The pianist’s “Retrospect In Retirement Of Delay” is a historic outpouring of musical imagination. The pianist and composer Hasaan Ibn Ali is an unduly elusive presence in the history of jazz. His first album, with a trio, was released in 1965; his second, with a quartet, recorded later that year, wasn’t released until early in 2021.

Both showed him to be a distinctive and original musician, but what they offered, above all, was the sound of possibility, of unfulfilled potential. The new release of Hasaan’s “Retrospect In Retirement Of Delay: The Solo Recordings” (Omnivore Recordings), which features him in privately recorded performances from 1962 to 1965, reveals his profundity, his overwhelming power, his mighty virtuosity. It does more than put him on the map of jazz history—it expands the map to include the vast expanse of his musical achievement.

Hasaan was something of a legend in Philadelphia, but played little elsewhere. His solo recordings were made by David Shrier and Alan Sukoenig, two jazz-aficionado undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania who’d befriended him. He visited them at the university and allowed them to record him playing pianos in dormitory and student-union lounges as well as in Shrier’s apartment and in a New York apartment to which Hasaan summoned Sukoenig and his tape recorder. Those circumstances sound ripe for music of modest intimacy; instead, what Hasaan played is torrential. (The sense of short-term urgency is reflected in the amazing fact that nine of the tracks, including the four longest of them, were all recorded on the same day—October 25, 1964—at three different venues.) The album’s twenty piano performances emerge like contents under pressure, like furies of musical imagination that had been building up within Hasaan for a long time, as if he knew that he was playing on the biggest stage of all: the stage of eternity.

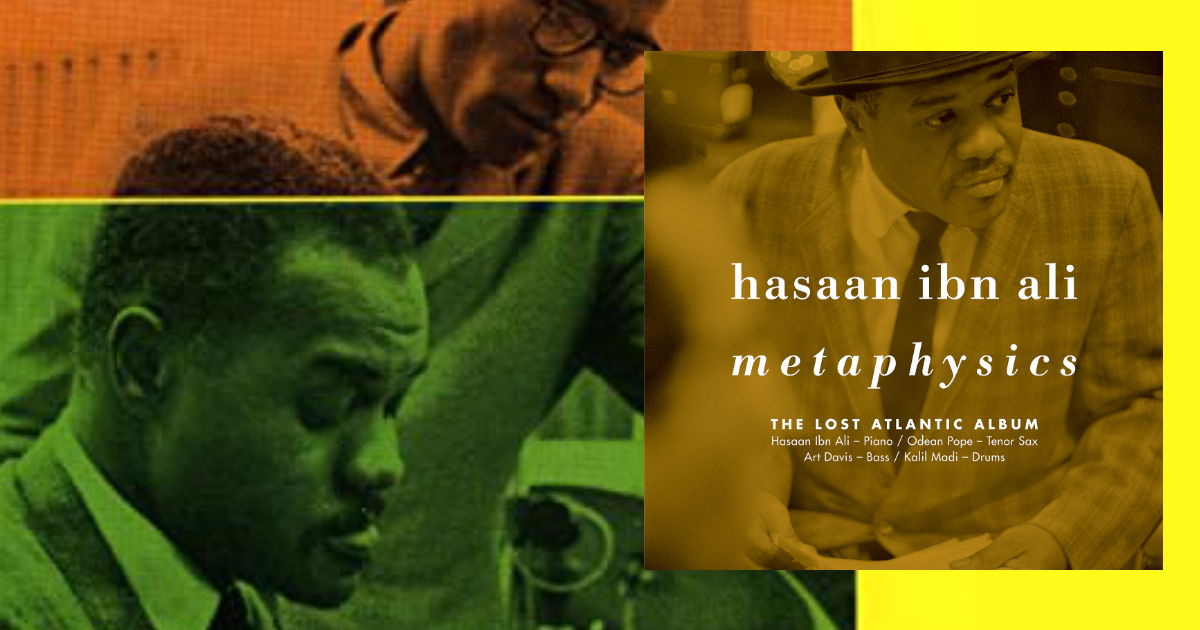

Born in Philadelphia in 1931, and performing originally as William Langford, a modified version of his given name (his parents spelled the family name “Lankford”), Hasaan gigged there in the late forties and early fifties with the city’s rising young musicians, including John Coltrane, four years his senior, who is said to have studied with Hasaan. (Later, Hasaan reportedly claimed that Coltrane had stolen his ideas.) In other words, as a teen-ager Hasaan was already an artist among artists and, in his early twenties, was a recognized innovator. His approach to music was so unusual that, despite the place of honor he won among the city’s greats (including Philly Joe Jones, Benny Golson, Jimmy Heath, and the brothers Bill and Kenny Barron), his professional and commercial opportunities were limited. Hasaan lived his entire life in Philadelphia and did much of his performing, according to the saxophonist Odean Pope, in private: “At night, after he got dressed, there were three or four houses he would visit, where they had pianos. The people would serve him coffee or cake, give him a few cigarettes or maybe a couple of dollars from time to time.” In the early sixties, at a time when his musical peers were already famous and already amply recorded, Hasaan—in his thirties—was being recorded by students with amateur equipment. (His first album, “The Max Roach Trio Featuring the Legendary Hasaan,” was recorded in December, 1964; the long-unissued quartet album, “Metaphysics,” is also an Omnivore Recordings release.)

