Jazz interview with jazz pianist and composer Greg Burk. An interview by email in writing.

JazzBluesNews.com: – First let’s start with where you grew up, and what got you interested in music?

Greg Burk: – I grew up in the USA in the state of Michigan in a town called Okemos. My father was an orchestral conductor and mother lyric opera singer so I hear classical music as a child and went to many rehearsals and concerts of Opera and classical repertoire. The study of classical music was not compatible with my innate personality as an improviser however so when I discovered jazz at age 16, it was such a relief to discover that there was a form of music where I could be myself.

JBN: – How did your sound evolve over time? What did you do to find and develop your sound?

GB: – My sound was formed by several important experiences. The first was my exposure to music in the house as a child. Second my studies at age 18 with Dr. Yusef Lateef and Archie Shepp at the U. of Mass. Afterwards I moved to Detroit and played on the scene there with living jazz masters like Larry Smith and Marcus Belgrave. When I decided to go back to school at New England Conservatory, I was already heavily rooted in the tradition of the jazz language. At NEC I was confronted with incredible personalities like Paul Bley, George Russell, Bob Moses, Danilo Perez….All of these musicians had a distinct interest and sound and that was when I began to focus more intensely on my sound. I believe that a player’s sound is formed through his/her life experience, encounter with other musicians and a deliberate choice as to what is more unique, personal and true in the music one makes. It is a choice to play what has meaning to the player, not simply a demonstration of what the player is capable of doing. This process is ongoing, with every note I play.

JBN: – What practice routine or exercise have you developed to maintain and improve your current musical ability especially pertaining to rhythm?

GB: – Great question! This is an area that interests me profoundly. I have a drum set and play it as often as I can. Rhythm is a physical manifestation of movement. If I play a beautiful chord and use the sustain pedal to hold it, the experience is more ethereal, cerebral perhaps. If I want to swing, or play in a groove, my body must respond and join the dance. Can this be practiced? Yes, but it really gets assimilated by playing with other rhythm masters, tuning into the drums, and playing drums too. As far as my other abilities, I try to refine my ear and listening powers as well. As for technical exercises, for many years I’ve tried to work out everything I learn in all keys. This has helped more than anything to resolve fingering and other technical issues.

JBN: – How to prevent disparate influences from coloring what you’re doing?

GB: – Well I actually do the opposite, disparate influences are always finding there way into my music, providing new ideas to develop and incorporate into my palate of colors and content. I can’t imagine making music in any other way. I can’t say everything I have to say on a song with chord changes, and the same applies for an open rubato improvisation. I think of it as moving between archetypes. I can understand the disorientation this might produce in a listener perhaps, but that is precisely what I am after, the experience of a journey through a spectrum of formal and emotional contexts.

JBN: – How do you prepare before your performances to help you maintain both spiritual and musical stamina?

GB: – Over the years I’ve developed ways of accessing what many call “the Zone” or what you refer to as spiritual and musical stamina. It starts with silence, breath and the surrender to sound, feeling and the ideas that are within grasp but not fixed. Clouds are constantly changing, organically, in subtle ways. They move but can appear stationary. They are made of water but also air, transparent but solid. These are the qualities of the mind of the improviser – an unforced, organic and light connection to the music inside the player, and to the band. That does not mean that there can’t be lightning and thunder in those clouds however! It is like the player is the earth, and the music are the clouds within the gravity of earth but floating above it. This requires a kind of acceptance of paradox – control and surrender – fixed and flexibility – guiding the direction but surrendering to change. This is the spiritual exercise. For several years I was in a group of the late John Tchicai called the Lunar Quartet. Enzo Carpentieri was also in the group. John was a very spiritual person and improviser, always starting from zero, totally aware of what was happening around him. He was a master of allowing the music to unfold in a natural and unforced way. I learned a great deal from that experience.

