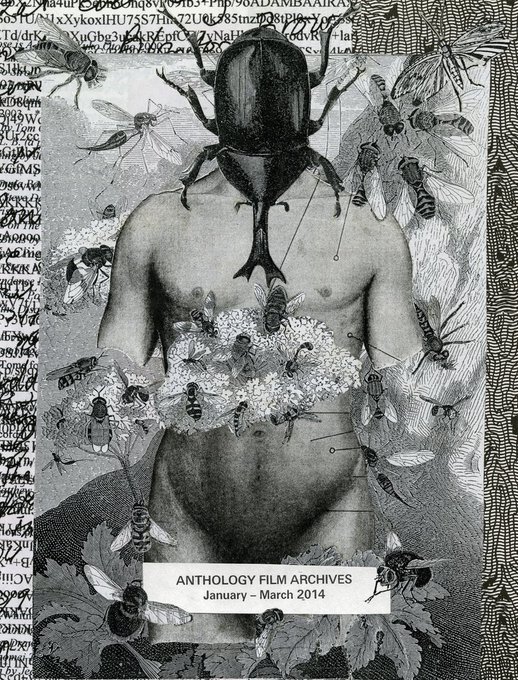

Along with his writerly calling, Dalachinsky was a serious collagist. His work was documented in collaborative practice and often in dialogue with his poems. Some of it became part of the fabric of New York, through local arts institutions.

On Monday, social media was awash with memorials to Dalachinsky — his tireless work, his generous friendship and most of all his vital presence. “There was no pretense with him,” said Shipp, speaking by phone. “He can’t really be replaced.”

More Stories

Shining gems from the sky Korea – Trilogy 3 – Chick Corea Trio: Video, Photos

Օne of South Africa’s most important jazz drummers – Louis Moholo – Bra Louis։ Video, Photos

Don Ellis: The Jazz anarchist – That crazy bastard broke the clock and it ain’t fixed yet: Videos, Photos