What’s most miraculous about the preservation of Hasaan’s solo performances and the survival of the tapes is the artistry displayed in the performances themselves. The astonishments of the new album begin with the very first notes of the first track, the standard “Falling In Love With Love,” which Hasaan begins with a jaunty, tango-like bass riff that recurs throughout like a one-hand big-band accompaniment. That percussive figure maintains a rhythmic foundation that prompts Hasaan to cut loose with crystalline, florid barrages of high notes in shifting forms and meters that cascade and swirl and swarm in ever more daringly chromatic and far-reaching harmonies. Hasaan had worked out, a decade earlier, a so-called system by which he’d use substitute chords that both vastly varied yet recognizably retained the composition’s original framework. This is what Coltrane is believed to have derived from their time together, and the wild profusion of notes unleashed by Hasaan’s right hand, like a skyful of brilliant stars scattered by the fistful, is indeed reminiscent of what the critic Ira Gitler famously termed Coltrane’s “sheets of sound.”

With tacit but manifest audacity, Hasaan appears to be self-consciously claiming his place in the history of jazz, picking up gauntlets thrown by the greats—playing a thirteen-minute version of “Body and Soul,” which Coleman Hawkins made the culminating solo of the swing era in 1939; a ten-minute version of “Cherokee,” the tune that first brought Charlie Parker fame and that is identified with the birth of bebop; selections from Miles Davis’s repertory (“On Green Dolphin Street” and “It Could Happen to You”); and Thelonious Monk’s “Off Minor.” Hasaan introduces “Body and Soul” with a new countermelody of his own that helps him break up the familiar tune so surprisingly that, twenty seconds in, the interpretation is already historic. He turns the Rodgers and Hart waltz “Lover” into a fifteen-minute up-tempo romp with a syncopation of its melody that becomes the dominant stomping figure of his bass line while his right hand throws off barrages of rapid-fire scintillations that subdivides measures into infinitesimals. In a thirteen-minute expatiation on the harmonically complex ballad “It Could Happen to You,” Hasaan turns the clichés of melodramatic tremolos into a percussively thunderous rumble; amid shimmering storms of high notes, he returns to the melody with a sudden stop-and-fragment-and-restart that’s both breathtakingly dramatic and side-shakingly funny.

It seems to me no mere happenstance that Hasaan’s mighty, mural-like musical self-portrait in real time comes in the form of solo piano. In his trio and quartet recordings, the accompaniment of bass and drums seems to inhibit him, to channel his solos into forms that would accommodate the musicians’ interpretations (however splendid) of the essentials of rhythm and harmony that he generated for himself, copiously and ingeniously, with his own two hands. His musical concept comes off as comprehensive, mercurial, eruptive—not that of a chamber musician but that of a one-person orchestra. He provides more than the intimate image of a musical mind at work; he conveys the galvanic sense of a heroically physical musical battle against time.

Hasaan’s career went from decrescendo to catastrophe. Disheartened by his truncated recording career, Sukoenig writes in his richly informative liner notes, Hasaan became withdrawn. He was living with his parents when their house caught fire, killing his mother, leaving his father incapacitated, consuming Hasaan’s compositions, and leaving him mentally debilitated. He was housed in a group home, was in drug treatment, had a devastating stroke, and died in 1980, at the age of forty-nine. In a 1978 interview that Sukoenig quotes, Roach (who died in 2007) said that he made home recordings of Hasaan when the pianist visited him: “I have hours of him playing solo piano that’s unbelievable.” Sukoenig says, however, that no other recordings, commercial or private, of Hasaan have surfaced. In any case, “Retrospect In Retirement Of Delay” proves that Hasaan was no might-have-been—he was, he is among the handful of greats.

More Stories

CD review: George Benson – Dreams Do Come True: When George Benson Meets Robert Farnon – 2024: Video, CD cover

The band was tight as ever. The Warren Haynes Band cuts loose: Video, Photos

Interview with Alvin Queen: Feeling Good – I heard these tunes played by … Video, new CD cover, Photos