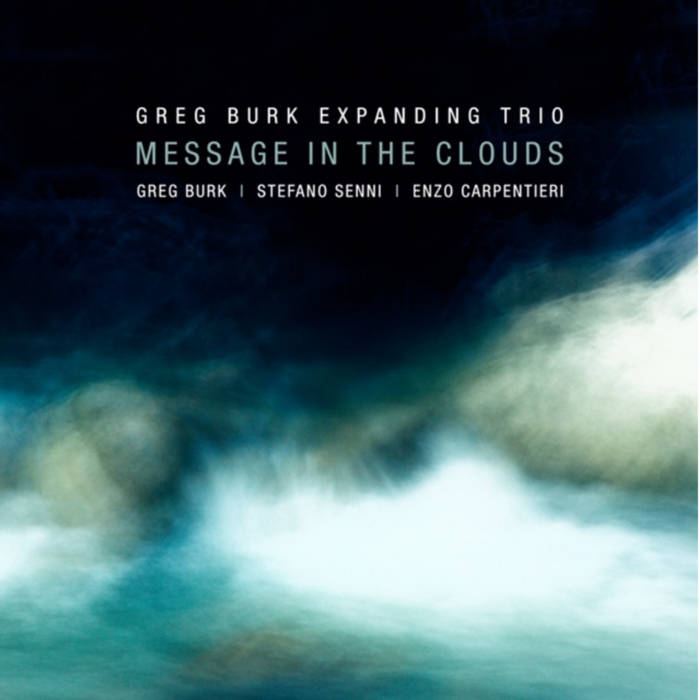

JBN: – What do you love most about your new album 2020: Greg Burk Expanding Trio – Message In The Clouds, how it was formed and what you are working on today.

GB: – I love the fact that this is an acoustic recording of this group that for years included the use of the Moog synthesizer. While I am fascinated by the Moog and its expressive possibilities, the band has more breath and subtlety in this purely acoustic setting. Both Enzo and Stefano have very personal sounds on their instruments. Touch is really something that identifies a musician and comes with years of experience. This new record captures these subtleties beautifully I think.

JBN: – Ism is culled from a variety of lives dates with various performers over the course of a few years. Did your sound evolve during that time? And how did you select the musicians who play on the album?

GB: – The trio is based in Italy where we performed in many clubs, festivals etc. and were able to forge our rapport and sound. We’ve also played around Europe and in Argentina. Our sound evolved as we evolved as a group and also as our repertoire changed. Like I mentioned earlier, a central part of the group’s concept is to move between paradigms, archetypes. This is tricky to do without sounding forces. While the context is changing, other elements remain intact. This takes time to develop. I selected Stefano and Enzo for this trio because they are the kind of musicians who can do this kind of movement while maintaining their sound, integrity and focus.

JBN: – What’s the balance in music between intellect and soul?

GB: – Music is made of relationships between pitches in time. The “What” and “When” of playing music depends greatly on the cultural context and tradition. In the case of jazz music, the “what” is very open. While there is a language of phrasing, vocabulary and syntax, jazz musicians have historically drawn from multiple sources of material that resonates with their curiosity and spirit. The “When” in jazz is specific in that there is a language of swing and group playing that must be assimilated, even if it is later abandoned. This is my opinion. The soulful part of playing this music comes from the “How” and especially the “Why”. How something is played is the interpretation that the player gives the notes or the “What”. Sound, accent, inflection, breath, dynamics are the details that make this music ultimately un-transcribeabe and powerful. The “Why” of music is the ultimate question and the more spiritual question if you will. This is more subjective but also objectively defined as in the overwhelming spiritual power of the music of Coltrane. That kind of emotional intensity, the fearless abandon to in the moment burning of feeling and thought is among the most rare and powerful of all recorded music, in my mind. The balance need not be so extreme however for a music to be spiritual, to express joy, love, sadness and compassion.

JBN: – There’s a two-way relationship between audience and artist; you’re okay with giving the people what they want?

GB: – It’s hard to say what an audience wants. Certainly different listeners have different requests and expectations from the performers. When we talk about jazz in a general way we’re talking about groove, lively solos, memorable tunes, group interplay and sound. These are all satisfying in and of themselves when done well. But is that enough? What about concept, provocation and identity? These are more complicated lines to draw as the performer risks losing the audience as he/she pursues a highly personal interest or concept. Herein lies artistry. Can the performer satisfy the universal desires listeners for groove, melody, narrative etc. while challenging them to accept a personal vision, original composition or concept? Paul Bley is a perfect model of this artistry to my mind. Because he was forged by the strenuous challenges of the tradition in the 50s and 60s, his more experimental music, as far as it may have stretched the listener into new areas, never completely abandoned melody, phrase and swing. Some listeners want an easier experience and others a more challenging one. This is a balance that each artist must work out. If the music is sincere and done at a high level, there will always an audience.

JBN: – Please any memories from gigs, jams, open acts and studio sessions which you’d like to share with us?

GB: – Once when I was living in Detroit, Eddie Harris came into the club where I was playing. He wanted to play “Dahoud” the Clifford Brown composition. I didn’t know it very well so he came over to the piano and played a solo with two fingers, his pointer finger in his right hand and his left hand pointer finger. The solo was simple but made perfect sense in every way, and was swinging like crazy. It really left an impression on me!!!

JBN: – How can we get young people interested in jazz when most of the standard tunes are half a century old?

GB: – Repertoire is part of the issue, although I’m not sure many fans in the 70s and 80s necessarily knew the broadway versions of Standards. Some musicians now are moving to electronic instruments, simpler chord progressions, binary rhythms with back beat etc. The number of young people studying jazz today is astronomical. This gives me faith in the future of this music. While I am attached to the tradition, and the way it transforms a talented young person into a fully formed musician, I also understand that art, expression, languages change. Evolution is not the way I think of it, but actuality. Times are fundamentally different now so music will reflect that. Jazz is a participators sport, equally for the listener as the player, even if the listener is just tapping their foot or daydreaming while listening. The risk is that people become too passive to enjoy and experience the power and joy of listening as participators.

JBN: – John Coltrane said that music was his spirit. How do you understand the spirit and the meaning of life?

GB: – Whoa! Still working all of this out. Spirituality is by its nature something impossible to write about. I can tell you that a full moon is white, bright and beautiful but until you see it then the words have no real meaning. Coltrane was an innovator in many senses of the word and the spiritual element was, in my mind, the intensity of thought, dedication and emotion in his music. The boundaries he broke in this sense changed the world forever. There are other spiritual teachers in music today. One is Tisziji Munoz. For me the meaning is to stay on the path, be dedicated, be real and to bring to the music something that is meaningful to me. While this may sound selfish, if the music is only an elegant exposition of knowledge and ability, then the player has missed a great opportunity.

JBN: – If you could change one thing in the musical world and it would become a reality, what would that be?

GB: – There would be a place to hear live music on every street, on every night of the week.

JBN: – Who do you find yourself listening to these days?

GB: – I’ve been listening to the music of my friends and colleagues a lot lately. I also listen to my favorites like Coltrane, Monk, Joe Henderson, Paul Bley, Jarrett… I went through a Glen Gould phase recently too. Because I’m working on new recordings I inevitably listen to those a lot too.

JBN: – What is the message you choose to bring through your music?

GB: – I hope the message I’m projecting is sincerity, curiosity, integrity and especially gratitude. This is the amazing gift of music. It can heal us and transform us is subtle ways. It’s power is something that we only partly understand. I try to reflect the gratitude I feel to have contact with this powerful medium, to have the freedom and tools to explore my mind and spirit through this medium. Jazz is unique in this way. When I think of the great suffering of African Americans in the USA and the tremendous joy in the music of say Louis Armstrong or Earl Hines or Monk, it is a lesson for all of us. I want to bring that same sense of joy, gratitude and commitment to my music.

JBN: – Let’s take a trip with a time machine, so where and why would you really wanna go?

GB: – To the future, maybe 200 years from now so I can see how humans will finally awake from their adolescence and become more compassionate, rational, intelligent and just.

JBN: – So putting that all together, how are you able to harness that now?

GB: – It’s a work in progress!!!

Interview by Simon Sargsyan

More Stories

Interview with Janis Siegel of The Manhattan Transfer: Jazz, being a more refined, interpreted form of music

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos